[ Marcel Văn and Clerical Abuse | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 ]

Throughout the month of November, I have published nine posts—which have really been articles—on Marcel Văn and clerical abuse. Starting from a summary, exhausting but not exhaustive, of the abuse itself (Part 1), then moving through how Văn’s primary mission of “changing suffering into joy” is actually the face of spiritual resilience in the wake of abuse (Part 2), but not neglecting the deep psychological need also for either rebellion or resistance (Part 3), I eventually discussed the effects of trauma (Part 4) and moral injury (Part 5, Part 6) in Văn’s life and death. Marcel’s intercession for priests (Part 7) and abuse victims and survivors (Part 8) formed a separate study, and in the end, I reassessed how everything I’d written about affects how we interpret Văn’s lived experience of Saint Thérèse’s Little Way (Part 9).

The point I want to make in this tenth and final article is the following. Văn is aware that he is preparing for the future. His biographers might be content to declare that the ecclesiastical systems in place were generally good and that abuses occurred “locally,”[1] or that “we must not generalize from particular cases. The river always carries trash.”[2] But Marcel himself is aware that he is just one piece of a larger puzzle.

In Marcel’s view, his experience isn’t unique. It’s not uncommon. After all, good priests “were scattered like grains from the paddy fields in a bowl of rice”—that is to say, few and far between and hard to pick out (OWV 808).[3] In charity, he tells us that he dares not generalize to everyone, for there were also many good priests, but unlike many of his own biographers, he stalwartly refuses to tidy things up with any language that downsizes the problem and denies that this is a full-blown crisis. Anyway, he can’t mention the good priests individually, he says, and his own mission is to call attention, in this world and the next—“I dare to affirm that after my death I will take myself to the seat of St. Peter to denounce [the culprits]”—to whatever makes “the light of faith founder in infernal darkness” (OWV 822–823). It is for this reason that he acknowledges that “there are many sentences in my account which may appear too harsh and lacking restraint,” which are really written with humility (OWV 822). It takes a lot for him to be confrontational. He does it regardless.

Since his task is, in this world and the next, to target abuses from priests and in clericalized settings, Marcel is undoubtedly an important piece in the divine plan. God has given him a mission in the universal Church. But he knows that he is only one piece. Other people have had and will have similar experiences. He speaks for them. He works for them. He prepares for them.

Văn also knows that he doesn’t take this task on himself. His life was tutored by the Providence of God. “It is God himself who has preordained all that I possess and all the events of my life,” writes Marcel in the final version of his autobiography (A 2).[4] There is a reason for his life. There is a reason for the things he went through. Ultimately, “Love knows how to choose crosses which are suitable for each soul” (Conv. 458),[5] and those choices are both entirely for the soul and also for the whole Body of Christ. Marcel eventually became aware that he might “serve as an intermediary between souls and divine grace” (A 3). Indeed, as he knows from his beloved spiritual sister Thérèse, the Body needs various parts (Ms B, 3r–5v)[6] and God deals with each flower according to the needs of the field (Ms A, 2v–4r).

Văn’s role was for his own time. It was also, he became convinced, for the future.

Apostles of Love

The one unavoidable characteristic of all Marcel’s ideas about the present and the future is that the endeavour must be apostolic. He isn’t called himself to a life outside the Church, and he isn’t to call people outside the evangelical fold. For everything he’s endured, his place is within the Church, and that Church, while being one, Catholic, and holy, is also apostolic.

Now, this doesn’t mean that Văn and those who come after him will be running around preaching the Gospel or actively ministering to abuse survivors. The apostolate of Văn is the apostolate of contemplative love.

Early on, Saint Thérèse had revealed to him that his will be “a hidden life where you will be an apostle by sacrifice and prayer” and that this will leave him “hidden in the heart of God in order to be the vital force of the missionary apostles” (A 651). Marcel understood the assignment. He would declare that he himself must “work in great secret” (Conv. 388). He professed, “I have buried myself in this monastery”—buried, hidden, almost unseen (To Father Louis Roy, 25 Jan 1949).[7] On one occasion, his language and imagery were almost lyrical, telling a friend that God “has manoeuvred skilfully to hide me behind a secret curtain, in the cage of his divine breast, to fill there the function of ‘heart,’ and become for priests a living force” (To Lãng, 22 Apr 1951). To be sure, he must be a living force not only for priests—but certainly for priests. Marcel intercedes where intercession is, in his personal experience, needed.

I don’t know if Văn had a conscious awareness of the remark of Saint John of the Cross that the smallest bit of pure contemplative love is more useful to the Church than all works put together (Spiritual Canticle 29.2).[8] It was a remark dear to Thérèse (Ms B, 4v; LT 221, 245; Pri 12). Still, whether or not he knows the reference, Marcel thinks this way. He knows that his spiritual big sister was to “be Love in the heart of the Church” (Ms B, 3r–4v). He understands the value of a hidden life of contemplation united to the little work of Nazareth. His role is essentially like this; it is to “deliver myself entirely to your Love”—“an eternal love, without end, without measure, and which no tongue can perfectly express” (Conv. 331). From that flows Marcel’s usefulness.

Marcel, however, did not stop there. The Conversations record Jesus telling him that he is only one of many, and the many must come from all over and all types:

Why do I have to choose many apostles for the expansion of the reign of my Love? Because it is necessary that there should be some for every category of person. You, for example, you must use a certain manner of speaking, while another will have to use a different one, which responds to the feelings of his audience. It is the same for crosses, for sufferings; I must choose different crosses for each soul to whom I send them, since, if I dealt with all souls in the same way, who would be able to walk along the path of perfection? (Conv. 512)

While Marcel’s Nazareth was the monasteries of the Redemptorists in Vietnam, then the internment camps of the communists, there will be other Nazareths and perhaps even ways of life that seem less like Nazareth, with less manual work and more intellectual, with less hiddenness and more visibility. But still, the same truths will be lived there, Marcel thinks, in the midst of whatever is happening and whatever the personality. There is a need for this contemplative love to be incarnated everywhere and every time.

The future movement of the apostles of Love

Marcel’s role in all this is something like the vanguard. He has, if I may say so, the spirit of a founder. Of course, he has nothing of the ability to make that founder’s spirit active and effective. He’s weak. He’s wounded. He’s small. Absolutely, he could never be a founder of a new religious movement. But that doesn’t mean his heart isn’t built that way. He has all the ideas and the explosive force of contemplative love that a founder would have. His lack of material, physical, and psychological means doesn’t change that in the slightest.

Passages displaying the spirit of the founder are numerous. The most common form that this exigency comes out is in a demand to pray for the apostles of Love that are to come. Văn doesn’t only pray for priests (Part 7) and abuse victims and survivors (Part 8). He also intercedes for some future movement identified as “apostles of Love.” For instance, Mary implores him:

I love you dearly, my little one, and you, you must pray really hard for the apostles of my reign… Listen to me. As Jesus told you, at the beginning of the battle, my apostles will appear very weak, so weak that one will believe them unable to face up to hell… But, my child, for what reason will my apostles be allowed to submit to this humiliation because of me? I will have to allow it for a certain time so that my apostles will learn to be more humble… However, my child, the more the devil is victorious in the beginning, the more he will be shamed afterwards. It will no longer be me in person who will crush the head of Satan; but I shall be happy to let my children accomplish this work on my behalf. Seeing me use my weak children as many feet to crush his head, Satan will be completely disgraced… (Conv. 254–255)

Marcel’s role is to “pray, pray a lot” (Conv. 255, 256, 263), including for “future priests” to have “hearts full of courage and zeal” (Conv. 256). He is to pray in several ways. “Prayer of the will, prayer of works, prayer of feeling,” urges Mary (Conv. 260). “Pray with words, pray with your sighs, pray with your desires. Of these three ways of praying you will be able to use the latter two more easily,” she assures him (Conv. 256). This is for a future army of apostles of Love “in all countries and in every country” (Conv. 262).

But who these apostles are to be, Marcel has no idea! He conjectures it might be little children, but plainly admits this is “only surmising” (Conv. 343). As usual, he doesn’t quite get, I think, the whole scope of what makes him little, what makes him weak, what sends him to a spiritual realm of childhood. Those exigencies come in part from his trauma and other “after-effects of the sickness of my soul” (A 533) that leave him “ill with the anxiety which imprisoned my life in a narrow, parched setting” (A 532) (cf. Part 4, Part 9).

These apostles of Love will be people who are weak like him. Maybe they suffered abuse. Maybe they endured moral injury at a distance. Maybe all this was endured at the hands of priests or in a clericalized setting. Maybe it happened elsewhere. All such survivors—and of course many other classes of people besides—fit perfectly into his army of apostles of Love. The only qualifications needed seem to be to be little, to love, and to walk the Little Way in Nazareth.

The first unfulfilled dream

So far, so good. Things are about to get very messy. I feel I need to touch on passages in Marcel’s correspondence that other biographers and scholars don’t dare touch with a ten-foot pole.

Marcel has two big unfulfilled dreams, and the way he presents them makes it really hard to appreciate their value. I stress that these ideas are vague and nebulous. Both of these ideas are considered by Marcel as “something heard in a dream, since I think that it does not exist in reality” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 9 Oct 1950). Yet he also—and this is what makes these passages radioactive to biographers and scholars—talks about them as some kind of divine inspiration or revelation.

The fact of the matter is, Marcel was not particularly great at separating his own psychological contributions to his spiritual life from those which came directly from God. Now, personally, I don’t doubt that he received a lot directly from God. But whether these things were spiritual or intellectual visions, or locutions in any technical sense, or just impressions filtered through psychological material already present—this is hard to say anything about, because for all his innate intuitiveness, Văn seems to have been sorely lacking in the self-critical introspective domain. God used that, I’m sure. We wouldn’t have the Conversations, for example, without that kind of inbuilt naivety. But at times, this makes interpretation complicated.

This is one of those times.

Two letters written from Saigon detail Marcel’s two unfulfilled dreams (To Father Antonio Boucher, 29 Sep 1950; To Father Antonio Boucher, 9 Oct 1950). The first of these letters mentions the things Marcel receives, maybe uncritically, in prayer. The second consists of a bit of a backtrack. Marcel isn’t saying that these were exact revelations. They were more like impressions in a dream, but that characteristic of them doesn’t deter him from answering the questions of his director of conscience, going full-steam ahead, and elaborating anyway.

The first dream is sparked by inadequacies of foreign missionary priests from France (i.e., the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris/MEP). Marcel says that Jesus “reproaches many members of the Society for having profited from their life as a missionary for allowing themselves numerous abuses.” For this reason, a group that he calls “auxiliary missionaries” (trợ thừa sai) is necessary. These auxiliaries should be catechists to assist missionary priests, Marcel writes.

This, I think, is an interesting dream. In Marcel’s world, catechists are the bad guys. They are “beyond all limits” (OWV 808–809). To be sure, they’re not completely bad. But they’re almost always bad apples, and the bad apples spoil the whole barrel—or as Văn would say, “A single worm suffices to destroy a whole bowl of soup” (OWV 850). Marcel doesn’t leave us in doubt about catechists: “As for the catechists, one has never seen a single one keep perfectly the rules imposed… If the pillars and the rafters, essential parts of the building, are so weak, how can this building, built by the first missionaries at the cost of their sweat and blood, last?” (OWV 815) Their virtue is questionable, and the rot is widespread. Yet for some reason, Marcel envisions catechists who will somehow make up for the deficiencies and abuses of priests.

This is an intriguing proposal, and I doubt it was ever realized in exactly the form that Marcel imagines and that he says one Monsignor Khuê was seeking to found. War overtook Vietnam very shortly afterward, and the North–South division changed local dynamics for the next decades. At any rate, I think Marcel’s own commitment to the idea can’t be separated from his second unfulfilled dream.

The second unfulfilled dream

The second unfulfilled dream is called “the missionary Virgin” (đừc mẹ thủa sai). This, in Marcel’s interpretation of the dream, was to be a community of women who “will keep the silence of a dumb person, whilst working in the middle of a tumult of voices” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 29 Sep 1950). Marcel understands the first member of this community to be his own elder sister Lê, and he is frankly “stupefied” at this. Indeed, he is “horrified” that he may be deceived in thinking so and in attributing anything supernatural to his dream.

In his two letters to his spiritual director, Marcel even describes the habit worn by the community members. It mixes light and dark and combines Carmelite and Redemptorist features. We’re even told that there are sandals and no socks. Personally, this is where I start to think that things are not as they seem. Are we not talking about a highly symbolic register? Light and dark are symbolic. A merging of features from Thérèse’s community and Marcel’s can’t be without meaning. Even socks mean something spiritual to Marcel; they’re a sign of the sacrifice of self-care when it’s needed, and a lack of socks could indicate a variety of things, such as no personal need for intense self-care, unconcern about varieties of religious practice, or just someone who isn’t sick or currently prone to become sick (cf. Part 9). I really don’t think Marcel was given a vision of what kind of exact habit these women were supposed to wear. I’m not even convinced they get a habit for any other reason than to communicate symbolic truths.

At any rate, Marcel sees just one woman in his dream. He describes her style of life as well:

Her activities hardly resembled at all those of communities already existence in Vietnam. She consecrated half the day in the cloister to prayer and to the recitation of the divine office. During the other half she devoted herself outside to apostolic works. Her “interior” programme differed in no way from that of a Carmelite. When she received visitors she did so behind a violet veil and behind an iron grill … etc.

Her external activities: Normally, when she arrived at a village, all the young girls would run to her at the crossroads and wave to her. But she she was happy to give them, as sweets pulled from her bag, copies of the catechism. She was so joyful and good that the children were pleased to be close to her. She never chatted or joked with people on her route but walked seriously, her face veiled in spite of all the mocking directed towards her. As soon as she crossed the door of the house she lifted her veil.

In the house she accommodated also many young girls, but solely outside the cloister. She was the only one to walk around the interior where no one was able to enter. She taught the children many subjects, but her special subject was the teaching of religion. She, herself, prepared their meals and washed their dishes. When she did manual work she did not wear her black cloak, but at the end of the work, she put it on again to go and kneel before the tabernacle, and she wore it all the time when she went out on the road …etc. I cannot summarise in this letter all that Jesus made me see. He said to me: “This religious is like a dumb person in the middle of the noise of conversations, she hears with her ears but not a word escapes from her mouth.” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 9 Oct 1950)

This all seems very detailed. At the same time, it strikes me, just like the described habit, as incredibly symbolic. This person has a specific time of prayer. She has specific prayer practices, and they are contemplative in orientation. Yet she also works in the world, without habit, and mingles in the world. It is there that she meets children, though why these children need her help but not anything like lodging is a question that Marcel doesn’t seem to ask. Most children don’t need the kind of care Marcel describes, and if they do, they’d often benefit from an orphanage or similar, too. But this isn’t on offer from the woman Marcel dreams of.

No matter—Marcel interprets literally. He thinks this is an actual future religious community to call into existence. When Lê marries, he realizes immediately that this community can never exist exactly as in his dream. He finds himself “feeling a great coldness” (OWN2.32). He is naturally “troubled,” “afflicted,” and “discouraged” about the subject of his vision, dream, or imagining (To Father Antonio Boucher, 6 Jan 1952).

Yet, as I have insisted, Marcel is clearly reading everything hyper-literally. He sees someone who is Lê. Well, who is Lê? What would she represent to his imagination? She is a particular person he knows. She is his sibling, yes. But in terms of his symbolic imagination, she is not the older brother (Liệt) who developed a disability at the onset of adolescence, nor for that matter the younger brother (Lục) who was born with a disability and a very weak character (cf., e.g., OWN3.40). Nor is she Tế, the younger sister who opts for cloistered life as a Redemptoristine nun (as Marcel had foreseen—cf. Conv. 66; OWN2.49).

Lê is the person for whom Marcel had not long before half-invented a quasi-religious life in the world. He suggested to her “a hidden life, an ordinary life like that lived by most people,” which could be lived provided we set about “offering” our life to God and make an effort to “consult each other” spiritually (To Lê, 18 May 1950). He says this to her, even though he is troubled that she “has lost her simplicity and her frankness” (Conv. 743). Why does he say so? Because she “often” undertakes “visits the parish priests and catechists” who say and do inappropriate things—something Văn’s mother hasn’t yet perceived as injurious, herself too being deluded about the lives of the priests and catechists (Conv. 744). This, in Marcel’s memory bank, is the religious content of what is sitting there along with his elder sister’s name.

And lo and behold! If one just takes children as a symbolic substitute for the souls of abuse survivors, does Marcel’s dream really seem so incredible? The person he sees used to get along with the priests and catechists who are abusers. She gives this up. She lives a life in the world still. At home, all is contemplative. Her vocation is to contemplative prayer, with all its implications of offering, intercession, and sacrifice, one would assume. After all, Marcel foresees a home life not at all differing from that of a Carmelite, and he knows from Thérèse that the purpose of the reformed Carmel was to intercede for priests who are not “purer than crystal” (Ms A, 56r).

In the streets, meanwhile, this woman mingles with all the noise. But she doesn’t participate in the noise. Her goal is to be there for the “children”—let’s say the abuse survivors (cf. Part 4). They don’t enter her innermost cloister. The part for contemplation remains. Yet she is all for them materially—even spoiling them and letting them have the version of the Little Way after abuse (cf. Part 9). She is all for them with her ear and with her words—which are religious and not secular, that is, offering healing in the realm of the spirit, never usurping the role of other healing needs.

Marcel says one half of the day was contemplative life and the other “apostolic works” outside—but does this woman of the dream really have an active apostolate? The “children” come to her. She goes out and about. She visits Jesus in the tabernacle. Marcel says nothing of an active, planned apostolate to these “children,” aside from listening, and cooking, and washing up, and providing a few treats and delights here and there. But it isn’t some massive organization, nor even a small one. It’s just the obvious answers to immediate needs where she happens to be—walking, at home, in the chapel or church. Nothing that Marcel describes is structured. It remains a contemplative life at the core, but with a spreading, radiating influence. She is a contemplative, but she goes out. The “children” are drawn in. She responds on the spot. She goes home to her inner contemplative sanctuary and back to prayer and intercessory sacrifices.

It seems clear to me that Marcel has no models to draw on here, and I would suggest that the closest models that would fit his idea incarnated in religious life would be the Little Sisters of Jesus: contemplative, tabernacle, working outside the cloister (i.e., without the habit), a ministry of presence and hospitality. Marcel wants a kind of Nazareth spirituality.

I don’t think, however, that a religious life is necessary to fulfilling this dream. Marcel mentions nothing about a community; the woman is alone. He says nothing about the three vows of professed religious life. In fact, Lê marries. The symbol of this dream is a layperson. She’s the layperson for whom he had even earlier suggested ways to live a Nazareth spirituality as a layperson.

I’d say the dream is ambiguous. It could manifest in an arm of professed religious like the Little Sisters of Jesus (or Little Brothers of Jesus), but whose ministry of presence and hospitality is extended to and focused on the “children,” the abuse survivors. Somehow, they have a presence to these little ones, rather than the workers, the poor, and those geographically marginalized. The ministry has shifted to be a contemplative presence to the “children.” On the other hand, the dream could be instantiated somehow among laypeople, exercising the same ministry of presence but within the lay state.

Possibilities

It is really easy to just dismiss Marcel’s two unfulfilled dreams as a product of his difficult years at Saigon. We know that this was a period of renewed experience of abuse, and the little brother started to spin out (cf. Part 1). Being deceived in his prayer life, and expressing these deceptions only to his spiritual director and no one else, is hardly a serious offence under the circumstances. In fact, it’s pretty mild on the scale of things we could get wrong about prayer.

I don’t want to do that, though. I’d rather see something of value in these two unfulfilled dreams. Marcel is hyper-literalistic about them, but it seems far better to me to see the dreams as unconscious longings that express something about Marcel’s preparation for the future. In the first dream, the ranks of the catechists—those nefarious, abusive characters of the Autobiography—are filled with apostles of Love, coming to the aid of abusive priests. In the second dream, a Nazareth-like spirituality is lived by either a religious community or a layperson, offering a ministry of presence to “children,” who are manifestly symbols of abuse survivors in Marcel’s imagination. The professed religious or layperson herself used to consort with wayward priests and catechists as if nothing was wrong with their behaviour and all the coverups of it—but she was called out of that and found a new life.

I’d say this fills out the profile of the apostles of Love nicely.

I’ve previously written about my own dream. I don’t think it is the only way to live out the mission of being an apostle of Love and to realize Marcel’s two unfulfilled dreams at the same time. But I do think that my dream is one possible way.

Faithful to Văn’s own call to be a “hidden apostle of Love,” I dream that there could exist some sort of network of contemplative prayer.

Faithful to the inclinations of Văn’s heart, this contemplative prayer would be Eucharistic and preferably, when possible, be offered before the tabernacle, not monstrance.

Faithful to Văn’s identification with the Little Way, prayer and sacrifice would be simple and small. For survivors themselves, it would be the Little Way made yet smaller (cf. Part 9). It would take in the demands of resilience (Part 2), rebellion/resistance (Part 3), trauma (Part 4), moral injury (Part 5, Part 6), and whatever other psychological phenomena of abuse survival we become aware of in the future.

Faithful to Văn’s status as a survivor, the prayer would be in union with and offered for abuse victims of all kinds within the Church (clerical abuse broadly considered, including that committed by priests, catechists, religious, and teachers in an officially religious environment, primarily Catholic but ecumenical in scope when the person praying has personal connections) and in support of those who have an active ministry to the survivors (Part 8). It would also do the necessary work of praying for priests, fully aware of the status Văn gives to that requirement and the weight he places on the horror of abuse (Part 7).

And I don’t think this can be a primarily cloistered thing, because that smacks of removing oneself from the problem. Faithful to Văn’s attachment to the mystery of Nazareth, I dream that the people of this movement would be immersed in the lives of others. Whether laypeople or professed religious, they would live like everyone else. They would offer this contemplative prayer immediately before and after Mass times, for say a quarter or half an hour each side. Somehow, even though largely silent, they would be visibly approachable, in some simple way marked and designated, within the parish setting, for anyone to talk to, so that people know, really know, that they can speak the truth and that this person is somehow vowed to listen to, honour, pray for, and offer sacrifices for victims and survivors.

And I would also dream that, wherever this ministry of presence, availability, and prayer is offered, it is offered with the knowledge and approval of the priest and/or bishop/ordinary, so that, even though clerical authority figures cannot be the visible touchstone of this prayer, availability, and presence (for this would render the contact inaccessible for too many survivors), they too are nonetheless offering their commitment to it.

Wouldn’t this realize the mission to be an apostle of Love and to enact the substance of Marcel’s two unfulfilled dreams?

How different would the Church be if such a dream were brought to life! Every Eucharist would remain intact. Nothing within the confines of the Mass would change. Nobody would need to alter anything. But still, everything would be transformed, if you paid enough attention. The gathering of the community would be surrounded by a relatively silent, but partly visible, ministry of presence to, availability to, and prayer for abuse victims and survivors. It would be configured by a preferential option for those abused in a clericalized setting or by a clericalized person. And this would become known. It would become lived. The acts would be small. They would be Nazareth. Nothing would stray from the Little Way. But it would nonetheless amount to a spiritual revolution. We would have the same Church, but a new Church.

Like my dear Văn who has done so much for me, I dream, I dream, I dream. The only question that remains is: Can it be done?

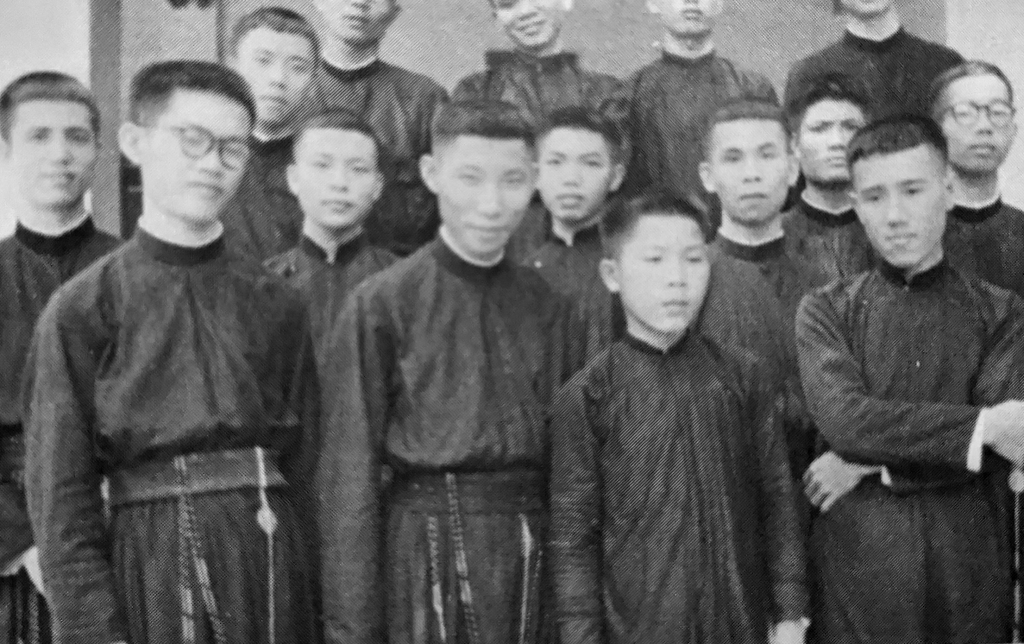

Image in header: Marcel with Redemptorist coadjutor brothers, ca. 1950

[1] Charles Bolduc, Frère Marcel Van (1928-1959). Un familier de Thérèse de Lisieux (Montreal/Paris: Éditions Paulines & Médiaspaul, 1986), 22. This assessment is quoted favourably by Marie-Michel, L’amour ne peut mourir. Vie de Marcel Van (Paris: Fayard, 1990), 74. The author of this latter book, however, was recently removed from the clerical state by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (cf. this communiqué of the Diocese of Valence regarding Marie-Michel Hostalier), for sexual abuse against adults (cf. “Le Père Marie-Michel Hostalier renvoyé de l’état clérical,” cath.ch, 16 Sep 2021). I think the facts speak for themselves, though we certainly need a greater appreciation for the deviated understanding of Văn’s life that has been generated by having a canonically disciplined abuser controlling the narrative of the life of an abuse survivor.

[2] Marie-Michel, L’amour ne peut mourir, 64. The author (on whom see the previous footnote) is of course perfectly capable of drawing attention to “the millions of kids worldwide who are exploited, beaten, prostituted, sold, rejected” (ibid., 114). It is only the scope of clerical abuse that is minimized.

[3] OW = Marcel Van, Other Writings, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 4; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018). Additional system for abbreviations explained on page 14, e.g., OWN = notebooks; OWV = various writings.

[4] A = Marcel Van, Autobiography, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 1; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2019).

[5] Conv. = Marcel Van, Conversations, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 2; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2017).

[6] All references to Saint Thérèse of Lisieux using the system in Œuvres complètes (Paris: Cerf / Desclée de Brouwer, 2023), with translations my own.

[7] To = Marcel Van, Correspondence, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 3; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018).

[8] The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, 3rd ed., trans. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 2017), 587. I am not the only one to highlight this sanjuanist text in the context of Văn’s dispositions: see the testimony of a young adult named Muriel in Marie-Michel, L’amour ne peut mourir, 243.