When the Holy Spirit comes down upon us and animates our actions from within, this affects the dispositions of our body. Over time, these actions, in their unpredictable variety, begin to shape the features of our face and the comportment of our joints and muscles. Marie-Joseph Le Guillou, following quite a bit of the tradition, calls this transfiguration in Christ.[1] Charity affects the whole person. Le Guillou’s trademark phrase seems to be this one: “Charity has to pass all the way to our fingertips. If that doesn’t happen, something is awry!”[2]

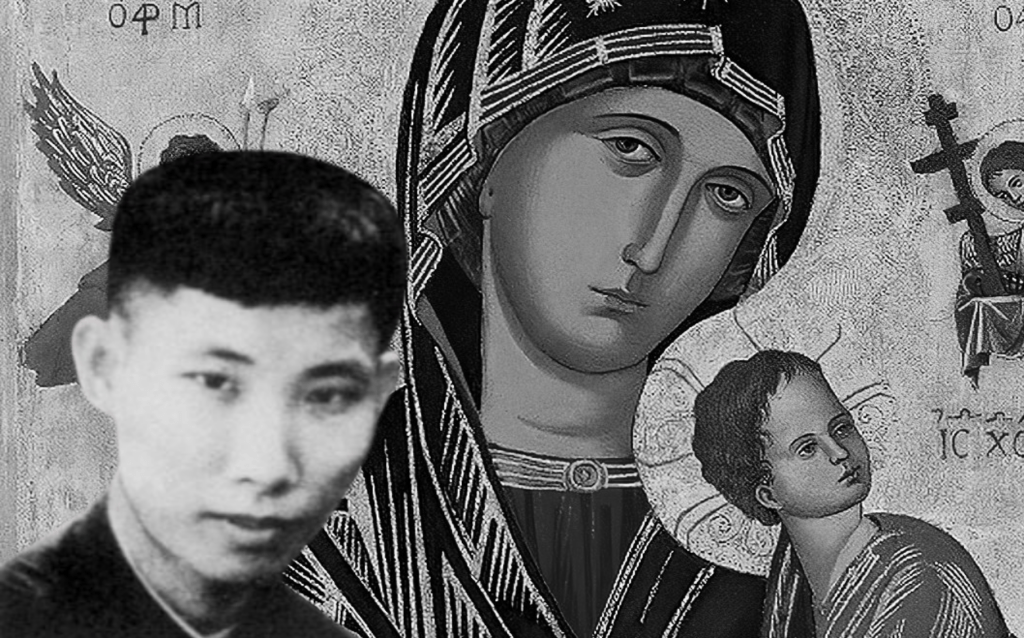

Marcel Văn is quite preoccupied with this theme, even though he doesn’t know it by name. For Văn, love is beautiful. And it is visible. He wants it to be seen, not just in actions, but in our flesh. Although the theme is broader in his writings, the two transfigured features that, in my judgment, seem to stand out the most belong to the face: the mouth and the eyes.

In fact, when it comes to the mouth, I will talk just about the feature of the smile. This won’t capture the whole story. In Vietnamese, “to smile” and “to laugh” use the same verb (cười), while the noun forms “smile” (nụ cười) and “laughter” (e.g., tiếng cười, “language/word of smile/laugh”) are different. It is not quite right to neglect laughter in this story. And Văn talks about it a lot. To express ourselves here in simple terms, we could say that the smile is to transfiguration of the visual just what laughter is to transfiguration of the auditory. In the prologue to John’s Gospel, we see his glory, but he is the Word (cf. Jn 1:14). In the Synoptics, the cloud on Tabor is bright, but Moses, Elijah, the Father, and Jesus all speak (cf. Mk 9:2–7; Mt 17:2–7; Lk 9:28–35). They do go together. Transfiguration is not limited to one of the senses.

I intend, nevertheless, to put laughter to one side, if for no other reasons than to keep a better balance between eyes and mouth, to keep this post from getting far too long, and to not digress into a discussion of “changing sadness into joy,” because evidently the things Marcel says about laughter would bleed into that theme very, very quickly. Indeed, it would even be possible to divert discussion of the transfigured smile in that direction: “I love Jesus very much and it is because I love him that I see all the sufferings of this world change themselves into so many smiles” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 2 Dec 1950).[3] I will try to avoid this. I want to zero in on transfiguration of the body as a theme.

Background

Văn knows about transfiguration of the body, if not from the teachers and preachers in his life, and perhaps not explicitly by name, but at least from his big sister Thérèse and implicitly. In Story of a Soul, it is recounted of a toddler Little Flower looking at the heavens: “there is something so celestial in her gaze that one is ravished by it” (Ms A, 11r).[4] People remarked about Thérèse’s heavenly eyes and seraphic look as a child (STL 44, 65, 103, 154).[5] Of her father, the author of Story of a Soul says that “his beautiful countenance [figure] told me so many things” more than a preacher’s voice for “so much did his soul love to immerse itself in eternal truths” (Ms A, 17v). When Thérèse receives a vision of the Blessed Virgin that heals her, she struggles to make others understand that it is “only her countenance” (sa figure seule) that struck her, and the incomprehension of this perspective humiliates her (Ms A, 31r).

Love and joy on the face

Marcel is deeply concerned with both the snapshot and long-term implications for emotions to be manifested in the body. Perhaps this comes partly from his experience with psychological and spiritual abuse. Perhaps it is simply his natural precociousness and hypersensitivity. In either case, the perception and focus are real: “‘When one loves, a deformed face becomes a flower, when one hates, a pretty face becomes deformed.’ This proverb is true always…” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 22 Sep 1951) It is important in our moral life not to forget this.

There is a tension here between that which is conscious and under our control and that which isn’t. We can put up a good fight and, with the Spirit, put in some concerted work on our facial expressions and bodily gestures. But we can also be unaware of the torrents that rush underground in us, disfiguring our faces with negative emotions projected onto others. At the same time, the work of the Spirit can also be positive and pass above our conscious apprehension (e.g., Exod 34:29). Marcel testifies beautifully to this latter:

From the day when my two friends Tám and Hiển noticed the reflection of an extraordinary joy on my face (at least that’s what I heard them say in low voice when they were chatting to each other, since for myself I was unaware that there was anything unusual about my face), I felt clearly at the bottom of my heart a spring of inexhaustible happiness. (A 630)[6]

Văn continued to think he had a “customarily friendly face” throughout his postulancy (A 811). Later, though, during his novitiate, Marcel was conscious of losing his natural smile and aware that some people said he had a nasty look about his face (Conv. 7, 683–684, 697; cf. the latter letter To Lãng, 22 Apr 1951).[7] At this time, Jesus emphasized to him that external beauty does not attract him, but rather beauty of soul (Conv. 2–3, 7, 684), that he does not even want Marcel’s beauty and joy to appear externally (Conv. 18, 41, 48, 70), that nothing is more beautiful than to do the will of the One one loves (Conv. 14, 36, 93; see also the later testimonies To Tế, 7 May 1952; To his parents, 1 Feb 1953; OWN2.82; OWN6.13)[8] and always pleasing Jesus (Conv. 443), and that the greatest beauty of Jesus himself was his Love for us (Conv. 515). Still, it seems pretty clear that Văn understood that, even though interior beauty trumps external charm, transfiguration of the body is real.

I think there is an argument to be made that, when it comes to transfiguration in Christ, the things we see in others tend to be the same ones that God is working in us. I’ve noted the phenomenon previously. I’m going to operate on the assumption that the hypothesis is true. I’ll divide the subsections accordingly.

What others see in him

Although it is true that Văn and the people in his life, at least as recounted in his autobiography, noticed things like lips (A 24, 135) and eyes (A 188, 236), he acknowledges that this is “natural beauty” (To Tế, 3 May 1950). I am here interested in supernatural beauty in more general terms, and what I am focusing on here is transfiguration—taking up what is natural into a supernaturalized, charity-informed configuration of matter.

Văn is aware that others see this in him. While still a young child, a Buddhist neighbour of his aunt says, “Your lips are very pretty. It is certainly heaven which rewards you for never having used bad language.” (A 105) That’s interesting. This person isn’t even a Christian. We can take this background as grounding for what Marcel will see in others—Jesus, saints, neighbours.

What he sees in Jesus

As I wrote in another post, Marcel tended to see contemplative prayer in terms of beauty, and he wrote a lot on this in connection with the profession of religious vows. In fact, on one of the occasions that Marcel describes his upcoming profession as an opportunity to contemplate the beauty of Jesus and for Jesus thereafter to contemplate his (Marcel’s) beauty, he singles out contemplating a “mutual smile” (Conv. 704). In one of Marcel’s visions, too, Jesus is described, and two of the few features mentioned are a smiling face and lips that are fresh and bright red (Conv. 182). What others see in him at his transfigured best, he wants to see in Jesus.

This is a constant theme. It doesn’t seem to ever disappear. One poem and its commentary constitute a good illustration. Marcel quotes his poem and then discusses its meaning, and I quote this at length because of how much it informs our thinking about transfiguration in Marcel’s life. Speaking of Jesus, who is his constant companion, he says:

This lover with the charming lips

And the passionate gaze,

…

Following the experience of the loving heart, I affirm that the lips and the eyes are, in my opinion, the two organs which express best the feelings of love, since it suffices for a simple glance and a gentle movement of the lips which trace out a smile to immediately understand the feelings of the lover’s heart. These two organs can show the love which overflows from inside.

In my opinion, this explanation consists of nothing which is bad, it is the simple truth; and if there are some people who see in it something unbecoming, they do not yet understand that their experience of the love of God leaves something to be desired.

Before writing these two phrases, I hesitated, and I intended to leave them to one side, but seeing clearly that they were in accord with the truth and described things that I had often observed relating to Jesus, this experience compelled me to write them. If one has nothing to describe, how can one speak of “Love”?

Whatever it may be, the description comprises nothing external and the words “charming lips” indicate quite simply the gentleness and the tenderness of the heart of Jesus; and if he moves his lips to speak it is to tell us of his love. As for the expression “passionate gaze” it again signifies love, generous and limitless, which overflows from his heart…. Oh! how beautiful he is! How worthy he is of being loved! (OWN8.22–24)

This is a really involved passage. It raises a lot of important points. I think it provides a key to Văn’s lifelong fascination with smile and gaze: “the lips and the eyes are, in my opinion, the two organs which express best the feelings of love.” Why? Simply because “it suffices for a simple glance and a gentle movement of the lips which trace out a smile to immediately understand the feelings of the lover’s heart. These two organs can show the love which overflows from inside.” They are, in Marcel’s judgment and experience, the most susceptible to transfiguration.

Marcel knows that saying so will incite disbelief and even criticism from some quarters. But he believes it anyway. He “hesitated” to write these lines of his poem—but he went for it regardless. He doesn’t mean anything “external.” These are wonderful, beautiful descriptions of the beauty of Jesus that shines out from the interior.

Another poem continues the dual theme of transfigured, grace-filled mouth and eyes. Marcel highlights the mouth and eyes of the child Jesus, sitting there in Nazareth:

O Jesus… There you are smiling at me!

How charming are your lips

And your gaze so captivating.

… Why do you smile at me so? (OWN10.1)

And another with the smile:

Oh! Oh! Look, he smiles at us

With his pink lips pretty like a flower’s bud. (OWP8.2)

And again with the loving regard:

The gaze of little Jesus

Brothers, have you seen it?

See, he is looking at us;

He seems to really want us in looking at us so,

In looking at us for such a time.

Brothers, see how dazzling is his gaze:

He looks at us from afar but with such ardour.

Ah! Ah! Jesus looks at us

It seems he wants to ask a kiss from us. (OWP8.4)

The Holy Innocents, Marcel’s imaginative playmates, are similarly exhorted to contemplate the beauty of Jesus:

Yes, brothers, let us contemplate our Jesus

Like a flower in Mary’s hands.

Look! Look! There is Jesus

With the smiling lips and pink cheeks of ravishing beauty. (OWP8.1)

We can keep looking at the same theme in poetry, with “an amusing piece” called “The Secret Kiss” (OWP14):

On a certain twenty-fifth of the month (25 January 1951), two angels walking together make a stop at the novitiate.

They see there a small child in a deep sleep and of a beauty so extraordinary that they are enchanted and cannot contain their curiosity. The younger of the two angels posed this question immediately:Who, therefore, is this child sleeping so peacefully

And who seems to be smiling at the flowers?

How charming he is with his shining face

And lips of a ravishing beauty!

Note the regard for flowers. Often Văn compares beautiful things to flowers or suggests that gathering flowers is an activity full of joy, particularly when those flowers represent souls, and Jesus or some other person is gathering them. The poem also notes a more general “face of love,” to be kissed on the cheek secretly so as to note awaken the sleeping child Jesus.

As a final example from Marcel’s poetry, consider a dream close to the tabernacle (OWP16):

After a while, he did not cease fixing me

With his gaze so full of love…

Then, holding me tightly, he gave me a kiss…

I lost consciousness! And my soul remained enraptured!Then my dream vanished;

The noise of the wind brought me down to earth.

Throughout the poetry, we come back again and again to the same facial features: eyes and mouth. The way they are discussed as beautiful, transfigured, and divine in regards to Jesus is by referencing the lips (which would smile for and at us) and a gaze (which fixes itself on the other, without self-interest, to accept the other’s constitution, nature, and dignity). This is appreciation of beauty.

What he sees in others

Christ is continued in others, “members of the mystical body of Jesus and also our brothers” (A 176). It should come as no surprise, then, that Văn finds the same transfigured beauty in other people, or at least tries to.

The starting point for reflection here should perhaps be Mary. Like her Son, she is characterized by a smile (Conv. 243-1). And a poem tells of the devotion to and effects of the gaze of the Mother of Perpetual Help:

Above all at times when I am exhausted

You never neglect to look at me.

In unrest as in danger,

Your gaze is my comfort and support.Oh! Mary I love you greatly!

A glance at your face is enough to reassure me;

A glance at your face is enough to melt my sadness;

A glance at your face is enough to regain my peace. (OWN1.3)

Another saint dear to Marcel gets the same treatment. Maria Goretti, whom he venerates, perhaps partly in relation to the sexual violence he himself endured, is spoken of in poetry in terms of her smile:

Maria Goretti!

Young girl!

You know how to show a smiling face,

To keep your soul in uprightness and peace.

You are our model! (OWP12.4)

Note in particular the use of the word “model.” How is Maria Goretti Marcel’s model? To be sure, this question admits of a multifaceted response. Yet the immediate context here does include “a smiling face” in the description of the saint. Something about transfiguration of our flesh should inspire a desire for the same to become active in our life.

Marcel, however, does not stop at the Mother of Perpetual Help and the communion of canonized saints. Descriptions of his confreres can mention smiling (Conv. 278). I think, though, that he is more reticent and circumspect here, for obvious reasons. Individual attachments that become too involved in religious life are not conducive to growth in community life, and Văn seems to have a sense that he needs to be careful to avoid this kind of thing. He observes others forming such attachments with him and dislikes the fallout (To Brother Andrew, 22 Mar 1850; OWV 784–782). Accordingly, he doesn’t like to dwell on individual positive interactions, except when they have given him some help for which he is going to pause for some time in gratitude to Jesus. The choice might not be exactly the same one we’d make today or in our own circumstances, but he has his reasons. Anyway, he does observe and appreciate.

What he offers to Jesus

Finally, after people finding transfiguration in him, dwelling himself on the beauty of Jesus, and finding transfiguration in others, Marcel will consciously offer his own metamorphosis back to the Lord. This is the crucified dimension of transfiguration. Here emerges a shard of pain—maybe twenty, thirty slivers of agony. Even when he is sad, dry, or on the verge of despondency, Marcel will offer his body to his Beloved:

This poor heart in its dryness

Can but offer you a smile of love. (OWP19)

And again:

Jesus, my brother, I see your smile

Which reveals to me all the love of your heart.

Accept willingly that my love

May be for you, warmer and stronger. (OWN10.3)

Văn’s life has known much turmoil and suffering. He thinks that he can best explain his situation to a priest he knew previously by saying, “I have never lost my smile” (To Father Dreyer Dufer, 8 Aug 1946). He keeps it. It’s deliberate. He needs the Spirit to make it not disappear, but the conscious effort is present, too.

Beauty need not imply physical perfection. There is an argument to be made, too, that Văn’s concern for the beauty of smiles is betrayed when Jesus comforts him that his “mouth is now a little bit prettier” after having a tooth extracted (Conv. 446). As long as the divine beauty shines through, it can be offered. The same truth emerges in regards psychological and spiritual suffering. We may be thrown into the crucible, but Văn believes he can offer his smile nonetheless.

The effort on his part is conscious: “Although there was not much joy in my smile, I nevertheless put into it all my good will” (Conv. 747). He can’t accomplish it without divine help, though, of course. The Conversations even end with Marcel saying that he himself “will make use of a smile to veil my sufferings,” while asking Jesus to give Mary a kiss from his “pretty lips” instead of him (Conv. 773). The Marian dimension is of great assistance: “As for me, I am very joyful; my mother Mary has carefully hidden my sadness, in such a way I can always keep my smile, in spite of great interior sufferings” (OWJ Jan 25, 1946). Marcel values every promise given by Jesus in this regard. He will be rendered beautiful in a transfigured way: “pinks cheeks, a charming face, shining eyes” (Conv. 177). This is figurative language, but it betokens something else too.

Lurking behind all this is that ubiquitous theme in Marcel’s writings, which I have tried to put to the side as much as possible in this post: “changing sadness into joy.” But we have to broach the topic eventually. Marcel writes an evocative letter to his spiritual director on the subject:

My heart has been full of sadness for a long time already but I do not always know if this sadness shows itself on my face, which leads me to think that even the good God cannot penetrate the sadness of my heart. Graciously pray so that I know how to change sadness into joy, and to offer this joy to my beloved little Jesus.

My smile, although having little value in itself, if it comes from a loving heart can only be bought at the price of infinite love. Pray so that in the border of my soul smiles of love will bloom in abundance which will charm the heart of my dear little friend. (To Father Antonio Boucher, 12 Feb 1950)

We can’t change sadness into joy and neglect the body. Charity needs to make its way down to our fingertips. Joy must break forth on our face. Marcel values the smile. We might also think of the brightness in someone’s eyes or the relaxed tightness of their upper cheeks near the eye sockets. Love must make itself physically real, and Marcel is aware that this is part of “changing sadness into joy.” Our entire investigation into transfiguration of the body could expand into this territory of spiritual resilience—spiritual resilience made physically manifest.

To get to transfiguration, then, has a cost. And that cost is high; “no beauty is acquired without passing through work and difficulty” (OWN6.14). Moral and ascetic work are entailed. Sometimes, even heroic charity is necessary, at least for some kinds of beauty. In this regard, there is nothing more unforgettable and haunting than the words of one of Marcel’s last letters, written from a communist concentration camp:

In prison, as in the Love of Jesus, nothing can take away from me the arm of love. No affliction is capable of wiping away the affectionate smile that I allow to appear habitually on my wasted face. And for whom is the caress of my smile if it is not for Jesus, the Beloved? (To Tế, 17 Nov 1955; cf. SH 39)[9]

[1] Marie-Joseph Le Guillou, Des êtres sont transfigurés. Pourquoi pas nous? (Paris: Parole et Silence, 2001).

[2] Ibid., 17.

[3] To = Marcel Van, Correspondence, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 3; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018).

[4] For Thérèse of Lisieux, references according to Œuvres complètes (Paris: Cerf / Desclée de Brouwer, 2023), with my own translations.

[5] STL = St Thérèse of Lisieux by Those who Knew Her, ed. Christopher O’mahony (Dublin: Veritas Publications, 1975).

[6] A = Marcel Van, Autobiography, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 1; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2019).

[7] Conv. = Marcel Van, Conversations, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 2; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2017).

[8] OW = Marcel Van, Other Writings, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 4; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018).

[9] SH = Father Antonio Boucher, Short History of Van (Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2017).