Blessed John Soreth was a Carmelite of the fifteenth century who wrote an important commentary on the rule of that order. In it, he gives what I think is a good synthesis of a lot of pre-modern thought on Christian contemplation. I owe my knowledge of this summary to Saint Titus Brandsma:

This treatment of contemplation [given by Blessed John Soreth], to which the life in the cell must be primarily devoted, is especially noteworthy. He distinguishes a threefold meditation and calls special attention to all three forms.

In the first place, he proposes the admiration of nature, then the reading of the Sacred Scriptures and finally an introspection of our own lives. These three kinds of contemplation he does not regard as necessarily connected but rather as subjects deserving a separate treatment in various hours of meditation. Only now and then they will have to be regarded in their relation to each other.[1]

This is, as I said, I think very indicative of pre-modern sensibilities about prayer.

Three loci of contemplation

The focal points from which contemplation can spring are, in this pre-modern scheme, three:

- admiration of nature

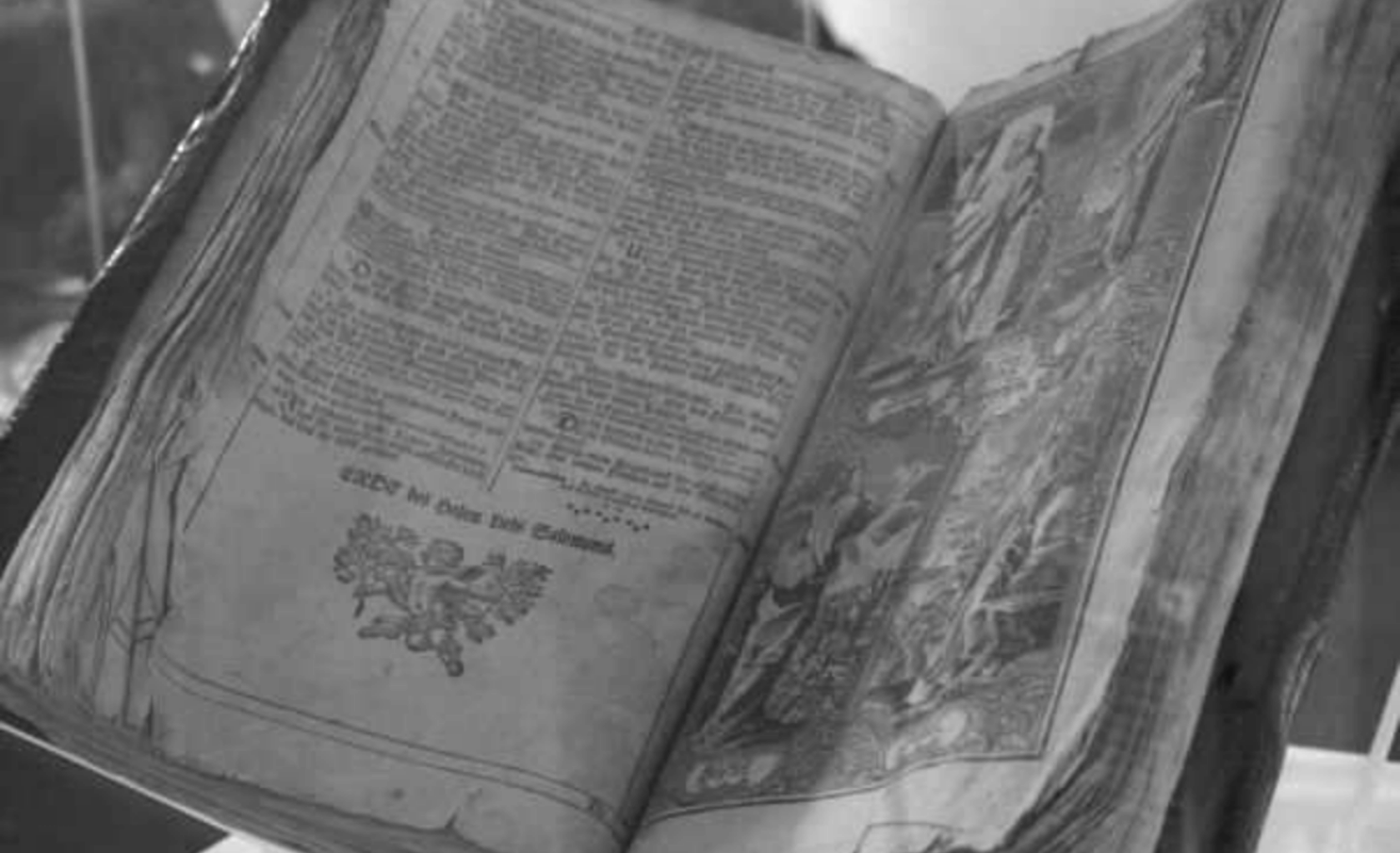

- reading of the Bible (lectio divina)

- introspection of our own lives

It is from these starting points that we are led into a unified affective and intellectual regard for God. Titus Brandsma thinks that such a balance is important, and he highlights it repeatedly throughout his treatment of Carmelite spirituality.[2] We may safely assume that this is the moment that results from the more laborious, piecemeal consideration of nature, the Bible, and our own lives.

The list compares interestingly with more contemporary ones, such as that which one can extract from Pope Francis’ teaching:

- contemplation of the beauty of God in the Divinity Itself

- starting from gratitude for God’s creation

- starting from another source (e.g., lectio divina)

- contemplation of the beauty of God in Christ

- in historical Palestine or in Heaven (via, e.g., lectio divina)

- spread out in time and space in the age of the People of God

Characteristic of modern developments in consideration of prayer is the multiplication of sources of consideration of the Divinity Itself and of Christ’s Humanity; we could still read the Bible, but frank avowal of other devotions become more commonplace in the modern period. Also characteristic of modern developments is the expansion from “providence in my own personal life story” to “providence in the whole of the People of God, not excluding myself, but considering others and the social movement of the world under the inspiration of the Spirit.” In both cases, we have a development and an expansion of what should already be implicit in the older pre-modern formulations. But the essential nugget remains the same.

The one term that hasn’t expanded or changed at all, curiously enough, is admiration for or grateful contemplation of the natural world, of God’s creation. In that sense, if you were to talk to a (learned) Christian from a half-millennium ago about contemplation, the place where you would find the most conceptual and explicatory overlap would be prayer that starts from considering the natural world. There is more clear continuity in that department that others, fewer changes and developments. It is thus apparent that those who would disparage what Pope Francis has called “the eighth work of mercy” are the ones who are the least traditional.

Separate subjects?

Where I think John Soreth needs a little pick-me-up, however, is in regards to the way that his three loci of contemplation constitute “subjects deserving a separate treatment in various hours of meditation. Only now and then they will have to be regarded in their relation to each other.” This, I think, is something that has been superseded.

Pope Francis is emphatically clear, for example, that of the the cry of the poor emerges especially when there is the cry of the earth (Laudato Si’ 49; Querida Amazonia 8, 52). They are note entirely separate subjects of meditation to be turned into contemplation. Rather, they are interrelated. Similarly, Pope Francis uses the contemplation that Jesus had of his Father’s creation as a lynchpin for all his social thought of the cry of the poor and the cry of the earth in the ecological and climate crises (e.g., a contemplative reading of Laudate Deum).

What is truer for us today is the fluidity of the contemplative loci. Perhaps this is driven by our greater appreciation that “everything is connected” (LS 16, 91–92, 111, 117, 120, 137–162, 240). Whatever the cause, it is a fact of life today. We can’t go back to the separability of the meditative starting points.

Continuity and development

This short little post, then, has one simple aim: to show that, in the tradition of Christian prayer, which we might be tempted to regard as the most static of the traditions of the Church, there is both continuity and development. What is known and loved is handed on, but the act of doing so in novel circumstances produces elucidations and remarkably more consistency and interrelated understanding that was had by previous generations. Handed on, developed, not corrupted.

[1] Titus Brandsma, “Carmelite Mysticism: Historical Sketches” (1936), in Mysticism: Fundamentals and Characteristic Features, ed. Elisabeth Hense and Joseph Chalmers (Rome: Edizioni Carmelitane, 2023), 245–325 (here, 287).

[2] Ibid., 254–256, 272; “The Spirituality of the Carmelites before the Reform of St Teresa and some Developments of the Calced Tradition Thereafter” (1937), in ibid., 326–351 (here, 340–341).