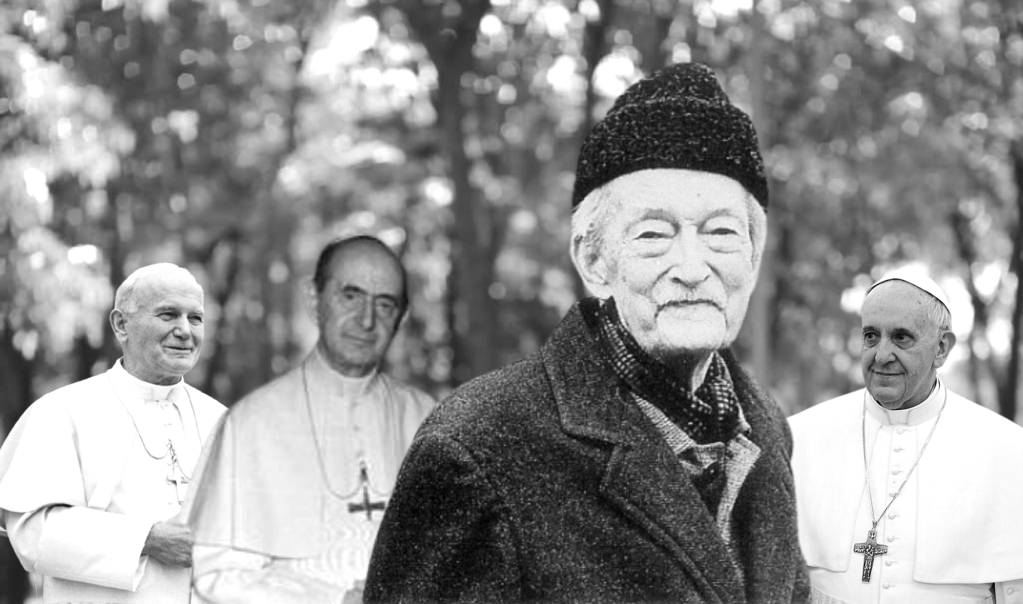

On this anniversary of the passing of Jacques Maritain, I want to take the opportunity to mull over the ways that he appears in papal teaching. As far as I can tell, four pontiffs have spoken to or about Maritain: Pius XII, Paul VI, John Paul II, and Francis. The case of Pope Pius XII, however, essentially amounts to diplomatic messages to Maritain when he was French ambassador to the Holy See.[1] Accordingly, it makes a lot more sense to start with Maritain’s friend and disciple, Paul VI. After that, I’ll move on to John Paul II and Francis—ending, where the late Bishop of Rome recently did, with the call to be “beggars for heaven,” an identification that is deeply personal to me and on which I will pause for a lot of digging.

Before starting, though, I want to say this: If the historical context of the earlier sections bores you, you can always skip ahead to the longer, hopefully fruitful discussion of des mendiants du Ciel or “beggars for heaven.” It makes total sense to me. That is where my own heart is.

Pope Paul VI

It is with St. Paul VI that Maritain starts to appear in papal gestures and teachings. Most conspicuously, the Frenchman was presented Vatican II’s closing message to the world of culture and science. Then again, sometimes he was a more hidden influence. He was, for example, the primary ghostwriter of the Credo of the People of God.[2]

Maritain’s cited appearances in Pope Paul’s corpus are diverse. On one occasion he serves as a global frame for discussion; an address to UNESCO both opens and closes with an invocation of Maritain.[3] Yet, at other times, the French philosopher responds to a point here or there. For example, an address to the United Nations as a whole cites some trenchant thoughts on democracy.[4] Other mentions, meanwhile, are more in-house. A slightly earlier general audience speaks of the meaning of contemporary atheism.[5] A letter to Étienne Gilson speaks of Maritain as “able to make Christians today, and many men of good will, so often troubled and confused, hear words of good sense, wisdom and fidelity.”[6] Paul VI also quotes a short book co-authored by Jacques and Raïssa to emphasize that contemplation is an integral and aspirational part of Christian liturgy:

“The liturgy itself demands that the soul tend toward contemplation and participation in the liturgical life… and toward an eminent preparation for union with God, through the contemplation of love” (J. [and R.] Maritain, Liturgy and Contemplation).[7]

Then, most importantly, there’s the encyclical Populorum Progressio. Although the explicit references are few, this document has Maritain written all over it. Pope Paul speaks at one place of a truly integral development and a new humanism, including love and friendship, prayer and contemplation; for that Maritain is the footnoted reference.[8] A little later, the pope again alludes to Maritain’s signature work of political philosophy, Integral Humanism.[9]

Finally, we come to Maritain’s passing—or rather, the day after. After discussing Catherine of Siena, whose feast day it was, Pope Paul mentions another voice:

And the other voice, which distracts and attracts us today, in an unpublished fragment of his, sounds like this: “Every professor tries to be as exact as possible, and as well informed as possible in his own particular discipline. But he is called to serve the truth in a more profound way. The fact is that he is asked to love first of all the Truth, as the absolute, to which he is entirely dedicated; if he is a Christian, it is God himself that he loves.”

Who speaks like this? It is Maritain, who died yesterday in Toulouse. Maritain, truly a great thinker of our days, a master in the art of thinking, living and praying. He dies alone and poor, associated with the “Little Brothers” of Father [Charles de] Foucauld. His voice, his figure will remain in the tradition of philosophical thought, and of Catholic meditation. Let us not forget his appearance, in this square, at the closing of the Council, to greet the men of culture in the name of Christ the Master.[10]

In sum, Maritain is for St. Paul VI a teacher, a philosopher, particularly in political and social spheres, and a theoretician-practitioner of contemplation—“a great thinker of our days, a master in the art of thinking, living and praying.”

Pope John Paul II

The Polish pontiff invokes Maritain to two ends and with two envisaged audiences. The first and smaller set of references is philosophical and theological. Maritain is set up from early on in the papacy as an example of philosophizing in line with the “signs of the times”:

I would like to recall that Paul VI wanted to invite to the Council the philosopher Jacques Maritain, one of the most illustrious modern interpreters of Thomistic thought, also wanting in this way to express his high regard for the Master of the 13th century and, at the same time, for a way of “doing philosophy” that responds to the “signs of the times”.[11]

Here, Maritain is all but set up as the post-conciliar model of philosophizing. Similarly but with less preeminence, in an address to Dominicans, Maritain is cited alongside Gilson as an illustrious contributor to their journal.[12] This is all capped off with Fides et Ratio. The encyclical letter on faith and reason lists Maritain when discussing the “fruitful relationship between philosophy and the word of God in the courageous research pursued by more recent thinkers.”[13] A particular example of this is presumably when he reflected on the “mystery” which is the Jewish people[14]—but certainly not only that.

The larger group of invocations of Maritain happens when John Paul II addresses French and European social and political personalities and organizations. According to the pope, Maritain ranks among those who have had “a crucial influence on social life in [France] and some of them also on the construction of Europe.”[15] He is an example of social engagement and one of the “great figures” of the past century.[16] He is noted as teaching on a personal and communal life that surpasses politics alone,[17] thanks to the “truly human life” of charity.[18] Indeed, that “truly human life” is the raison d’être of society.[19] Pope John Paul even cites the same page of Maritain on two consecutive days, when he declares that the human person “has an absolute dignity, because it is in direct relationship with the absolute.”[20] Ultimately, St. John Paul II’s main message about Maritain is that he said that society is “a task to be accomplished and an end to be attained.”[21] This is a real representation of the philosopher and statesman, if a little pared down.

Pope Francis

The Argentinian bridge-builder is a different duck from his predecessors. He mentions Maritain less frequently and in magisterial teaching of lesser orders. But—and this is vitally important—he adopts a quality-over-quantity approach. He enters much more deeply into the meaning of Maritain for the Church. Maritain is incorporated into some of the late Holy Father’s most intimate and probing reflections on truth, beauty, love, and finding a way of life.

Still, that pithy summary hardly does the reality justice. Francis doesn’t give his own distilled “essence” of Maritainism. No, not that—he explores the very “existential” ground of what it means, if I can so butcher language, “to maritain.”

Un thomisme vivant

The matter of truth crops up first, in an address to the International Thomistic Congress. Pope Francis took the opportunity to be abundantly clear about how he thinks scholarly study of and with St. Thomas Aquinas should function. This earliest reference in the Bergoglian papacy has a lot of similarity to the earliest reference in John Paul II’s corpus:

It is necessary to promote, following Jacques Maritain’s expression, a “living Thomism”, capable of renewal in order to respond to today’s questions. In this way, Thomism advances, in a vital dual “systolic and diastolic” movement. Systolic, because there is a need to focus on the study of the work of Saint Thomas in its historical and cultural context, to identify the structural principles and to grasp their originality. Then, however, there is the diastolic movement: to address today’s world in dialogue, so as to assimilate critically what is true and right in the culture of the time.[22]

To be alive you need both “systolic and diastolic” movement, says Francis. That is Maritain’s example. That is why we, the Popes, keep coming back to him. Francis reiterates what John Paul II had already promoted: there are many thinkers, but it could very well be that the fundamental example today is Maritain’s. Yet Francis forgoes framing the model in the Council’s terms (“signs of the times,” as John Paul II had said) and offers instead Maritain’s own: “living Thomism.” In sum, Francis makes John Paul’s contribution to our quest for truth grittier and more real—more rooted in Maritain’s own context and terms.

La littérature est impossible

Maritain also gets a mention as regards beauty and art—and the connection, or leap, to faith. Last year, in his letter on the place of literature in the formation of priests, Francis wrote:

As Jean Cocteau wrote to Jacques Maritain: “Literature is impossible. We must get out of it. No use trying to get out through literature; only love and faith enable us to go out of ourselves”. Yet can we ever really go out of ourselves if the sufferings and joys of others do not burn in our hearts? Here, I would say that, for us as Christians, nothing that is human is indifferent to us.[23]

First truth, then beauty—now onto love.

L’amour vaut plus que l’intelligence

Among the minor works that Francis finished up right before entering the hospital at the beginning of this year, there is a message to the President of France. The topic is a summit taking place on the topic of artificial intelligence. Francis quotes Maritain:

I ask all those attending the Paris Summit not to forget that only the human “heart” can reveal the meaning of our existence (cf. Pascal, Pensées, Lafuma 418; Sellier 680). I ask you to take as a given the principle expressed so elegantly by another great French philosopher, Jacques Maritain: “L’amour vaut plus que l’intelligence” [Love is greater than, worth more than, intelligence] (Réflexions sur l’intelligence, 1938).[24]

As I went over at length in a previous post, there seems to be a slight misidentification of the origin of this phrase; the reference is not, as far as I can tell, to Réflexions sur l’intelligence, but to an essay on the meaning of Christian contemplation, especially how it differs from that of the pagan Greek philosophers. What this means, then, is that, in Francis’ late invocations of Maritain, we move from truth, to beauty, to love—to a hidden pinnacle of the Christian contemplative life. The pontiff puts Maritain’s stamp on each of the transcendentals, then on the whole meaning of Christian love and living themselves.

Des mendiants du Ciel

Francis’ last Ash Wednesday homily spoke of “beggars for heaven.” With that, the Pope refers us again to Maritain. The purpose, however, is no longer to refine our thought about the transcendentals. Rather, the text offers a challenge to our lives. It also implicitly defines Francis’ own journey nearing its end:

Let us learn from prayer to discover our need for God or, as Jacques Maritain put it, that we are “beggars for heaven” (mendiants du Ciel), and so foster the hope that beyond our frailties there is a Father waiting for us with open arms at the end of our earthly pilgrimage.[25]

I could be wrong, but I think we have again a little sloppy referencing. I don’t think that the phrase mendiants du Ciel occurs in the writings of Maritain.

What I think Pope Francis has done is conflate a couple of things. The first is a quote from Maritain that speaks of us being beggars and speaks of the Father:

We can give nothing that we have not received, seeing as we are in the image of the One who received everything from his Father. That is why the more we give, the more we need to receive, the more we are beggars (mendiants).[26]

Second, there is the subtitle of the 1995 biography of Jacques and Raïssa by Jean-Luc Barré, which really is Mendiants du Ciel.[27] What both these conflated texts have in common is the godfather of Jacques and Raïssa, Léon Bloy. The authentic quote opens a Maritain book on Bloy. The biography subtitle, meanwhile, is a deliberate echo and fine-tuning of the title and subtitle of a book of Bloy, The Pilgrim of the Absolute, to follow up on the Ungrateful Beggar. With all these interrelated elements, we have pilgrimage, mendicants, and the Father. The pastiche that Papa Francisco is making, however, merits more exploration.

Those beggars for heaven

Throughout Barré’s biography of the Maritains, the phrase mendiant(s) du Ciel appears four times. Each instance is quite distinct. Assuming, as seems likely, that the late Holy Father read this book, we are left with a further assumption: Each of the four usages of the term “beggar(s) for heaven” throws light on what Francis means to point us towards and even to identify himself as. As I say, that’s an assumption. But I think we’ll find that it is not at all a stretch.

First, in the biography, Maritain is described as “more a beggar for heaven than a professor or philosopher.”[28] This is right for Jacques. It also fits Francis. He is the man who started a doctoral degree on philosophy and Romano Guardini, but put it aside. He is someone as astute as Maritain and as brilliant a thinker, but like Maritain, something other than a professor or philosopher. In Maritain’s terms:

The Ungrateful Beggar has an infinite need to give of himself. If he were rich, all the gold in the world would not suffice for his munificence; not being able to nourish with the riches of iniquity a whole people of the poor, he gives of himself, with an extreme abundance; he writes in order to give of himself. And his greatest bitterness is without a doubt that, among his contemporaries, too few want to receive what is offered to them with such love. There is, then, only one manner to act on men [and women]: to desire, out of the depths of desire, to serve them food. And it is in that, I believe, that the poor servant of Jesus most imitates his Master.[29]

Well, that fits. Those who bristled at Pope Francis typically wanted another professor-pontiff. It was frequently said in reply that they got a pastoral one. And that is very much true. But the pastor was one avatar among many. They—we—also and more fundamentally got the self-styled beggar for heaven.

Second, Barré says that Jacques and Raïssa gathered around themselves, as if by attraction, “beggars for heaven in their own image, men [and women] whom the irruption of faith had declassed or downgraded, thrown into side streets, and some princes in the shadows.”[30] This repeats many of Maritain’s own terms: “The Ungrateful Beggar had to give a voice to the impatience and agonies of a multitude of the poor and the forgotten that knocked at the door of his heart.”[31] He was compelled “to go beg in the squares and the streets,” whether physical or metaphorical.[32] We have already sampled these circles of beggars in the Cocteau–Maritain correspondence, cited by Pope Francis. Of course, that only goes to show something else. Francis is interested in Maritain’s approach. Indeed, it is quintessential Francis. We go to the streets and existential peripheries. The world is turned upside down. A ragtag circle is evangelized. Or perhaps its participants evangelize one another. Everyone is pulled into something so much greater.

Next, Maritain is described as “a beggar for heaven, an agitator of conscience.”[33] The maverick sanctity that attracts a messy circle doesn’t just exist and speak; it stirs consciences. It would be hard to deny that this, too, is Francis. If he knew how to do anything, it was nudge a conscience. One readily appreciates the appeal that this aspect of “a beggar for heaven” held for the late pontiff.

Finally, there is a plate of photographs in Barré’s book that is itself titled “The Beggar for Heaven.” It depicts an octogenarian Maritain, after he moved in with the Little Brothers of Jesus in Toulouse and ultimately donned their habit.[34] Apparently, the beggar for heaven is a disciple of St. Charles de Foucauld. He is someone who, though familiar with Br. Charles from the very beginning, as Jacques had been, ends his life immersed in that particular kind of contemplation. That is the case even though so many different projects have emerged along the way. But the fact is, none of them was satisfying. None of them constituted the whole of the mystery and the journey. None was definitional. I’m reminded in all this of Francis’ familiarity with Br. Charles from his time in seminary, of his closeness in his final years to the Charles de Foucauld spiritual family, of his unified but multi-stage life, and of his explanation of his intention to be buried at St. Mary Major: “The Vatican is the home of my last service, not my eternal home.”[35] It was a temporary work. His life was as a beggar for heaven. It won’t rest just in the earthly end, however ecclesial it may be.

As Francis, that Jacques Maritain of Popes, tells us, we “foster the hope that beyond our frailties there is a Father waiting for us with open arms at the end of our earthly pilgrimage.” In a pilgrimage, every project is partial. No step is the end. “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Mt 8:20).

What do we call this tremendous disposition to the upturning will of God that the Maritains practised and Francis, too, lived out? Is it an existential poverty? a personal vigil inside the dominical call itself? Is it simply the fire of hope? Whatever it is, those whose understanding of vocation borders on idolatry—those who interpret vocation primarily in terms of state of life, rather than state of life in reference to vocation—do not sound its depths. Insofar as this quivering virtue is part of any authentic life, it is demanding. But when it is seized in its Maritainian radicality, it is truly terrifying. It is a divine electricity that seems, at least subjectively, to be indistinguishable from constant instability, perpetual motion, immense frailty, radical dissatisfaction with anything except what is begged for, and the ecclesiastical fault lines and fractures that are almost certain to accompany all this.

Far from the solidity of Platonic forms, the beggar for heaven lives in a Heraclitean torrent. Each of us is tossed on the waves until God says, “It is enough.”[36] Yet, at the same time, God molds each of us like Adam, gently on his “maternal lap.”[37] Inside the whirlwind, the Father’s arms reach out for us—but they will completely envelop us only at the end. Both contraries coexist in one and the same reality. The beggar for heaven is not some celebrated traveller in search of sands which do not shift and constellations that never carry on. Never would he dare to live in that imagination. Something else impels him, something more shocking, more beautifully dangerous.[38] That prospect doesn’t paralyze him. But it makes him travel differently. As much as he ventures, he moves—to borrow an image of Alexis Ffrench—with broken wings on crimson skies. It would be an impossible feat but for the wind.

Francis saw beyond the philosopher, the professor, and the statesman. Few do. But he did. He found the Jacques and Raïssa whom I know and whom I took for genuine models. I know of no one else who has, in word and deed, identified so completely with this challenge of theirs, rather than making them into sturdy, but partly chipped, statues in the museum of philosophy, literature, and statesmanship. Their radicality is a whole calling. It asks not just one or two of the transcendentals of us, but all of them. Then it goes beyond their silent, still photographs. It thunders at the very root of being: beggars for heaven, or mendicants of nothing but the Kingdom.

I thank God for Pope Francis, because with him I feel seen—and never as seen, nor as close, as after his passing and after what can only be interpreted as a late declaration of identity. Let us learn that we are beggars for heaven.

[1] Pius XII, Address to the New Ambassador to the Holy See (10 May 1945); Address to Jacques Maritain and the French School in Rome (1 March 1948).

[2] St. Paul VI, Apostolic Letter “Motu Proprio” Solemni Hac Liturgia (Credo of the People of God) (30 June 1968). The promulgation of this text at the end of the Year of Faith was Maritain’s own idea, and the apostolic letter is almost identical to Maritain’s draft sent to Paul VI via their mutual friend Cardinal Charles Journet: cf. Michel Cagin, « Le Credo du Peuple de Dieu », Nova et Vetera 84.1 (2009): 7–43.

[3] St. Paul VI, Message to the Director-General of UNESCO (8 December 1970), 1, 23.

[4] St. Paul VI, Message to the Secretary-General of the United Nations Organization, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the United Nations (4 October 1970).

[5] St. Paul VI, General Audience (11 December 1968).

[6] St. Paul VI, Letter to Étienne Gilson (8 August 1975).

[7] St. Paul VI, General Audience (2 June 1970).

[8] St. Paul VI, Encyclical Letter Populorum Progressio (26 March 1967), 20.

[10] St. Paul VI, Regina Coeli (29 April 1973).

[11] St. John Paul II, Address at the Angelicum (17 November 1979), 5.

[12] St. John Paul II, Address to the Provincial Prior of the Order of Preachers in Toulouse (11 March 1993).

[13] St. John Paul II, Encyclical Letter Fides et Ratio (14 September 1998), 74.

[14] St. John Paul II, Address for the 25th Anniversary Celebration of the Declaration “Nostra Aetate” (6 December 1990), 2.

[15] St. John Paul II, Letter to the Bishops of France (11 February 2005), 5.

[16] St. John Paul II, Message to the President of “Semaines sociales de France” (17 November 1999), 8.

[17] St. John Paul II, Discours au groupe de spiritualité des Assemblées parlementaires de France (2 April 1997), 3.

[18] St. John Paul II, Meeting with the President of France (19 September 1996), 5.

[19] St. John Paul II, Address to Christian Democratic Members of the European People’s Party (6 March 1997), 5.

[20] St. John Paul II, Address to European Politicians and Legislators (23 October 1998), 2; Address to the Ambassador of France to the Holy See (24 October 1998), 3.

[21] St. John Paul II, Address to the President of France (20 January 1997), 2.

[22] Francis, Audience with Participants in the International Thomistic Congress (22 September 2022).

[23] Francis, Letter on the Role of Literature in Formation (17 July 2024), 37. The Cocteau–Maritain correspondence is an intriguing place to source one’s reflections on literature. I find it extremely plausible that part of the Bergoglian interest comes from a desire to accompany members of the LGBTQ+ community without bending Catholic doctrine, revisiting in our day the path Maritain already took with Cocteau in the 1920s. As will be seen, this ties into the mendiants du Ciel theme.

[24] Francis, Message to the President of France (7 February 2025).

[25] Francis, Homily for Ash Wednesday (5 March 2025).

[26] Jacques Maritain, Quelques pages sur Léon Bloy, in Œuvres complètes de Jacques et Raïssa Maritain, vol. 3 (Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires, 1984), 993.

[27] Jean-Luc Barré, Jacques et Raïssa Maritain. Les Mendiants du Ciel (Paris: Stock, 1995).

[28] Barré, Mendiants du Ciel, 97.

[29] Jacques Maritain, « Le Secret de Léon Bloy », in Œuvres complètes de Jacques et Raïssa Maritain, vol. 1 (Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires, 1986), 1029.

[30] Barré, Mendiants du Ciel, 150.

[31] Maritain, Quelques pages sur Léon Bloy, in Œuvres complètes 3.1001.

[32] Ibid., 3.996.

[33] Barré, Mendiants du Ciel, 542.

[34] Ibid., plates between pp. 317 and 318.

[35] Jorge Mario Bergoglio–Pope Francis with Carlo Musso, Hope: The Autobiography, trans. Richard Dixon (Toronto: Random House Canada, 2025), ch. 17, p. 195.

[36] Raïssa’s Journal, presented by Jacques Maritain (Albany, NY: Magi Books, 1975), entry for December 1933, pp. 229–230; Œuvres complètes de Jacques et Raïssa Maritain, vol. 15 (Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires, 1995), 363.

[37] Raïssa’s Journal, 14 April 1917, p. 42; Œuvres complètes, 15.191.

[38] This, ironically, being a shade of Jacques’ ideal Platonism—cf. Jacques Maritain, “The Philosopher in Society,” in On the Use of Philosophy: Three Essays (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961), 5: “Plato told us that beautiful things are difficult, and that we should not avoid beautiful dangers” (Œuvres complètes de Jacques et Raïssa Maritain, vol. 11 [Fribourg: Éditions Universitaires, 1991], 15).