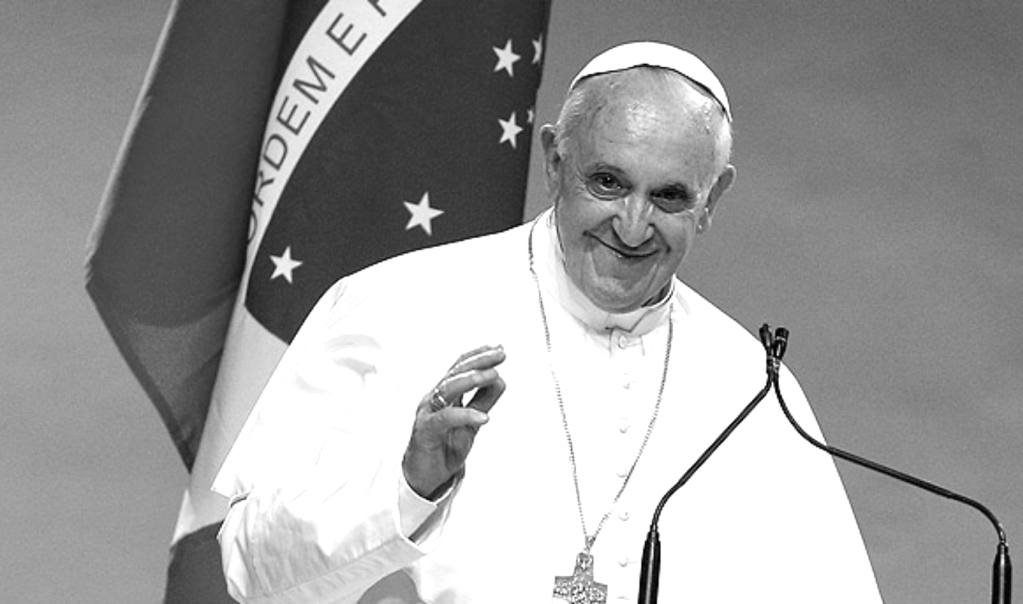

Early in his papacy, Francis of blessed memory gave a succinct summary of what he thought were four different currents of ideologizing that were floating around Latin America and the Caribbean. I’m thinking of his 2013 address to the Episcopal Conference of Latin America (CELAM) in Rio de Janeiro. What’s contained therein doesn’t seem to be a complete elucidation of all ideologies, but at the same time, the list of ideologies is broader than those normally focused on. What Pope Francis offers is complex and multidimensional. But it’s also simple. I come back to these words often:

There are other ways of making the [Gospel] message an ideology, and at present proposals of this sort are appearing in Latin America and the Caribbean. I mention only a few:

a) Sociological reductionism. This is the most readily available means of making the message an ideology. At certain times it has proved extremely influential. It involves an interpretative claim based on a hermeneutics drawn from the social sciences. It extends to the most varied fields, from market liberalism to Marxist categorization.

b) Psychologizing. Here we have to do with an elitist hermeneutics which ultimately reduces the “encounter with Jesus Christ” and its development to a process of growing self-awareness. It is ordinarily to be found in spirituality courses, spiritual retreats, etc. It ends up being an immanent, self-centred approach. It has nothing to do with transcendence and consequently, with missionary spirit.

c) The Gnostic solution. Closely linked to the previous temptation, it is ordinarily found in elite groups offering a higher spirituality, generally disembodied, which ends up in a preoccupation with certain pastoral “quaestiones disputatae”. It was the first deviation in the early community and it reappears throughout the Church’s history in ever new and revised versions. Generally its adherents are known as “enlightened Catholics” (since they are in fact rooted in the culture of the Enlightenment).

d) The Pelagian solution. This basically appears as a form of restorationism. In dealing with the Church’s problems, a purely disciplinary solution is sought, through the restoration of outdated manners and forms which, even on the cultural level, are no longer meaningful. In Latin America it is usually to be found in small groups, in some new religious congregations, in exaggerated tendencies toward doctrinal or disciplinary “safety”. Basically it is static, although it is capable of inversion, in a process of regression. It seeks to “recover” the lost past.[1]

Here, Pope Francis goes beyond listing modern Pelagianism and Gnosticism, as he did in some higher-order teaching documents (Evangelii Gaudium 94, 233; Gaudete et Exsultate 36–62; Desiderio Desideravi 17, 19, 20, 28). To these concerns about externalized action and noetic immanence, he adds concerns about individualizing and socializing tendencies—and for all four, he indicates common manifestations today. I really want to avoid all of these ideological distortions—but not least psychologizing, which is the most often forgotten instance of ideology, has played a prominent role in clerical mistreatment of myself personally, and is a key issue for a blog about contemplation to get a handle on. All four deviations matter.

Given this seemingly polar description of ideologies, Pope Francis’ implied solution seems to be dynamic movement among all four areas, developing and integrating each, not letting any get the upper hand forever, nor allowing our thinking to elucidate one aspect to the detriment of the others. Each dimension is part of our journey, even if each vocation is a different mix of them. For my own reference, I think of it a bit like this (because as a scientist and engineer, I like diagrams):

Of course, this isn’t just a diagram for people imbued with a spirit of technoscience. My little sketch of the late Holy Father’s response to ideology takes a lot of cues from medicine wheel models. What I draw here eschews linearized thinking, hyperfocus, and one-dimensionality—and that’s a way of thinking that, whenever it crops up in me, I owe entirely to my relationships with Indigenous people and what I have learned from them.

Still, whether we think of it as a wheel or not, it’s still a polar, multi-dimensional way of framing the dynamic of faith. And it points out the fact that, if we prefer one of these rabbit holes to the exclusion of others, especially its polar opposite, things are going to go badly wrong. Whether that comes sooner or later is the only question.

[1] Francis, Address to the Leadership of the Episcopal Conferences of Latin America, Rio de Janeiro (28 July 2013), 4.1.