[ Marcel Văn and Clerical Abuse | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 ]

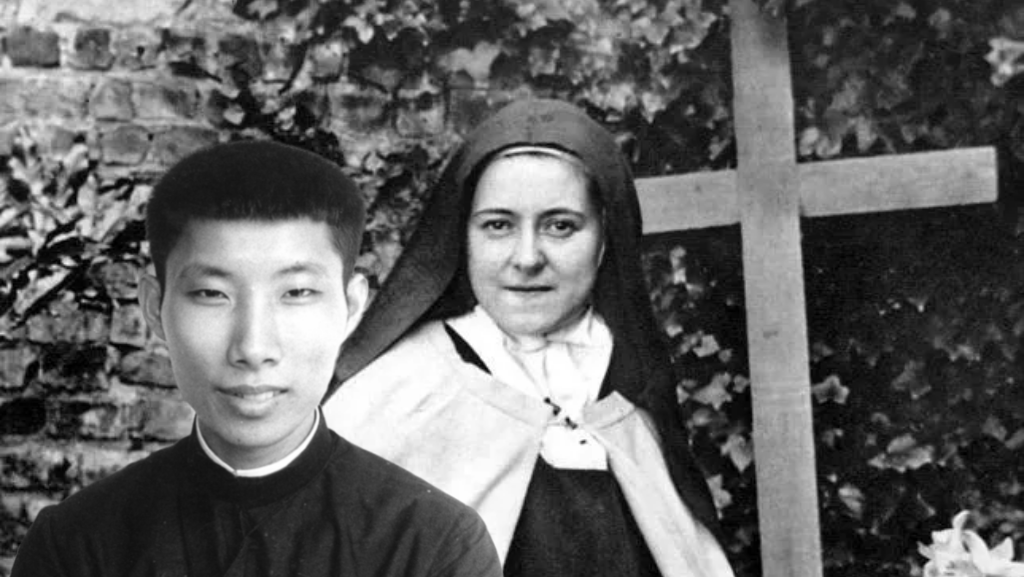

Nobody doubts that Marcel Văn saw himself as a spiritual little brother of Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face. It’s pretty hard to miss. Thus, we find biographers speaking of a “life placed under the aegis of the ‘Little Flower’,” or “a sort of ideal double of himself” found by Văn in Story of a Soul, indeed the realization of “unconscious aspirations” in an “effort of identification with her model” and “emulation” of Thérèse, Marcel’s “inspiration and animator,” in his “conscious life.” Apparently, you can pack all that kind of language pretty densely in a published book. I took it all from the same page of the earliest biography.[1]

It is true that Văn is one petal of the Little Flower (To Father Antonio Boucher, 14 Apr 1950; To Pope Pius XII, 4 May 1950).[2] It is true, as he points out in explaining this very title, that “the petal is of the same flower, it has the same colour and exudes the same scent” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 4 May 1950). He is a second Thérèse (Conv. 108, 251)[3]—or part of her Little Way. Marcel is right to point out his surroundings; he is a petal that fell and is carried by the wind (To his mother, 18 May 1950), finding a place in the shade of a bamboo tree (A 7–8).[4] The shade of a bamboo tree can mean for Văn solitude (To Tế , 21 Apr 1951). But it’s also plainly an allusion to his ethnicity, his location, his culture. As a second Thérèse, he is a Vietnamese one.

Yet, this is not all. This petal is also something else than an instantiation or part of the Little Way shaded by a bamboo tree. It is a detached petal, as Marcel says (A 7; To Tế, 22 Apr 1950). It’s fragile and fragmented (OWN2.30).[5] It’s fallen off (OWN2.50). It’s broken off. It’s, let’s be honest, ripped at the edge, broken. Fallen to the ground, it’s trod upon (OWV 904). It’s a piece of the Little Flower for survivors of clerical abuse. Marcel is more than this—absolutely. But he is also exactly this.

Psychological backgrounds

Let me say very simply that the particular psychological journey of Văn in no way compromises his adherence to the Little Way. If we were to call into question the supernatural status of the Little Way in Văn just because he is a survivor of clerical abuse, we would, if we remained even-handed, also have to call into question the discovery of the Little Way by the Little Flower herself.

Thérèse’s childhood, like Văn’s, starts with her as a little, immensely mischievous “elf” (lutin) (Ms A, 4v, 8r, 10v, 24r).[6] She receives, then, a series of shocks that send her into “the crucible” (Ms A, 3r, 12r, 27r): the death of her mother, which causes her to declare that her elder sister Pauline will now be her mother (Ms A, 13r, 17r); then, suffering away from the family foyer at school (Ms A, 22r); after that, enduring the quickly chosen, brutally felt option of her “second mother” Pauline for the Carmel and her departure (Ms A, 13r, 25v–27r, 41r–41v). It takes no genius to find in these events the psychological problem of rejection and abandonment in childhood. In the aftermath, Thérèse suffers some sort of nervous, psychological reaction and trial, including hallucinations, a “strange sickness” (Ms A, 28v) which she attributes to the demonic (Ms A, 27r, 28v) and for which no medical solution is found (Ms A, 27v–28r); the only cure to be gained came by a miraculous holy smile from the Blessed Virgin (Ms A, 30r, 35v) and was reinforced by her first receptions of the Eucharist (Ms A, 35r–36v). During this time, Thérèse gets close to Marie as a new second mother (Ms A, 41r)—then comes the shock of her departure for Carmel (Ms A, 42v–43v). Things are not as bad the second time. But the psychological wounds persist and threaten. There is no “complete conversion,” no complete healing until the famous grace of Christmas 1886 (Ms A, 45r). It is here that the “race of a giant” (Ms A, 44v) took hold and, as the editors of the latest edition of the Œuvres complètes suggest, it was from this point that Thérèse later “relaunched” her great trajectory.[7] Of course it is when we find ourselves totally little and totally dependent that “confidence and nothing but confidence” (LT 197) is able to find a foothold.

It is plain that Thérèse finds her way—and her Way—amid the experience of events at a psychological level, a series of psychological wounds that disrupt the development of her personality. Her particular series of shocks is, I would argue, quite typical of the modern world. They occur within a relatively stable family and society. They would be the matter for the contemporary modern psychologists. Loss of maternal figures sounds right up the alley of the great psychological prophets of modernity, particularly Freud. In contrast, Văn’s psychological eviscerations, particularly those related to the clerical abuse that challenges so much of the foundation of our social relationships, are arguably much more representative of a postmodern world, with its continual social dislocations. But that is in all the relevant ways here a distinction without a difference. Psychological conditioning of a grace event is psychological conditioning of a grace event, whether in Alençon-Lisieux or from Hữu Bằng to Quang Uyên. We would be hard-pressed to keep the supernatural power of the Little Way in one case but not the other. Modern world or postmodern: how does it matter? Surely it shows the rapprochement between Văn and Thérèse more than a separation. And in short, there is nothing about psychological conditioning of events that makes the Little Way less the Little Way. In historical terms, it’s exactly the opposite: Thérèse had her own psychological conditioning that led to the discovery.

So, when I talk of the Little Way after clerical abuse, I mean the same Little Way. I just mean it takes on particular form, particular origins, and indeed particular urgency. But it is the same underlying universal Way. Văn knows “a very straight, very short little way” (Ms C, 2v). After all, it is only Jesus himself who is “the most direct path leading to perfection” (OWN3.33). He is that “very short little way,” which is not really “a brand new way,” as Thérèse herself calls it (Ms C, 2v), but rather, as Marcel gently corrects her, just “the way of perfection that the saints of former days have followed” (OWD6). Marcel seems to have in mind something like what Pope Saint John Paul II did, when he called Thérèse’s way “unique” yet also “the fundamental mystery, the reality of the Gospel” and “the confirmation and renewal of the most basic and most universal truth” (Divini Amoris Scientia 10). Not really “brand new” at the core, say some of Thérèse’s biggest fans, Văn among them. Of course, despite these minor disputes, Marcel declares he has “the same mission” as Thérèse (OWN2.50). He doesn’t know another one. His Little Way is hers. That’s vitally important.

Why Văn?

What exactly is it that makes Marcel Văn into a model of the Little Way of Saint Thérèse? Is it because the saint appeared to him and taught him? Is it because he studied Story of a Soul so assiduously? Is it his physical weakness?

If we take Văn’s own writing as the standard of judgment, the answer to each of these proposals is evidently “no.” In the Conversations, Marcel repeatedly tries out all these options. And they are rebuffed by his heavenly friends. To be sure, the last one has a grain of truth to it. Although his beloved Thérèse had declared herself the smallest of souls (Ms B, 1v, 3r) and weakness itself (Ms C, 15r; LT 79), Marcel is told that he is “weaker than the saints, your brothers and sisters” (Conv. 22). Jesus even says to Marcel, “I have never seen a soul weaker than yours” (Conv. 235; cf. 458, 530). And Mary says to him, “I love you and I have pity on you more than I love and take pity for little Jesus” (Conv. 248), presumably because of Văn’s great weakness. Văn is apparently that impossibility of Thérèse: a soul weaker than hers, smaller than hers, which God would thus be pleased to fill with even greater favours still, should it but have full confidence in his infinite mercy (Ms B, 5v).

If we wanted just a single example to illustrate that Văn might be a weaker soul than his spiritual big sister, I would suggest looking at how they sleep. In the Conversations, Marcel recounts “the only time that I succeeded in sleeping well without having any terrifying dream” (Conv. 760). Although he does occasionally note gentler dreams (e.g., OWN2.34–35), he lives with nightmares. This is in stark contrast to the dreams of Thérèse, which are typically of forests, flowers, streams, the sea, and children (Ms A, 79r). Even when she has a dream with devils in it, the mere gaze of a child in grace is enough to send them packing (Ms A, 10v). Of course, she probably had some exceptions to the rule. But with her and Marcel, the rules and exceptions are reversed. Văn is weaker than Thérèse. When Jesus and Mary say this to Marcel, I think it is not exactly unbelievable.

But it would be wrong to think that this great weakness is explained by the frailty of his body. When he suggests as much, Jesus replies directly but lovingly, “Not only are you weak but also you know nothing of your weakness” (Conv. 235). Marcel doesn’t get it. He just doesn’t. And that’s okay. It is for his spiritual director and those who come after him to understand. He can just live the weakness, and that will make Jesus happy. Marcel’s inability to understand is a leitmotif of the Conversations (starting from Conv. 13 onwards) and gives him persistent consternation (e.g., Conv. 427).

What I hope I have shown beyond a shadow of a doubt in this long series of articles is that Văn’s own weakness is—at least in part, but a large part—down to being a survivor of clerical abuse. Clerical abuse affects all the main aspects of his spirituality. And of course Văn doesn’t have words or a concept for that influence. Of course only people to outlive him or come after him will understand. His abuse happened in the 1930s. He lived only until the ’50s. It would take impressive foresight and conceptual skills to parse that abuse and its consequences out from his experience exactly as such and in all its implications. And while Văn was highly intuitive and innately intelligent, he wasn’t highly rational or highly educated. As regards the deep wound that cut him down, he just didn’t get it at a rational level. He only lived through it with all the right dispositions.

But that doesn’t mean that Marcel Văn isn’t the guide par excellence for a contemplative spirituality for survivors of clerical abuse. Quite the contrary. Despite his lack of rational and conceptual understanding of his own life, he was sufficiently open to the workings of God to have established the foundations for an entire mode of being Christian. He has, oddly, the spirit of a founder. But he lacks the intellectual means, both internal and external, to make it happen—and that is part of his weakness, too, which God in his infinite mercy was willing to use.

Văn is, “following the example of little Thérèse of the Child Jesus… the holocaust victim offered in love” that “little Jesus will accept” (Conv. 248; cf. Ms A, 84r; Ms B, 3v; Pri 6). Indeed, he says the same: “No matter in what direction I look, I see only crosses, nothing but crosses” (Conv. 315). This transformation into a victim of Love allows Marcel to create something new—as old as the Gospel, as old as the Little Way, but truly new.

Basic aspects of the Little Way in Văn

Despite living a half-century and half a world apart, Thérèse and Văn tell a lot of the same story. There are even superficial resemblances, such as that both the Little Flower and her Petal receive an important grace at Christmas (Ms A 45v–46v; A 436–439), or like when Thérèse receives a little flower from her father and understands God’s care for it as akin to his care for her (Ms A, 50v) and a kindly priest giving such a little flower, marked with a dewy tear, to Văn, but him not yet understanding what the priest means (A 530–531). But we should be clear and emphatic that these are not enough to establish the same Little Way.

You can’t have the Little Way without weakness. The whole point of it is that we discover our own weakness and leap into the arms of God the Father—or rather, realize that God is always already there waiting to pick us up. We can’t do it ourselves. God will do it for us. As Marcel says, “I am happy, and this happiness, which is a great comfort for me, consists in the fact that my heavenly Father understands that I am a weak and destitute soul”—words which Marcel properly acknowledges to be “borrowed” from Saint Thérèse (To Tế, 15 Aug 1946).

Like Thérèse (Ms C, 2v), Văn often looked at the examples of saints and thought this was not accessible to him (A 72, 562, 567–570; SH 19).[8] She, of course, jumped to the conclusion that God did not give her a desire for sanctity that was unrealizable. Văn, for his part, was relieved when he found this approach in her. From that moment on, his trajectory was fixed. His spiritual big sister knew that “because I am small and weak, he lowered himself to me, he instructed me in secret about the matters of his love” (Ms A, 49r). Marcel, for his part, hears Jesus tell him that “a single glance of your weakness suffices to charm my Love and to draw my heart to you” (Conv. 374).

We can find, then, a lot of the same vocabulary and imagery in Marcel as in his spiritual big sister. It is said by both that the arms of Jesus are the elevator taking us to the heights (Conv. 408; To Father Antonio Boucher, 27 Jun 1952; cf. Ms A, 32r; Ms C, 3r; LT 229, 258). Marcel knows that they show forth the incompréhensible condescendance of God (Ms A, 72v), his ineffable condescendance (Ms B, 5v). He, apparently conscious that the elevator was a newfangled invention in Thérèse’s day, sometimes adapts the image to something almost as modern in his own day, the airplane (e.g., Conv. 38; OWN2.55–56).

At other times, Marcel adapts the language to his own circumstances. He is young. His voice is breaking. This introduces a new difficulty. When he goes to sing, he says, “I cannot reach the high notes.” This, translated into spiritual meaning, tells us that “it is impossible for you to ascend to God if God does not himself draw you to him” (Conv. 114). There is a simple spiritual message of spiritual childhood even when we discover that we are leaving physical childhood.

Speaking of spiritual childhood, it is not clear if Marcel has perceived that this is a term which doesn’t actually occur, as such, in Thérèse. But he uses it himself. He adds, though, by preference, an explanation of what this means. What he describes as “the way of childhood” is also “the way of ‘Love and total abandon’” (To Father Antonio Boucher, 27 Jun 1952). Jesus tells him that it is “sufficient” to continue “loving me and abandoning yourself to me in total confidence,” as “your sister Thérèse has already taught you” (Conv. 429). The conjunction of “love” and “abandon” (cf. Ms A, 83r) or “love and “confidence” (Ms A, 80v; Ms C, 36v–37r; LT 226, 258, 261) are Theresian commonplaces. Marcel has got that right.

Marcel is pretty evangelical about all this. He spreads the message. He treats it simply. He proposes it to others. The most basic aspect for him is that everything is proportional to our own abilities. For example, he writes to his younger sister:

Formerly, before her entry into religion, little Thérèse devoted herself to making only like sacrifices, for example: renouncing her own will to follow the will of others in things which were not bad; not to say such or such a word which could hurt others… etc. My sole intention is to counsel you to do the same thing, since before her death little Thérèse affirmed that the mortifications he had made could be made in the same way by all little souls. (To Tế, 20 Oct 1946)

The period Marcel primarily references here is the three months Thérèse had to wait before entry into the monastery, the period of sacrifices that were “nothings” (Ms A, 67v), but it is not something exclusive to that short section of the autobiography, for elsewhere she speaks of “the means of being holy by fidelity to the smallest things” (Ms A, 33r) and even in Carmel the same kinds of acts reappear as “little virtues” (Ms A, 74v–75r), “hidden and ordinary virtues” (Ms A, 78r), and “little sacrifices” (Ms B, 4r; Ms C, 31r). When talking to his own little sister, Marcel perhaps systematizes a bit more than his spiritual big sister. But it’s all there regardless.

The basic message here is, as Thérèse teaches, that nothing is impossible to Love. This is true in the first place of our own motive, but it is also true as to the value God sees in our actions:

Love can do everything; the most impossible things do not seem difficult to it. Jesus does not look so much at the greatness of our actions nor even at their difficulty, but rather on the love that causes these acts to be done. (LT 65, indirectly quoting Teresa of Avila, Interior Castle 7.4.15; cf. Ms C, 28v; LT 191)

Marcel also tells us that love is what counts:

Love is always the power behind action. Do not distinguish between that which is elevated or humble, big or small, that is a more important mortification than to wear a hair shirt or give oneself the discipline. (OWN1.60–61)

For examples of “a few small mortifications” Marcel suggests “to put up with thirst sometimes, to eat without adding any condiments, (brine), etc.” (OWN 9.23). Sometimes, however, the Flower and the Petal share particular examples when talking about small actions. Suffice it to list one parallel. Thérèse writes to Léonie, “To pick up a pin for the sake of love can convert a soul” (LT 164). Marcel, for his part, writes in a notebook, “To spare a minute picking up a needle through duty and charity is more meritorious than spending a whole year’s work dedicated to writing a book in defence of the faith” (OWN2.26). This brings us to the next theme, which is major in Văn: not only is love what counts, but its effects propagate through prayer and the communion of saints.

Love can do everything

Like Thérèse, Văn is confident not just about God saving him in his littleness, but in God using his littleness to save others. These little sacrifices committed with total confidence in divine Love are enough to make changes in this world for other people. Marcel is explicit: “if anyone really has confidence in Love, he will obtain from it all he wishes” (Conv. 444). This echoes Thérèse, who, satisfied with her aridity, “was nonetheless the happiest of creatures, since all [her] desires were satisfied” (Ms A, 73v).

The inability of God to turn down our intercession when it is joined to reaching the limits of our littleness is a commonplace for the Little Flower and her Petal alike. Marcel says, “Prayer which is accompanied by moans of suffering is a prayer that God answers infallibly” (To the novices, 19 Feb 1950). We can see behind this claim two parallel components in Thérèse. First, she speaks of “thoughts of the soul that cannot be translated into language of the earth without losing their intimate and heavenly meaning” (Ms A, 35r). Second, she acknowledges that “God could not inspire in me unrealizable desires” (Ms C, 2v). So, if there is something ineffable in us, joined to us hitting against the outer reaches of our possibilities, well, God will do the rest that we desire.

The famous example here is the criminal Pranzini (Ms A, 45v–46v). Thérèse had heard of his case from the newspapers, and she prayed to God to change his heart and let him repent. Even to the last moment, he did not. Yet on the gallows, even after his final chance at last rites, he asked for a crucifix. This was enough for her to know that God had heard her prayers and granted her the impossible gift of a soul born into the next life for him.

Marcel has a similar tale of confidence (A 842–852; SH 32; Conv. 649–650). The man he prayed for was one Doctor LeRoy Desbarres, who had helped the Redemptorists but nonetheless remained committed to a non-Christian way of life and belief. The doctor was dying. Marcel offered his sacrifices like he had learned from his spiritual big sister. As with Pranzini, Desbarres did not change in this life. Yet Marcel did not believe what his confreres believed of their benefactor’s final end. He asked God that his own father would mend his ways and go to confession, and he proposed this as a sign that Desbarres would be saved at the last minute. Almost immediately, Marcel learned that his prayers had been answered before he made them.

Marcel, though, is a bit more of an active soul than Thérèse. He is a Redemptorist coadjutor brother. He’s not a Carmelite nun. As such, he is very conscious about joining his daily work to his prayers. That is a key emphasis that he brings to the Little Way. Now, Marcel is still little. He can’t do much. His work is always small. It’s housework. He does Nazareth work. He’s not got an external apostolate. Still, he joins his work to his prayer. Through it, he reaches his limits. And his limits reached, God must take over.

I’ve written quite a bit before on Marcel’s experiential theology of Nazareth. Suffice it to just give enough to tie this into the Little Way. Marcel is convinced that “all the merits we acquire, all the joy we feel, have their source in the perfect accomplishment of our daily work, since that is the proof that we conform in all things to the holy will of God” (To Father Alphonsus Tremblay, 31 Dec 1948). There’s no need to look down on this, for through this we do God’s will and then he can do ours:

One sees in it the wonderful results of laborious work, where one dirties one’s hands and feet. This type of work, considered as menial, is regarded by nearly everyone as without honour and very few are they who know how to appreciate it as being meritorious and infinitely pleasing to God. (OWN2.59–60)

The conversion, though, isn’t magic. It needs to join Martha to Mary, active life to contemplative life:

Although very busy with this manual work,

I never forget to join it to prayer.

Quite the contrary, all my fatigues,

I offer them to God as an ardent supplication. (OWN1.7)

Marcel’s logic is impeccable. In the first instance, “I believe that in doing the slightest thing for the love of God, he will reward me in giving himself to me” (OWN2.33). In the next instance, he knows that in having God, he has an unbounded power with him: “prayer which possesses equal strength to the infinite power of God” (OWN1.40). In Marcel’s view, prayer united to little tasks is how we commit ourselves to obedience and avoid big penances and mortifications, yet still remain useful to God. We only do what needs to be done, reach our limits, and give it all to God. This is enough suffering. It establishes everything God needs from a little soul:

He who wishes to become holy easily, has not to choose the things which do not please him. He has only to love God, giving witness to his love in looking to follow his will; that is where perfection exists. He who follows the will of God with all his heart is a saint. And even if in this conformity to the will of God he does not encounter sorrow, nor difficult things, nor suffering, he is, nevertheless, a saint. Holiness is found in God, and God conveys it to us, when we allow him to act freely with us.

Nevertheless, God does not forbid us to desire suffering, since suffering is a proof of love. It is not, however, necessary that our desire is excessive; it has to conform to God’s will. (To Brother Andrew, 22 Mar 1950)

Socks and peanuts

Just exactly how God’s will manifests itself is sometimes surprising. God applies himself to our lives with unpredictable gentleness.

Some of the most remarkable passages on a first reading of the Conversations are undoubtedly the long exchanges about the mortification of wearing socks (Conv. 475–499, 514, 688–689). Obviously, wearing socks is a healthy thing. If we say that putting them on and keeping them on is a mortification, that can come as a shock. Footwear is typically associated with mortification in the opposite direction. Saint Teresa’s discalced Carmelites, for example, forewent footwear for ascetic reasons. Here we have Marcel donning footwear, not eschewing it, for the same goal.

However good it may be for one’s health, especially when ill or inclined to sickness, wearing socks is something that Văn doesn’t much like. For one thing, it sets him apart from his confreres somewhat—and he does not appreciate that. “When I am very favoured externally,” says Marcel, “I then suffer a great deal interiorly” (Conv. 522). This is why wearing socks is spoken of exactly as a mortification. His confreres will see him as weak and needing good self-care. He doesn’t really like that. He’d rather be “normal.” He has to let that go. In letting it go, Jesus comes to him with great love: “the sight of your weakness makes you more lovable in my eyes than any gestures of love that you show me would be able to” (Conv. 529). But to get there required sacrifice—the sacrifice of appropriate self-care.

In the Little Way after abuse, sacrifices aren’t even always small good things foregone. They can also be certain good things accepted with humility. The Little Way becomes yet more little. Accepting to wear socks when there is a tendency to become ill is a form of obedience to the nature we are given. Similarly, taking care of oneself after abuse is a form of obedience to the situation we’ve been dealt.

We have, I think, moved a step further along from Thérèse. She was offering little sacrifices. She gave up a good thing here, a word she could offer for herself there. But Văn is sunk a little more in the mud than her again. He doesn’t just offer small sacrifices of good things. He also offers obedience to nature and situations that make him require more self-care. Acceptance of that weakness constitutes what we might call “the Little Way yet more little.”

Explaining to Marcel about the acceptability and indeed prudence of diminished sacrifices, Jesus says, “It is better to follow the will of the Church than one’s personal fervour” (Conv. 544). Indeed, this is an application of an even more general principle: “The best mortification is obedience” (Conv. 556). This enacts “a true prudence: the prudence of Love” (Conv. 544). If we take things too much on ourselves, it is possible that Jesus will say to us, as he does to Marcel, “Little brother, I spurn this sacrifice” (Conv. 556). This is not to deny that there is value in saints “making retribution for the excesses committed by men, by their self-denial” (Conv. 558–559). That remains true. It remains an act of love, when offered properly. Yet what Jesus wants instead of someone like Văn is simple: “accept all the little inconveniences that I send you and, by that, you will please me more than if you fasted for a thousand years” (Conv. 558). Among these, inconveniences that come from others take first place. Jesus asks Marcel to “bear a little interior suffering from your brethren” because that “is the best mortification” (Conv. 566). Sometimes the beneficiaries of these small sacrifices are specified, as when Jesus says that he allows Marcel to put up with a bit of gossip or false judgment so as “to avoid the sadness which comes to me from priests” (Conv. 687). In any case, obedience to the situation makes apparent what we are asked for. If the situation is uncomfortable, we endure it and accept it as a little sacrifice. If we offer it up and genuinely experience the interior suffering, that goes a long way.

It’s noteworthy that Marcel and Jesus aren’t naturally on the same page here. In these discourses, Jesus speaks some strong words, especially the ones that come close to that scolding that Marcel wants desperately to avoid, but every time they are offered with a greatly compassionate love that is almost palpable when reading them, even though decades later and in translation.

In the immediate context for comments on the will of the Church, Jesus is explaining as regards children. It doesn’t help children to fast or take on other penances. But the same evidently applies to Marcel, for obedience and the simplicity of the rules that apply to us amounts to the same thing. Perhaps we can say that, just as the France–Vietnam relationship is an analogue for the cleric–laity one (cf. Part 7), children are an analogue, particularly for Văn whose only time before clerical abuse was as a child, for those wounded by abuse, especially clerical abuse (cf. Part 4). Of course, Marcel really has a vocation to France, and he really has a vocation to children (as is evident, for example, in his concern for children who die without baptism: cf. Conv. 699–703). But these realities also signify or symbolize something else. It just doesn’t help children to go beyond the limits, or rarely. What is more beneficial is to sit with their state of weakness and take it to Jesus as it is, rather than pretend to be strong and break more spiritual bones in the process. Likewise for abuse survivors.

Perhaps one of the signs that this littlest version of the Little Way is the right one is an interior disposition like Văn’s: “Marcel, it is only through the force of argument that one manages to pamper you,” says Jesus with a laugh (Conv. 560). This doesn’t of course mean that Văn would resist. As he announces, “If Jesus spoiled me as he did [Dina Bélanger], I would let him do as he pleased” (Conv. 561). But it does mean that Jesus won’t force the pampering on us. We might need convincing. If so, that’s a promising sign. But to actually be convinced is necessary also.

Marcel’s understanding of the experiential theology of socks is tested again with the experiential theology of peanuts. The little thing he’s asked for in this case is to let go of preconceptions that he really has no firm reason for. He is asked to “offer your cough as a sacrifice to Jesus” (Conv. 595), but at the same time, he a thinks that peanuts will exacerbate his cough. This troubles him because his spiritual director has given him some peanuts to eat. He doesn’t actually know that peanuts will bother him. So, this becomes a lesson in the value of obedience and the simplicity of sacrifice that is pleasing to God (Conv. 614–615). In the end, we don’t hear that Marcel’s cough got any worse. Presumably, if he had been confident in his knowledge, he could have simply told his spiritual director and been politely excused. But in the absence of that, there is trust. It’s small. But it’s real.

These kinds of small sacrifices take on different forms. I’ll quote just a couple. The first is that being worried or troubled is itself considered as a sacrifice. Since little souls end up in such a state easily enough, that’s great news! This can be offered as a sacrifice, and maybe as a bonus it will then be removed from us:

Each time that you are troubled, even if only for the span of a breath, say this: “Little Jesus, I offer you this worry as a sacrifice.” Then, remain in peace. Thanks to this sacrifice, you will be consumed in the fire of Love, which will act freely in you. Thanks to this sacrifice, how many sinful souls will be able to avoid an occasion of sin that would expose them to falling into despair? (Conv. 595)

Marcel also makes a virtue of necessity. He doesn’t get to communicate as he’d like with a friend:

Out of time, out of paper, but not out of words, I am stopping here, sacrificing, in order to offer them to Jesus, the additional words that I would wish to write to you. (To Brother Andrew, 1 Apr 1948)

This is really obedience to circumstances and nature. He can’t have it any other way. Well, make a sacrifice of it! That’s as small as a sacrifice gets. But it’s the kind that Jesus has taught Marcel to offer. It’s the Little Way yet more little. It’s the Little Way for souls even more little.

“Little Jesus, I love you in the fly”

Marcel is an example of a soul that is contemplative—knowing and loving of God—but not so good at piece-by-piece meditation. I think this is a particular version of weakness or littleness that he shows us, too.

That Văn should not understand how to meditate during the initial period of contact with the Redemptorists is not surprising (cf. A 724; To Antonio Boucher, Mar 1944). But it is a bit remarkable that, after his entire novitiate year and after his first profession he should say the same thing: “I do not at all know how to meditate” (Conv. 725). There is something in him that just blocks it, apparently. Or perhaps, from one point of view, there is a block, whereas in a higher perspective, there is a grace leaping past the fundamentals to the goal. The only point to meditation on the mysteries of Jesus is to lead us to love them and rest in them with a contemplative gaze. If we’re already there because of familiarity coupled to weakness, then so be it!

The way that Marcel himself likes to leap to the end is to just tell Jesus that we love him in whatever it happens to be we are experiencing at the moment:

I remember one day when I had absolutely nothing to say to little Jesus, I kept looking at him, full of disgust, trying to meditate but without knowing how to begin. Seeing me in this state, little Jesus called me in order to teach me a way to occupy my mind with him. He told me first of all to look at the bench and he added: “Little brother, say: ‘I love you in this bench.’” He then told me to look at everything in the oratory and to repeat for each object: “Jesus, I love you in… the dust, in the fly, in the window, in the foot of the bench, in the flower, in the plant, in the flower pot, in the earth in the pot, in the shelf where it is placed, in the brick, in the pillar; I love you in the bird, in the bird’s song, in the frog, in the white tree frog, in the noise it makes, in the aeroplane, in the motor car… etc.” While little Jesus was teaching me this lesson, I felt like laughing and I was very distracted. I then had the following distraction: I said to myself that if it was my job to teach children, I would do such and such a thing to indulge them. Then little Jesus, once more, invited me to say: “Little Jesus, I love you in my little brothers who are playing.” Finally, little Jesus said to me: “Little Brother, you can always make use of this method and, so, you will be able, while resting, to make this prayer continually. In addition, this method will help you never to commit any fault in your distractions. Where the spirit leads you, your love also leads you, in such a way that I am loved by you in every place.”

Since then, when I have nothing to say, I use this method, but I often want to laugh. I once said: “Little Jesus, I love you in the fly.” And he said to me, laughing: “This fly smells terrible. It is very dirty, nevertheless you love me truly, in it. In comforting me like this, in very ordinary things, even in a simple grain of sand, you force me to follow you step by step in order to give you my kisses…” (Conv. 535–536)

This technique of prayer, which is hardly so much a technique as a relationship of simplicity ready to just chatter to Jesus about whatever it is that matters to us in the moment, sticks with Marcel. A few months later he proposes it to his sister:

For example, if I see an aeroplane flying by, I speak to him of it, telling him how I find this plane. Even at the time of meditation I speak to him of the smallest things of my daily life. Nevertheless, it seems that my heavenly Father is happy to see me act in this way. (To Tế, 15 Aug 1946)

Perhaps this is a version of the truth Marcel speaks about the simplicity of children and that of adults: “children’s simplicity is always natural, while that of adults can sometimes be natural and sometimes not” (Conv. 567). Weak, little souls need to be simple with their Father in Heaven. This goes for prayer just as much as it does for confidence, obedience, and sacrifice.

Spider’s webs

Ultimately, Marcel is also little and weak because he can’t fix everything within himself by himself. Not even his director of conscience can do that. Jesus tells Marcel that his spiritual director

has not succeeded in ridding you of anxieties. This spider’s web is very difficult to remove, but I have the firm hope that one day you will be relieved of it. I know that this spider’s web, in which consist your troubles, makes breathing very difficult for you. However, remain at peace, I am going to do the chores for you and so you will be very happy. (Conv. 591–592)

This image is memorable not only because of the irony that Thérèse was deathly afraid of spiders (cf. CJ 14.7.18, 18.8.7), whereas Marcel has the flexibility of both writing a poem with a spider as a protagonist (OWP20) and here using spider’s webs as a symbol of something unwanted. It’s also remarkable for what it tells us about the Little Way in post-abuse life, even post-trauma life.

The analogies are pretty clear. The room is Marcel’s soul. The chores stand for the work to be done on the soul, including that of tidying up “the after-effects of the sickness of my soul” (A 533)—everything that he endures in trauma (Part 4) and moral injury (Part 5, Part 6) after the clerical abuse (Part 1). The spider’s web is an example of something out of reach, both for Marcel and a spiritual companion. Given this difficulty, what Jesus promises is similar to the elevator. Jesus’ arms will do the work. In this case, he will clean up.

Applied to Marcel’s own circumstances, this is an idea from Thérèse. The Little Flower is insistent that Jesus is her director (Ms A, 48v, 70r, 71r), that we have no guide but Jesus (Ms A, 71r, 74r, 80v), indeed that Jesus is “the Director of directors,” the “Doctor of doctors,” and the one who reveals knowledge to the little ones (Ms A, 71r, 83v), and that many souls will be surprised at the ways God led her soul (Ms A, 70r).

Cleaning up the spider webs is exactly what a Theresian Jesus would do. The thing that makes Marcel unique here—or at least a development on top of Thérèse—is the long-lasting aftereffects of these spiders. He needs healing. He’s a survivor. Jesus knows to treat him gently. He also knows to accept his sacrifices, including the sacrifice of obedience to the natural need for self-care. Ultimately, as the Director of directors and Doctor of doctors, he knows when and how to clean up the debris and choking webs left behind by people who passed through and disrespected the house of God, “the living temple that I was,” that each of us is (A 158).

This is the Little Way. It’s smaller than the Little Way, but it too is the Little Way.

[1] Charles Bolduc, Frère Marcel Van (1928-1959). Un familier de Thérèse de Lisieux (Montreal/Paris: Éditions Paulines & Médiaspaul, 1986), 113–114.

[2] To = Marcel Van, Correspondence, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 3; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018).

[3] Conv. = Marcel Van, Conversations, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 2; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2017).

[4] A = Marcel Van, Autobiography, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 1; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2019).

[5] OW = Marcel Van, Other Writings, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 4; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018). Additional system for abbreviations explained on page 14, e.g., OWN = notebooks; OWV = various writings.

[6] All references to Saint Thérèse of Lisieux using the system in Œuvres complètes (Paris: Cerf / Desclée de Brouwer, 2023), with translations my own.

[7] Thérèse de Lisieux, Œuvres complètes (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 2023), 45.

[8] SH = Father Antonio Boucher, Short History of Van (Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2017). References to section number, not page number.