This past week, the International Theological Commission released a new document. You probably haven’t heard much about it, because up until now, there is no English version. There are only German and Romance-language versions. I find this particularly odd and inexplicable, given that the topic of the document is the 1700th anniversary of the first ecumenical council. But there you go.

The Council of Nicaea is the origin of a lot of things in Christianity. A historian, particularly one following Pope Francis’ lead on the renewal of Church history today, would have a lot to say about it. I’m not a historian. But I do have a perpetual eye for language about Christian contemplation, especially when it rears its beautiful head on the Vatican website.

Working from the French version of Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour, I have found a strong contemplation-related patch near the middle of the ITC document. The framing of the reflections is that contemplation, contrary to what we might expect from the Greek heritage of the word, is not for the Christian a visual- or idea-based phenomenon. This claim, while quite broadly attested in the tradition, is a particular interest of Pope Francis. It appears as early as the first encyclical, Lumen Fidei. There is a recent allusion when the Holy Father draws on a text of Jacques Maritain that is a critical exploration of the relationship between ancient Greek and Christian contemplation.

The ITC takes up this important theme and speaks of contemplation as part of a relationship with a Trinity of Persons, each of whom is Mystery and Without Limit. The passage in question is as follows:

The knowledge of God through Christ does not offer a simple doctrinal content but it puts one in saving communion with God, because it plunges one, so to speak, into the very heart of reality, or rather, of the person to be known and loved. The prologue of the Gospel of John is an expression of the highest contemplation of the mystery of God who has been made manifest to us in Jesus so that we may enter, in the grace of the Holy Spirit poured out “without measure” (Jn 3:34), into the very life of the Triune God revealed by the Logos. (no. 74, emphasis added)

Subsequent to this (no. 75), the document cites the First Letter of John (1:1–4): we contemplate what has been seen, heard, and touched. That is, contemplation is not just cerebral. It’s not just ideas. It’s not just derived from or understood within a visual phenomenology. The Christian contemplates what—or rather, whom—the apostles heard and touched. The personal Trinity is in play. A living relationship is in play. But so too is the flesh of Jesus Christ, so too is the Incarnation. All this is of course very reminiscent of the Creed. It is very Nicaean.

The ITC, having established its theme, continues. It situates contemplation within the Christian’s participation in the life and states of Christ:

But Nicaea also indicates that this is the only way to access what the Creed expresses, both in its res [i.e., substance] and in its letter. We cannot contemplate the God of Jesus Christ, the redemption offered to us, the beauty of the Church and of the human vocation, and participate in them, without “having the mind of Christ.” Not simply by knowing Christ, but by entering into the very understanding of Christ, in the sense of a subjective genitive. One cannot fully adhere to the Creed or confess it with one’s whole being without “the wisdom that is not of this world,” “revealed by the Holy Spirit,” who alone “searches the depths of God” (cf. 1 Cor 2:6.10). (no. 76, emphasis added)

This passage is a succinct statement that contemplation is a gift, for we are to become of Christ and are given the gift who is the Holy Spirit—but note also, of course, the brief allusion to Pope Francis’s theme that what we contemplate is beauty.

After this mid-document reflection, the ITC is not completely done with contemplation. In fact, the ITC makes sure that the notion appears even in the concluding paragraph:

In today’s world, it is especially important to keep in mind that the glory we have contemplated is that of Christ, “meek and humble of heart” (Mt 11:29), who proclaimed: “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth” (Mt 5:5). The Crucified-Resurrected One is truly victorious, but it is a victory over death and sin, not over adversaries—there are no losers in the Paschal Mystery, except the eschatological loser, Satan the divider. (no. 124, emphasis added)

In other words, while it is important to stress the victory of Christ, this victory is no triumphalism. The Christ whom we contemplate is gentleness and vulnerability themselves. It is his Body into which we are taken. It is his Spirit whom he sends to us to enable us to contemplate him and to realize his defining character in the world. It is the self-same divine nature of the Father which Jesus makes manifest to us. God loves us vulnerably, as one says. There is no other Way (Jn 14:6), and everything that Jesus does he saw the Father do (Jn 5:19). Ultimately, the ITC summons us, even in a reflection on the first ecumenical council, back to contemplating the Jesus made known to us in the Gospels and in our living out of the life that he demonstrates therein.

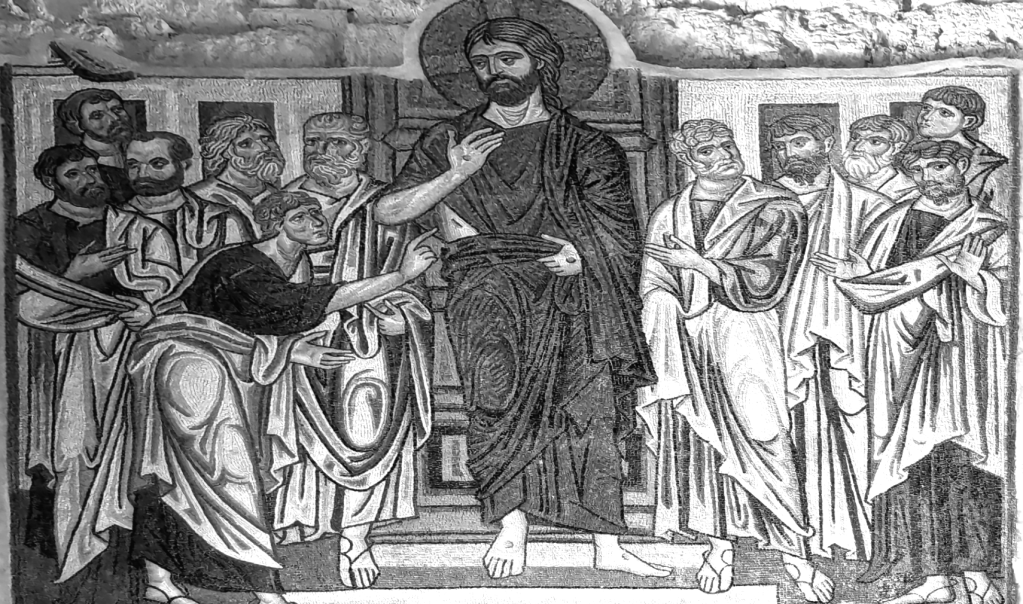

Featured image: Dafni Monastery, Athens suburbs, Greece