I have a particular devotion to Phoebe of Cenchreae, whose memorial is today (though overshadowed nearly everywhere by the feast of Gregory the Great). Unlike the case of many others who are close to her, however, my interest doesn’t arise because of her place in the ongoing ecclesial discussion about the (ordained) diaconate. It’s true, in the Bible, Phoebe is a diakonos (Rom 16:1–2). That’s part of her life story. But my own focus lies elsewhere. As with Prisca and Aquila and Lydia, I look to Phoebe as an early exemplar of early (lay) spirituality. When I recently took a pilgrimage through Greece, following in the footsteps of the apostle Paul, I didn’t neglect a stop at Cenchreae.

At the end of his letter to the Romans (16:1–2), Paul identifies Phoebe as a diakonos of the church of Cenchreae, to whom he is entrusting his letter, and he asks that the recipients of his message receive the messenger with respect, hospitality, and due love in Christ. After all, specifies Paul, Phoebe has been a benefactor or patron (Gk: prostatis) to Paul himself. This is an incredibly dense text which most people unfamiliar with ancient Greek, Classical Studies, and Biblical exegesis might simply rush through. But fortunately, aside from my interest in lay spirituality, I also have a graduate background in Classical Studies. I can pull a little more out of these two simple verses.

There is a lot behind the idea that Phoebe was a benefactor or patron of Paul. There were particular social codes about patronage in the Roman empire. Probably the most famous text that the average person might buy and read today is Seneca’s On Benefits. Suffice it to say, patronage wasn’t exactly our idea of friendship. If someone of higher social or economic status directed sustained patronage towards you, you effectively “owed” them. And then you were required, socially speaking, to speak well of these benefits and the person who bestowed them. The relationship would be ongoing and asymmetrical. Something like this is the normal meaning of being a benefactor or patron.

It’s obvious from reading Paul’s letters to the Corinthians that he did not like patronage one little bit. He deliberately makes a big deal of the fact that he worked with his own hands so as not to receive benefits from the businesspeople in Corinth (cf. 1 Cor 4:12; 2 Cor 11:7–15). He’s not going to be beholden to them. Why? Well, we don’t know. But quite frankly, the Corinthians were a pretty unruly and all-over-the-place bunch with a lot of problems. Corinth was a business city in Paul’s day, and Cenchreae was one of its two ports—the one facing towards Ephesus, not Rome. (For this reason and others, some scholars wonder if Romans 16 was originally from a separate document than the remainder of the letter, as Phoebe might be more likely to leave eastwards from Cenchreae rather than westwards; but for my purposes, this debate doesn’t matter.) The more middle-class and prosperous Corinthians were very much not like the stable, but poorer, churches from further north, especially Philippi and Thessalonica, which Paul could trust not to abuse the Roman idea of patronage and to take relationships more fluidly and equally in Christ.

Yet Paul identifies Phoebe, from just a few kilometres southeast of Corinth, as a patron of his. (How the Corinthians themselves would have boiled over with jealousy!) The easiest explanation is that he stayed at her place, as he did with Lydia in Phillipi (Acts 16:15), because she must have, like Lydia, been the householder and in charge of her own finances somehow. Such hospitality and financial contribution was the sense of her patronage. And presumably, Paul would have availed himself of the opportunity frequently enough. He could have walked from the centre of Corinth to the port of Cenchreae in one very leisurely afternoon. If there were a house church or two there, he would certainly have visited and supported it in its growth, however competent Phoebe and others may have been on their own.

From a spiritual point of view, then, this says quite a lot about Phoebe. Paul could very well have never stayed in Cenchreae. There is no reason, if he is to minister to the church in the port town, that he stay overnight there. He could have avoided getting embroiled in the complexities of the patronage system if he had so chosen. But he got involved anyway. Evidently, he trusted Phoebe. She wasn’t going to be problematic, confused, and limiting in her outlook like the Corinthians. There was no need to deny her the role of patron. She could adapt to the greater, socially-modifying demands of the Gospel and not take advantage of the position that patronage might put Paul in.

In short, from two little verses at the end of Romans, we get a picture of Phoebe as an envoy of Paul to other churches, who herself supported Paul in a mission area where he was very careful not to enter into relationships of support with the locals, who gave hospitality and was bold enough to also receive it on behalf of the apostle. She gives, but she takes. She knows the exchange of reciprocity in the Gospel, not bending social relationships into less equal and less mutually loving alternatives that her own culture had normalized for centuries. She was a layperson (?) who made use of her position and abilities for the sake of the evangelical message, its growth in her community, and its propagation abroad. Her role was support; it was hospitality. But she was vital and central for all that. Paul ranks her as his patron (prostatis) and servant-envoy (diakonos). Few people gain higher praise from the apostle than this woman from the port town outside this major metropolis of the day. Much of the way he phrases this praise is culture-specific and high-context. But it’s very real.

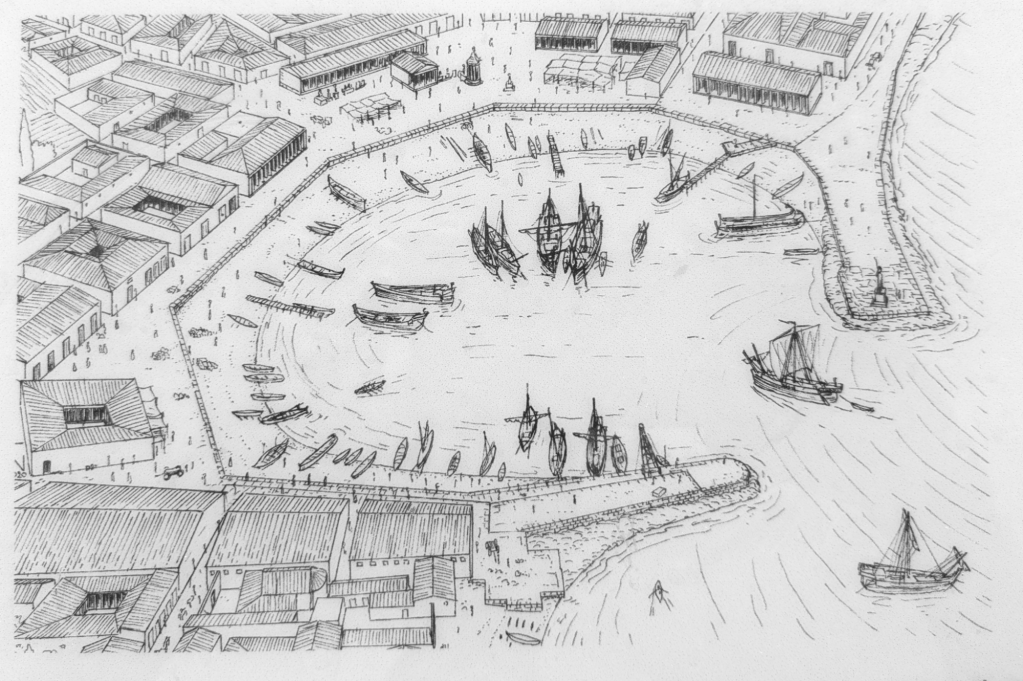

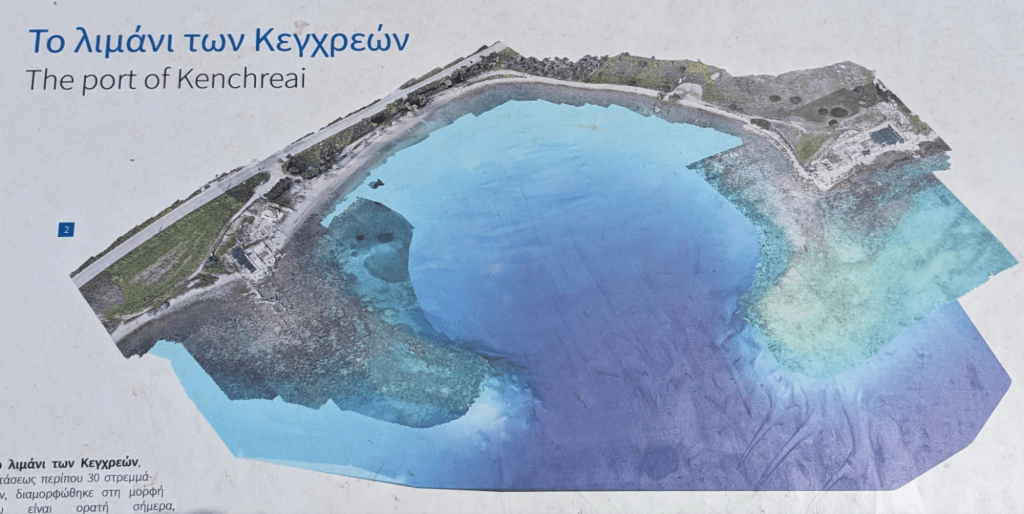

So I went to Cenchreae. It’s underwater now. The buildings along the ancient port sank. Some yellow buoys denote the extent of the moles. But you can further see the outlines of some structures from the shore (or if one goes snorkelling, which I came very much unprepared for). The surrounding beach is frequented by locals. Further archaeological remains from later eras line the shore. Entrance is free, since all beaches in Greece are by law public.

I stood there for a time taking in the geography, the layout, the ecology, the submerged foundations and walls. With a little sign of the cross and some unvocalized prayers, I addressed myself to Phoebe. She was why I had come. I am taken in by the lessons that her life teaches, in two short verses at the end of a letter and in a portion of text that scholars question was ever going to its ostensible destination in the first place—and a text debated endlessly in discussions about the ordained diaconate. For all these debates, perhaps in spite of them, maybe alongside them and an acknowledgment of their importance, we might take a moment to remember what we do know and what Phoebe does, without a shadow of a doubt, teach us about Christian spirituality: the centrality of trust, reciprocity, littleness, mutuality, and hospitality in the Church, still inspiring us twenty centuries later.