In issuing an invitation to “our God-given aesthetic and contemplative sense” (Querida Amazonia 56), Pope Francis seems to suggest that there’s one united sense that has these two operations that we call “taking in beauty” and “contemplating.”

The place where this is most apparent is when the pope discusses nature and ecology. The invitation that we first saw issued boils down, more or less, to the following: “Beauty is the entryway to ecological awareness.”[1] When we become aware, then we can respond. Nobody appreciates the intrinsic beauty of something and then right away starts to destroy it or use it as a mere means to an end. We’re changed by the experience. So are our actions.

Of course, the way that we appreciate beauty and contemplate when it comes to ecological nature is different from when it comes to God or human beings. But the central idea is the same. Appreciating their intrinsic worth, their beauty, we don’t turn around on the spot and treat them as just a way to get something we want. The experience of their worth and beauty affects us.

This is pretty reasonable. It’s reasonable in that way that exceeds rationalizing. Because rationalizing is just a way of using things to achieve an end, whereas this appreciation of beauty is “beyond reasonable” because it re-adjusts our ends.

The question, though, is: Why did Pope Francis decide to associate beauty and contemplation like this?

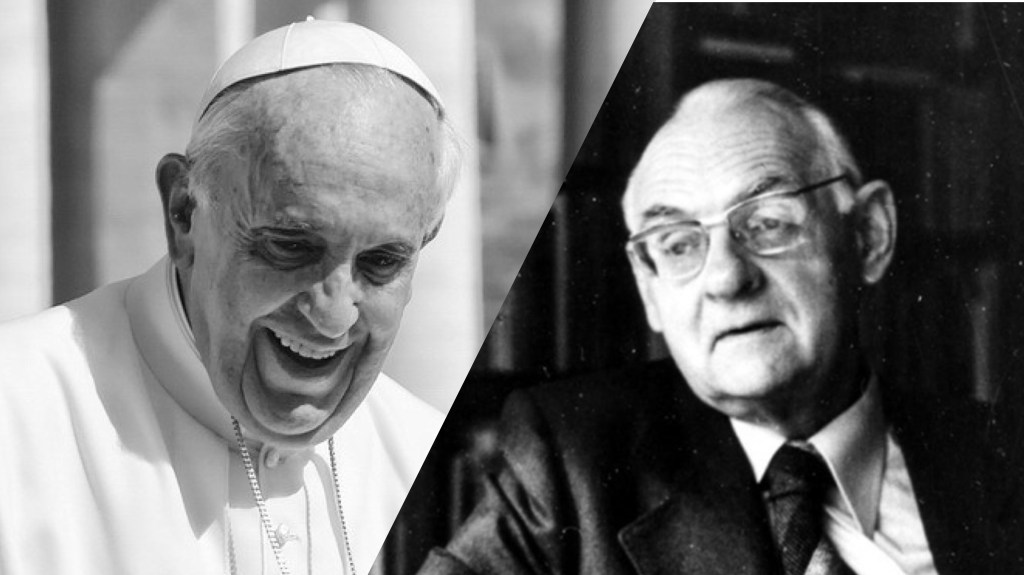

Pope Francis’ own testimony: von Balthasar

We’re talking about aesthetics/beauty. I think it’s pretty clear that, at the surface of Pope Francis’ reading here is Hans Urs von Balthasar. He’s a pretty important guy for the pope, at least in this century. Recently, Jorge Mario Bergoglio has spent a lot of time in the Swiss theologian’s company.

You can tell this from his own reactions. For example, when a conference was held in the English-speaking world on the influences and thinking of Pope Francis, the papers were published as a book.[2] When that book was published, the Holy Father offered his own “papal foreword.” The first line of this speaks of Hans Urs von Balthasar.[3] Part of me suspects this is because the volume didn’t dedicate enough space to von Balthasar’s influence. He has to share a chapter with another author, and the scope of their combined influence extends to all the popes since Vatican II, not just Francis. This was hardly the attention due to such an important figure.

More particularly, Pope Francis has told Massimo Borghesi: “Regarding Balthasar… His aesthetic impressed me a lot.”[4] That’s pretty straightforward. The number of times beauty, Pope Francis, and Hans Urs von Balthasar appear together in Borghesi’s book is pretty telling, too.[5] I think we can take the connection between Pope Francis and von Balthasar as well established.

Beauty, truth, goodness

The main point with von Balthasar is, as far as Pope Francis is concerned, the importance of remembering beauty. We can’t treat the goodness we love, and the truth we seek, without thinking too of the beauty that attracts us and holds us captive. As Guzmán Carriquiry Lecour notes in the foreword to Borghesi’s book:

We also see in his [Pope Francis’] more recent thought the development of the category of beauty and its unity with the good and the true. It is a development that owes much to his reading of the great theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar.[6]

In scholastic terminology, beauty is a “transcendental,” just like truth and goodness. Don’t forget it!

Now, you can search the Vatican website for instances where Pope Francis mentions beauty, truth, and goodness together. You’ll find a lot. I choose here one, not quite at random, but not with a lot of thought, either:

Beauty brings us to God. And a truthful witness brings us to God, because God is also truth. He is beauty and he is truth. A witness intended to help others is good, it makes us good, because God is goodness. It brings us to God. All that is good, all that is true and all that is beautiful brings us to God. Because God is good, God is beauty, God is truth.[7]

We can see how the pope keeps these three together: beauty, goodness, truth. They appear together. They lead to the same place.

But if we separate truth, goodness, and beauty, things will go awry. To take truth without goodness is just a theory or an ideology. To take goodness without truth is sentimentalism or aestheticism. To not realize that beauty is there when the two are there together—we’d have to close our hearts to what it is that makes something attractive! We need to always present—and live—these three together. That’s the only way to avoid mere whims and ideology.

It’s an important lesson. No wonder Pope Francis hammers on about it.

A bit further in the background: Methol Ferré

Pope Francis himself, his intellectual biographer Massimo Borghesi, and his friend Guzmán Carriquiry Lecour all say that it is from Hans Urs von Balthasar that this serious reflection on aesthetics/beauty takes shape. But in Borghesi’s book, there’s another important figure, whom Jorge Mario Bergoglio studied earlier, who said much the same thing.

Consider this passage from the Uruguayan philosopher Alberto Methol Ferré:

Beauty maintains an original link with truth and goodness; it is inseparable from them both. When it is torn off, it decays into an aestheticism for intellectuals or gives rise to a vitalism that pursues pleasure at all costs. In both cases it becomes, in the end, an accomplice of injustice.[8]

It’s because we keep these three together that we avoid making any interest in beauty into either a vitalism/sentimentalism, focused on whatever it happens to be that we want, or an “aestheticism,” focused on whatever it happens to be that we treat as an elite subject of aesthetic appreciation.

Pope Francis himself warns against both the errors Methol highlights. The danger of desires runs through Laudato Si’, among other places; we have to curb desires and consumption. Meanwhile, aestheticism is dealt with when the pope speaks of an “aesthetic relativism which would downplay the inseparable bond between truth, goodness and beauty” (Evangelii Gaudium 166). This “aesthetic relativism” seems to be exactly what Methol means by “aestheticism.”

Personally, I find Methol’s teaching incredibly similar to what Pope Francis is supposed to have drawn from von Balthasar. It might be less fashionable to prefer Methol. He’s South American. He’s a self-described “wild” or “rogue” Thomist. He’s not well known in European circles. But Pope Francis read him assiduously at an earlier time.[9]

At any rate, the idea is the same. If we want to say it’s von Balthasar at the surface, that’s fine. But to be fair, Methol Ferré must be in there somewhere, just a little deeper below the surface.

Explicitly in the context of contemplation

Now, for Pope Francis, the interesting point is the linking of this very thought to contemplation. Here’s a very informative passage from his time as cardinal archbishop of Buenos Aires:

Only those who show themselves fascinated by beauty can introduce their students to contemplation. Only those who believe in the truth that they teach can ask for true interpretations. Only those who believe in the good… can aspire to shape the hearts of those entrusted to them. The encounter with beauty, with the good, and with truth fills a person and produces a certain ecstasy. What fascinates us transports and transforms us. The truth that we encounter—or rather, that comes to meet us—makes us free.[10]

The words that I’ve italicized here show the connections. Beauty and contemplation go together. If you can’t appreciate the beauty of something, you can’t contemplate it. At the same time, beauty doesn’t go by itself. It’s the companion of truth and goodness.

The point about the threefold friendship beauty–truth–goodness, we know, comes from Hans Urs von Balthasar (and Methol Ferré). But to the best of my knowledge, the addition of contemplation to this triad is not something that he takes from either of them.

For example, I’ve read Prayer by von Balthasar.[11] This is actually a book, not just about prayer, but about contemplative prayer. It is divided into three sections: “the act of contemplation,” “the object of contemplation,” “the tensions of contemplation.”

Yet nowhere in von Balthasar’s book is beauty so linked to contemplation as it is for Pope Francis. The idea of beauty occurs here and there.[12] But it is simply not an underlying theme. When the adjective “aesthetic” is used, it seems to me to reflect what Pope Francis and Methol Ferré mean by an “aesthetic relativism” or an “aestheticism” for intellectuals. Certainly, the entire experience of Christian contemplation is not framed, as it is for Pope Francis, as an outreach of the ability to take in the beauty of some reality. When von Balthasar discourses on contemplative prayer, he uses different frameworks and organizing notions.

What we have and what we’re missing

Even though we are repeatedly told that Pope Francis admires von Balthasar’s aesthetic thought, what we have is really two distinct elements, two separate intuitions:

- Beauty is part of a triad of transcendentals, along with truth and goodness; when we know something true and are drawn to its goodness, we (can) appreciate its beauty

- Contemplation arises from the same “sense” as the one that goes about appreciating beauty

The first element can be sourced in Hans Urs von Balthasar, as Pope Francis himself has told us, or as the biographer/historian Massimo Borghesi shows, or as the pope’s friend Guzmán Carriquiry Lecour asserts. It can also be traced to Holy Father’s familiarity with the (unusual) Thomist philosopher Alberto Methol Ferré.

The second element is something else. We can’t explain it in reference to von Balthasar, for whom “aesthetic” in the same breath as “contemplation” or “prayer” jumps immediately into “aestheticism” for an elite.

This second element, then, comes from somewhere else. There is something else propelling Papa Francesco to say that, hey, if I really think that beauty is as von Balthasar’s aesthetic makes it out to be… if beauty relies on these two dimensions of truth and goodness… if this is what appreciating beauty entails… then, by golly, contemplation in a Christian sense is actually an appreciation of beauty. It’s an aesthetic experience—not in the sense of some elitist, snobbish, narrowed-down field of interest, of course. God forbid aestheticism! But insofar as we genuinely take in, rest in, and act to preserve and highlight beauty, that can be a contemplative experience.

This second intuition says: Because of what beauty is, you can’t tear beauty and contemplation apart. Whether we mean the beauty of ecological nature, of human persons, or of the Trinitarian persons by grace, the same human or psychological dimensions are in play. Our single “God-given aesthetic and contemplative sense” is engaged.

I think we can trace this second big intuition to something said by Saint Charles de Foucauld and read by young Jorge in the many books of René Voillaume. But that’s a whole other blog post yet to come…

[1] Pope Francis in conversation with Austen Ivereigh, Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), 30.

[2] Discovering Pope Francis: The Roots of Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Thinking, eds. Brian Y. Lee, Thomas L. Knoebel (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2019).

[3] Ibid., xiii.

[4] Massimo Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey, trans. Barry Hudock (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2018), 275.

[5] Ibid., 225–227, 244–253, 256, 286 (at least).

[6] Ibid., xiii.

[7] Pope Francis, “Prayer Vigil for the Festival of Families” (B. Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia; September 26, 2015), which can be read here.

[8] Alberto Methol Ferré and Alver Metalli, Il Papa e il filosofo (Sienna: Cantagalli, 2014), 157, in Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis, 185.

[9] Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis, 85–99.

[10] Jorge Mario Bergoglio, “Insegniamo a non temere la ricerca della verità (2008), in Bergoglio–Francis, Nei tuoi occhi è la mia parola (Milan: Rizzoli, 2016), 635–636, trans. Borghesi, The Mind of Pope Francis, 247.

[11] Hans Urs von Balthasar, Prayer, trans. Graham Harrison (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1986).

[12] Five times in total, I think, for “beauty” and “beautiful,” and not all of them positive. A further four or so times for “aesthetic,” and all of them negative or diversionary.