One of the best guides I have ever had in my own spiritual life is the writing and personality of Jacques Maritain. He was a rather more rigorous intellectual than I am—but I have a decent blend of him, Raïssa, and her sister Véra in me, all three, so I have always expected that he would understand my situation.

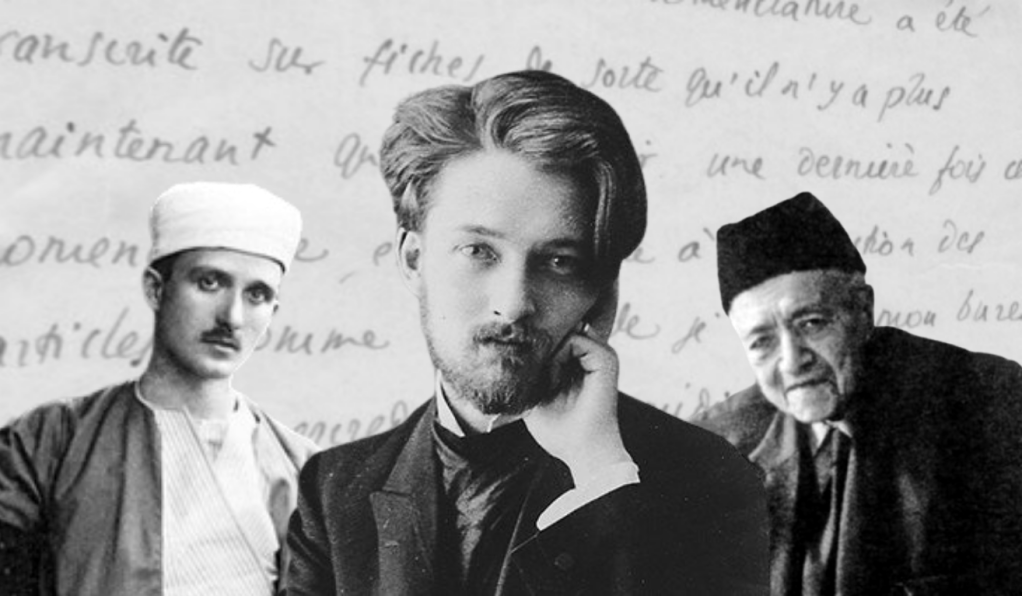

One thing that the Maritain trio was always committed to was a contemplative project realized in the world. This shows in their support for the nascent Little Brothers of Jesus and the spiritual family of Charles de Foucauld. But it starts much earlier. In fact, they helped point those who entered the spiritual family and started branches of it to find their own way. Two of the correspondents and friends that received immense orientation and assistance were the prominent scholars of Islam Louis Massignon and Louis Gardet.

Both Massignon and Gardet needed some spiritual direction of a sort—or at least some advice. They were tempestuous souls, given to extremes or unable to discern a path, for what they were attracted to for a mode of life did not yet exist. Jacques in particular took on an active role in guiding them, moderating impulses, and sifting through thoughts to forge words that they could hold onto in the blustery storm.

Two of the earliest letters that he wrote to each of the two Louises are remarkable for their clarity of vision, first of the Christian life in its essence, free especially from Pelagianism and Jansenism, and second of the contemplative life, not in its essence but as regards its meaning if lived in the midst of the world (outside the cloister). Here are the densest cores of those letters, in full and without intrusive commentary.

Jacques Maritain to Louis Massignon, January 20, 1914: God wants us above all to be one and simple[1]

You are not relaxed enough, happy enough. “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I say, rejoice” [Phil 4:4], says Saint Paul. It seems to me that you are searching too much, that you are too preoccupied with a host of questions, that you want too much to establish order in your soul and in your life yourself and through conscious effort. We never do anything good on our own. “Throw all your concern into our Lord, and he will refresh you” [Ps 55:22]. God lives in us; he is there, he acts in us, he will know how to bring order in us if only we make silence in ourselves to be attentive to his presence: that, and nothing more.

It seems to me that you are confusing merit with effort. It is charity and not pain that alone creates merit. It’s not about systematically doing what we don’t like, any more than it’s about doing what we like. It is about losing sight of ourselves, to look at God alone. There is nothing good in winning; there is only losing, looking at ourselves and analyzing ourselves. The Blessed Virgin deserved more than all Christians, and she had joy in following the divine will.

Grace truly makes us children of the good God. This is not just a beautiful word or a metaphor; it’s reality itself. So let us act accordingly. We belong to this lineage, spring from this heredity if I dare say so; it engenders the dispositions and tendencies to which we must be drawn. As much as it is true that ”we will die if we do not do penance,” it is also true that there are certain joys of the soul that we must seek, “always seeking the better,” within limits, of course, for the order desired by God. Our Lord came to bring festivities on earth. You don’t always have to work. To satisfy certain attractions is to follow the very direction towards God planted within us. If we have the means, and if nothing stands in the way of strict duty, we must, for example, sacrifice many things for the joy of a more or less prolonged monastic retreat. Refusing the joys that God offers and gives is the great sin of the Pharisees and Protestants. Remember the parables: our Lord invites us to weddings and feasts. Will we always answer: I bought a pair of oxen, or do I have a state of life or job that is holding me back? …

I know very well that all this is for God alone. But this is precisely why I must warn you (as you are right to warn me not to put off righteous minds who seek in the sciences). God wants us above all to be one and simple, above to come to him as little children. The usefulness of what we can do is nothing, absolutely nothing, compared to this. And besides, God alone is master of the usefulness of our efforts. I believe that here you have given yourself a burden which exceeds human strength, and which goes against the simplicity of providential ways.

Jacques Maritain to André [Louis Gardet], July 1928: To be a contemplative in the world is to be usefully devourable[2]

A life integrally contemplative in the world? To be honest, I don’t think it’s possible. A contemplative life in its essence, yes, and even one that does not care for the mixed active–contemplative life of (for example) the Dominicans, yes, that is possible, too. But this kind of contemplative life lived in the world could find no other justification than to attend to the deep desires of souls, to be in some way or another given to them, to support them courageously through all the troubles, bitterness, and useless ups-and-downs that are inseparable from the traffic of humanity. In other words, this contemplative life must give witness in their midst to contemplation itself and to the Eucharistic love of our Lord…

If you must stay in the world, I believe that it is with the will to let yourself be devoured by others, only keeping the part (a pretty big part at that) of solitude that is necessary so that God makes of you something usefully devourable…

[1] Jacques Maritain & Louis Massignon – Correspondance (Paris: DDB, 2020), 49–54.

[2] Maurice Borrmans, Louis Gardet (1904-1986). Philosophe chrétien des cultures et témoin du dialogue islamo-chrétien (Paris: Cerf, 2010), 19.