Although your local community probably isn’t celebrating it, today is the optional memorial of Prisca and Aquila, co-workers of the apostle Paul. For a variety of reasons, this lay couple are important to my own spirituality, and I’d like to offer some words on why, as well as give a little devotional material in visual form, from my recent pilgrimage around the Aegean.

Charles de Foucauld on Prisca and Aquila

We can trace a lot of my dedication to Prisca and Aquila to an unpublished letter of Charles de Foucauld to Monsignor Joseph Hours, dated May 3, 1912, from Assekrem (Ahaggar), Algeria (quoted in the little guide for Charles de Foucauld Lay Fraternities):

As you say, the ecclesiastical and lay worlds know each other so very little that one cannot communicate easily with the other. Certainly there has to be Priscillas and Aquilas on the side of a priest, to meet those whom he cannot meet, to enter into places where he cannot go, to reach out to those who have moved away from him, and to evangelize through friendly contact by becoming an overflowing goodness to all, a love always ready to give of itself, an appealing good example for all who have turned their backs on the priest, or maybe, through prejudice, are hostile to him.

He explains further a few sentences later:

Charity, which is the heart of religion, obliges every Christian to love his or her neighbour. (The first duty is to love God, the second like the first, is to love one’s neighbour as oneself). That is to say that one should make the salvation of one’s neighbour like one’s own, the important business of life. Every Christian, then, must become an apostle. This is not just advice, it is a commandment, the commandment of love.

In another quotation that I can’t track down again, Charles identifies the work of Priscilla and Aquila as “doing good in silence.” It is love in action that opens space between people for the proclamation of the Gospel.

We see these broad concerns manifested in, for example, Brother Charles’ 1914 directory for a Confraternity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, where part of its membership should be “fervent Christians destined to be lay missionaries like Priscilla and Aquila” who may exercise their commitment to evangelization and the local people “by settling there oneself if God so wills.”[1]

Although Brother Charles is not exactly the most reliable exegete and even stable holder of opinions, I think his general idea holds up rather well, though the lay couple does tend to do a fair bit more talking and educating than Charles lets on.

When Paul meets them in Corinth (Acts 18:1–17), they are workers recently arrived from Rome, with at least Aquila emigrated at some point from Pontus. Probably they are already Christians, of Jewish origin, and their labour is in the same field as Paul’s (leatherworking, commonly called by the restricted name tentmaking). Paul stays with them and works together with them.

Later, when Paul leaves Corinth, Prisca and Aquila leave with him (Acts 18:18). They depart from Cenchreae, so if Prisca and Aquila didn’t already know the diakonos Phoebe there (which is unlikely because Cenchreae is just one of Corinth’s two ports), they would have all met at this time (cf. Rom 16:1–2).

Paul briefly stops in Ephesus and leaves Prisca and Aquila behind there, while he himself goes on to Jerusalem (Acts 18:19–21). While Paul is away, it is not entirely clear what Prisca and Aquila do. Perhaps it is the job of Paul’s co-workers to get a new Christian community going. We’re not explicitly told. But we do know two things. First, Prisca and Aquila would need to work at their same trade in a new shop to support themselves. Second, we’re told they meet Apollos, an eloquent and learned Jew from Alexandria who explains the Way, but deficiently; the lay couple takes him aside privately and corrects him, and after some time, Apollos goes on to Corinth himself (Acts 18:24–26).

Paul’s letters also testify to the importance of Prisca and Aquila. Assuming that the entirety of Romans is indeed directed to that community, at some point Prisca and Aquila made it back to Rome, to be greeted as Paul’s “co-workers in Christ Jesus” (Rom 16:3). In the long list of names in Romans 16, Paul addresses these two first, just as he (and usually Luke) always puts Prisca’s name first. The couple is again greeted in a pastoral letter (2 Tim 4:19); this may testify to the need of a later generation of Pauline writers to show respect to Prisca and Aquila’s mission, or if the letter is indeed written by Paul, it shows the couple’s continued dedication to the Way and its spread.

In short, Prisca and Aquila are lay co-workers of Paul—both in trade and in Christ Jesus. While it is entirely possible that Brother Charles’ characterization of Prisca and Aquila is correct, it could also be true that they engaged in a bit more active teaching and community-building, not just in response to Apollos’ errors, but also as a matter of course. Regardless, Paul is evidently depicted as the main preacher of the Gospel in Acts, and Prisca and Aquila do have a different manner of behaving. They do represent a style of evangelization that is immersion in a particular world—in their case, that of the working-class artisans of the ancient Mediterranean, Greek and Roman.

Traces in Corinth and Ephesus

One of the big questions about Prisca and Aquila is how and where they worked. It’s what interests me from the point of view of classical studies, and it’s what interests me from the point of view of lay spirituality.

Last month, I went to (among other places) Corinth and Ephesus, so I did a little exploring and praying for myself.

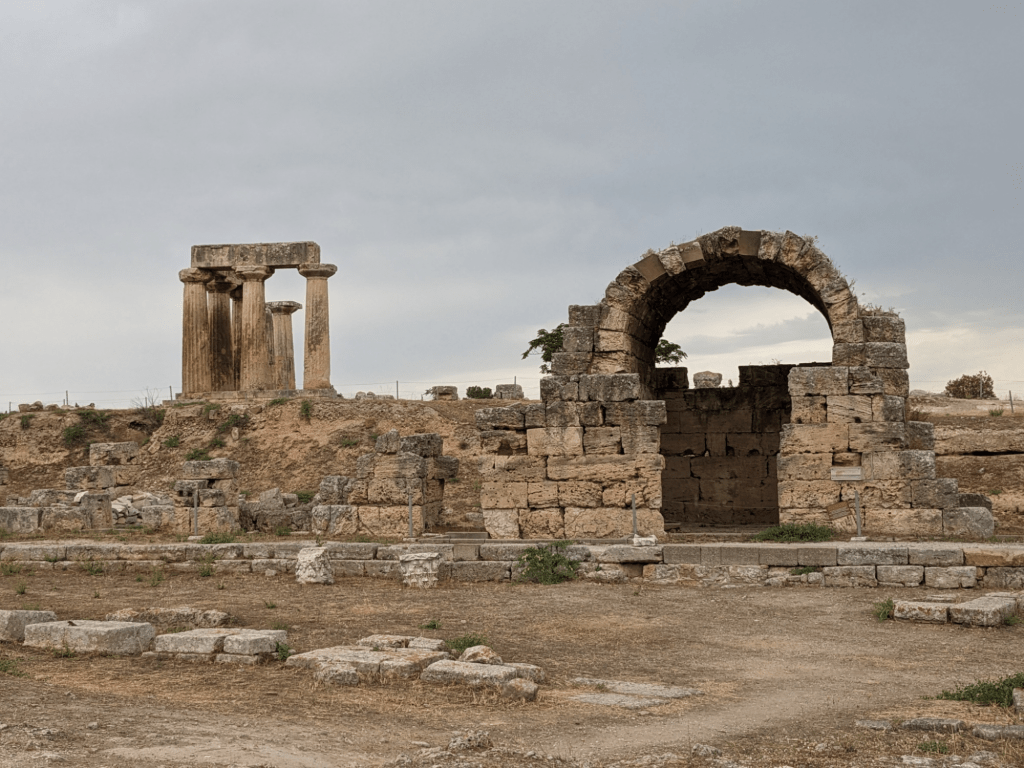

In Corinth, there are several rows of shops that are still in fairly good shape around the main agora/forum (where Paul goes on trial before Gallio). Their arrangement is such that they are in the shadows of different temples (to Octavia, to Apollo and maybe Caesar). Other agoras existed, too, off other streets not far away. But whether or not the location of Prisca, Aquila, and Paul’s shop was there on the main square, surrounded by symbols of imperial power in every direction and within eyesight of the podium from which the brief trial before Gallio took place, the general design of the shop room would be the same.

Each shop is a narrow room with a barrel-vaulted roof. It’s pretty tall, and there were likely or usually boards added for a mezzanine, on which people might sleep. Maybe Paul would have had to sleep on the lower level, among the shop things, while the couple retired to the mezzanine. (Alternatively, Prisca and Aquila might have rented an apartment or owned a home—but the latter is improbable given ancient economics and their itinerant lives.) If you want to learn about the leatherworking trade and the implements that would be there in the shop, I’d recommend any number of books by Jerome Murphy-O’Connor on Paul.

I wonder how many early meetings of Christians took place in these rooms. Leatherworking is a relatively quiet occupation, so maybe the trio laboured and taught passersby at the same time. Or maybe when the day’s business was over, Christians were meeting in places like this for their “house church.” At any rate, Prisca and Aquila were evangelizing by presence and charity as they laboured there. There is a lot to ponder.

But may it spur us on to, at the minimum, a commitment to the ministry of presence: “Priscillas and Aquilas […] enter[ing] into places where [the priest] cannot go… reach[ing] out to those who have moved away from him, […] evangeliz[ing] through friendly contact by becoming an overflowing goodness to all, a love always ready to give of itself, an appealing good example.”

[1] Charles de Foucauld, Règlements et directoire (Paris: Nouvelle Cité, 1995), 701–704.