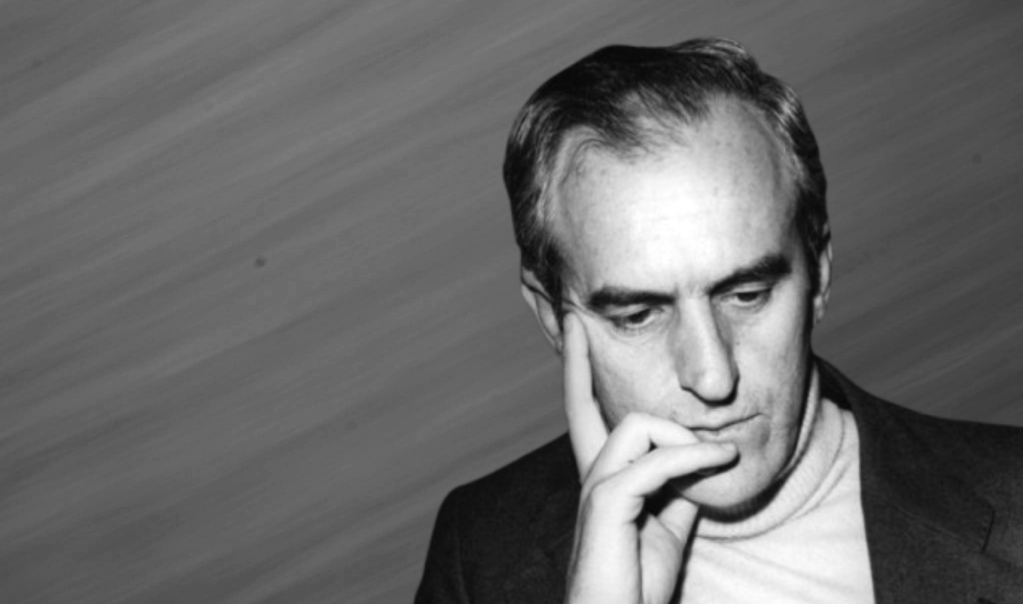

The central place given to the contemplation of the Lord of history in last week’s apostolic exhortation has inspired me to put the finishing touches on a piece that I’ve had on the go for a bit. There are two or three essays of the martyred Spanish-Salvadoran theologian Ignacio Ellacuría that are particularly attuned to this theme.[1] I’d like to offer a little overview of them at this time.

Historical action requires historical contemplation

Ellacuría’s starting point is always what he calls historical reality. He does not think that it makes much sense to speak of a Christian version of contemplation that has no historicity to it. This is a pretty common theme of the saints. Teresa of Avila would be horrified at a prayer life that attempted to bypass the sacred humanity of Jesus—a historical reality. John of Ruusbroec would find fault with any meditative project that attempted to silence the voice of the Scriptures and scriptural images—again, a notably historical reality. Ellacuría is in good company.

At the same time, the Central American theologian’s process of reasoning is different. He starts with the idea that we want to have active lives that make sense. A defence of action is quick off his pen; in fact, he says,

the moment of contemplation cannot be separated from the moment of action—as if the first ones were the truly spiritual moments and the second ones their mere results; as if the first were the place where God is encountered and the second the place where men and women are encountered. This is not to deny that one can distinguish methodologically between the moment of recollection and discernment and the moment of carrying something out, the moment of interior solitude and the moment of communication. But this does not entail privileging the moment of seclusion over the moment of commitment. Contemplation ought itself to be active, that is, oriented toward con-version and transformation; and action ought to be contemplative, that is, enlightened, discerning, reflective. The two great sources of this incarnate spirituality, each with its respective aids, are the word of God in scripture and tradition, and the word of God in the living reality of history and in the lives of men and women filled with the Spirit.[2]

Again, though, the idea that contemplation exists for the sake of good works is fairly traditional. To throw it out, you’d have to be more contemplative than a Carmelite and more Catholic than the Pope. Ellacuría remains in good company.

If, then, contemplation should not be sequestered and isolated from action, we need to consider what kind of prayer is conducive to the life we want to lead—the calling God has imbued in our situatedness and our very being. Ellacuría writes:

Contemplation in action can only mean the contemplation that can be done and should be done when one is acting. This does not only mean contemplating the action one has taken but transforming one’s past actions or future intended actions into what is contemplation strictly speaking, an encounter with what there is of God in things, and an encounter with God in the things. There is not, therefore, an open door to activism, or to abandonment of all forms of spiritual retreat, much less of liturgical celebration. On the contrary, it seeks to make explicit in word, in communication, in living, what one has found less explicitly in action. We know that it is found in action: first, because Jesus promised that it would be so in Christian commitment to those in greatest need; and, second, because the discernment of contemplation enables us to contrast that which is from God with that which is against God.[3]

Our action is not, of course, just whatever we want it to be. It has to be the kind of action that further’s God’s intentions:

The God whom Jesus proclaimed ought to be historicized among men and women, be made present and predominant in the world of men and women, so that God might be all in all, without annulling the specificity of particular structures and the identity of persons. It is not enough, then, that spirituality be missional, without this mission being oriented toward implanting the Reign of God.[4]

This means, according to Ellacuría, giving a critical eye to everything that we’re up to. Our action comes under scrutiny. Likewise, “contemplation can and must be scrutinized to see whether it is of God or something idolatrous.”[5] An idol in prayer would be some kind of diversion from who we are, a denial of where we are, a distraction from the life God has given us. It would further that movement of separation that Ellacuría has already rebelled against. It would make our prayer into something not just distinct from, but isolated from, our historical action.

The historical site of historical contemplation

When he discourses on the historicity of Christian contemplation, Ellacuría zeroes in on the notion of place. People have positionality. Prayer does too. If we don’t acknowledge this, we won’t get very far with historically situating our prayer—and perhaps, then, too, our action. It is imperative that we understand that

contemplation should be undertaken from the most appropriate place. The “where” from which one seeks to see decisively determines what one is able to see; the horizon and the light one chooses are also fundamental to what one sees and how one sees it. The where, the light, and the horizon in which one seeks God are of course precisely God but God mediated in that place chosen by God, which is the poor of the earth. This mediation of the poor does not limit, but rather strengthens the power of God as it is presented in scripture, in tradition, in the magisterium, in the signs of the times, in nature itself, in the march of history, and so on.[6]

Accordingly, where we undertake meditative and contemplative prayer is where God has placed us. This is specific and particular. But it’s also quite general. God has decided that the position from which we are to see the world is the place of charity. This involves two moments. One is the universality of charity, directed at the need that is before us, in the Parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10:25–37). The other is Christ’s self-identification with the poor in the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats (Mt 25:31–46). Ellacuría has a word to say about each.

First, let’s start with the fact that love demands a neighbour—someone with whom to break bread and share in action or act for the sake of. Ellacuría stakes a claim here, telling us that Christian contemplation should be related to action and focused on what the Gospel identifies as Christian action:

If this is the fundamental action in which we must be contemplative, then we must ask briefly what the Christian characteristics of this contemplation are. The fundamental point is given in action, because it would be an error of subjectivism to try to contemplate God where God does not want to be contemplated or where God cannot be found. The parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) is clear on this point: the true neighbor is not the priest or the Levite, who pass by the suffering of the marginalized and wounded, but the Samaritan, who takes responsibility for him and offers him material care, thus resolving the situation in which he is unjustly involved. This apparently profane, apparently natural act, one taken apparently without awareness of its meaning, is much more transcendent and Christian than all the prayers and sacrifices that the priests could make with their backs turned to the suffering and anguish around them.[7]

Second, Ellacuría speaks to the increasingly contemplative aspect. Contemplation has to go where action is; this Ellacuría takes from the Parable of the Good Samaritan. But contemplation also has to go where Jesus is; this is something that Ellacuría will take from the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats. We know that

Jesus—or that was the view of the early Christian community—identified himself with those who suffer. That is, of course, true of those who suffer for his name or for the Reign, but it is also true of those who suffer, unaware that their suffering is connected to the name of Jesus and the proclamation of his Reign. This identification is expressed most precisely in Matthew 25:31–46, and, indeed, that passage appears just before a new announcement of his passion (Matt. 26:1–2).[8]

Pope John Paul II said that the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats teaches us “those with whom he [Jesus] himself wished to be identified” (Novo Millennio Ineunte 49). Commenting on the same passage, Pope Leo has just last week told us that “contact with those who are lowly and powerless is a fundamental way of encountering the Lord of history” (Dilexi Te 5). Ellacuría thinks similarly. He also—I think quite correctly—associates Jesus’ declaration with the Paschal Mystery itself. The timing is significant. After Jesus is gone, where will we look for him? Ah, well, he has told us. And fortunately, he told us right at the end, right before the plot to eliminate him got under way; because we disciples tend to be a forgetful lot.

At this stage, we need to point out that yes, indeed, we are still talking about contemplation. In the Christian way of seeing things, contemplation can have many different proximate objects. It can have diverse loci. We can be alone with God in our intimate being, through the picture of Jesus in the Scriptures, as the creator of all the natural world that we experience—and in our neighbour, particularly the poor, marginalized, suffering, and excluded human persons whom the Lord chooses to identify himself with. These are all legitimate sites of Christian meditative, then contemplative, prayer. Ellacuría argues for this explicitly:

It is a confused prejudice to judge the degree of contemplation by whether the object of contemplation appears more or less sacred, more or less internal, more or less spiritual. That would mean assuming that God is more present, more readily heard or contemplated in the internal silence of idleness than in committed action. This may not be so, and there is no reason why it should be so.[9]

Ellacuría insists, quite rightly, that if we suppose that Christianity is a historical religion, with a historical revelation, in historical time, for historical people, then the kind of contemplation that is supremely historical in an ongoing sense—that is, inseparable from love of our neighbours (as in the Parable of the Good Samaritan) and seeing Jesus in those persons with whom Jesus announced his self-identification (as in the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats)—is not just an equally good kind of Christian contemplation. It’s the most historically needed kind of Christian contemplation.

Conditions of contemplation

Ellacuría is a realist. He doesn’t have his head in the clouds. For him, contemplation is not something that magically happens if we apply ourselves to action. We must acknowledge that “there is a great need for contemplation, and contemplation demands certain conditions without which there is little possibility of discovering what true action should be.”[10]

First of all, there is the simple need for a time dedicated to prayer, a space set aside for prayer:

Psychological and methodological conditions remain important as well; immersion in action is a rich source of reality, but contemplation requires special moments in which to gather up and consciously deepen the collision between the word of God heard in revelation and the urgent problems that reality raises in the mediation of its very self.[11]

But when we do this, Ellacuría insists, we can’t let our prayer become merely a time alone with God alone, as if Christianity were compatible with navel-gazing.

Although some conditions of contemplation pertain to time and place—opening the space within ourselves for God to be able to work—other conditions pertain to vigilance. God gave us his word. He revealed himself to us. We have to hold fast:

Some of these conditions are explicitly revelatory. It is not only erroneous but heretical to try to learn from praxis what God is saying because although God speaks and has spoken “in many and various ways” (Heb. 1:1), God has spoken definitively through the Son. and all revelation and tradition must be placed in this context.[12]

This brings us back full circle. We’re on the terrain of Jesus’ own words once again. So, if we were making an integral list of Ellacuría’s conditions for a Christian contemplative life, it would have to overlap with his ideas about historicity. Contemplation depends, then, on what we make of the poor. It depends, too, on what we make of the Beatitudes (Mt 5:3–12; Lk 6:20–23):

Contemplation depends on a spirituality of poverty; that is one way of interpreting what it means to be poor in spirit, knowing how to live with the spirit of poverty and identifying with the cause of the poor, understood as God’s cause. From this perspective of the poor, one sees new meanings and new inspiration in the classical heritage of the faith. Since this is a task rarely undertaken in the course of history, at least at the level of theological reflection, new things appear here that have been unnoticed by those who sat on the high mountaintops, the better to scan God’s horizon. The ones who see God most and best are those who have received God’s self-revelation.[13]

If we have failed to live up to this standard, however, Ellacuría is far from despair. We can always start. Indeed, we can always start again and anew. It is not just the Beatitude of spiritual poverty that matters (Mt 5:3). The Beatitudes also emphasize purity of heart (Mt 5:8):

Conditions of personal life should be remembered as well, because although God is made manifest even to the greatest sinner, that manifestation usually begins through conversion and purification; it is the pure in heart who see God best (Luke 5:8) [sic].[14]

This, I think, is where Ellacuría becomes even more approachable. If we have contemplated the Lord as creator of the cosmos, in our own intimate depths, and in the pages of the Bible, but not yet found him in the faces and flesh of our neighbours, particularly those who suffer, there is always hope. There are always new beginnings. The door is always open. If, when we have closed the door to pray to our Father (Mt 6:6), the lock has become jammed—no fear. He always, always stands at the door and knocks (Rev 3:20). There will always be a new opportunity to find him.

He is, after all, the Lord of history.

Feast Day of St. Luke, historian, evangelist proclaiming the good news for the poor

[1] Ignacio Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation” (1984), trans. Margaret D. Wilde, in Essays on History, Liberation, and Salvation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2013), 137–68; “The Crucified People: An Essay in Historical Soteriology” (1978), trans. Phillip Berryman and Robert R. Barr, in ibid., 195–224; and “Christian Spirituality” (1983), trans. J. Matthew Ashley, in ibid., 275–84.

[2] Ellacuría, “Christian Spirituality,” 281–82.

[3] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 163–64.

[4] Ellacuría, “Christian Spirituality,” 282.

[5] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 161.

[6] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 162.

[7] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 161.

[8] Ellacuría, “The Crucified People,” 223.

[9] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 163.

[10] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 163.

[11] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 163.

[12] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 163.

[13] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 162.

[14] Ellacuría, “The Historicity of Christian Salvation,” 163.