[ Marcel Văn and Clerical Abuse | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 ]

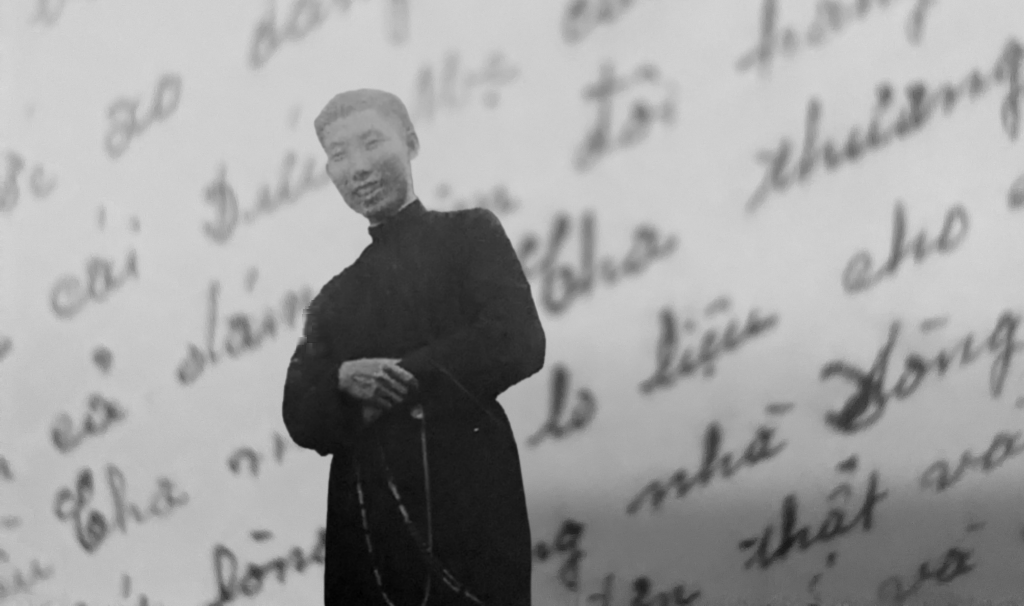

Continuing where the previous post left off, I will look at Marcel Văn’s intercession, not this time for priests, but for abuse victims and survivors. Marcel doesn’t deny the need to pray for priests; he thinks this is a vitally necessary action to take domination and clericalism out of the relationship between clerics and laity, to realize the truth about past harms, and to prevent future abuses. But he isn’t stuck on a global solution. He understands the immediate, local needs of the victims. He’s one himself.

Marcel doesn’t need any convincing or reminding to care for victims and survivors, so there is little exposition and theoretical ground to cover here. I will give some concrete examples of his intercession for abuse survivors.

Intercession during his lifetime

There is no surer way to know whether someone really cares than to watch their actions. Of course, lack of action doesn’t necessarily mean someone has no concern. There can always be impeding circumstances, whether social or personal. But where you do find action, you can be sure of concern. Marcel demonstrates such concern for abuse survivors. When a matter comes to his attention that it is within his power to help, he does what he can.

While still alive here-below Văn tried to get other people out of situations of abuse. One thinks first of how much he didn’t take things lying down when he was at Hữu Bằng. He rebelled. He converted rebellion into resistance. He just didn’t accept that he and his young companions were being treated like this. He wouldn’t let it stand, and he tried to make changes then and there. I talked a length about this kind of action in Part 3.

Marcel’s action for abuse victims and survivors, though, goes beyond this. He also acts as a guarantor and intercessor for survivors, trying to ameliorate their lives and opening up for them options for their present and their future. This doesn’t mean just prayer. It means concrete actions and possibilities that he attempts to set up. Granted, we don’t have a lot of evidence for this kind of tangible intercession from Marcel. But we have some. And I think that the fact that there is any is remarkable enough. Marcel became a coadjutor brother. He took a vow of poverty. For some periods of time, he had limited correspondence. Within the community, he didn’t even have the decision-making power of a priest. Yet, despite these limitations, there is evidence. We know though his capacities are limited, he tries to change material conditions for survivors he aware of.

When his friend Nghi’s younger brother Bái was still caught in a culture of abuse at that presbytery, Marcel made every effort to help. He spoke to the master of novices at his Hanoi Redemptorist community, i.e., he interceded. He obtained permission. He sent an envoy, so that “if it were possible to get Bái to the Hanoi community, he would enable him to study at the juniorate at Hanoi.” Sadly, Bái seems to have run away and could not at that time be found. So, having failed to obtain an immediate material result by his own exhausted efforts, Marcel interceded again—with Jesus: “So, I am confiding all of this business to Jesus, with the certainty that he can refuse me nothing” (To Nghi, 11 Jan 1948).[1]

Note how Marcel does everything he can. He intercedes in this world, then when everything falls through, he intercedes with heaven. He doesn’t leave it all up to Jesus from the get-go. Instead, he says he must do what is within his power. He must really care. It turns out, though, that Marcel’s proposed concrete change is impossible, for the survivor can no longer be found. It’s up to Jesus.

Some time passes. No news of Bái yet materializes. During this period, Marcel feels very impatient but has to wait and just resign himself to lack of news; this saddens him; still, he continues to pray, entreating the Blessed Virgin (To Nghi, 19 Apr 1949; To Nghi, 3 May 1949). Eventually, he seems on the verge of succeeding in getting Bái to Hanoi and thereafter sets about making sure of his lodgings and interceding for more funds for him (To Nghi, 9 Nov 1949). Unfortunately, the next year he is still deeply troubled that the whereabouts of Bái remain unknown (To Father Antonio Boucher, 22 Aug 1950). He has, however, gone all out. It is with Jesus now.

A similar story can be garnered from Marcel’s account, written for his spiritual director, of a journey made to his hometown to retrieve his younger sister and bring her back to Hanoi to attend a school. Once he arrives in Ngăm Giáo, the parish priest invites him over for conversation and dinner. This familiarizes the young Redemptorist brother once again with the situation of young aspirants to the priesthood who have taken up residence at a presbytery—one of the abusive situations of Văn’s past (cf. Part 1).

At Ngăm Giáo, Marcel’s reactions and actions tell a story of his concern for abuse victims and survivors. He writes, “I was then invaded by a feeling of sadness on observing that, in spite of the changes which had arisen in the country, in the presbytery nothing had changed, the strongest still controlled the weakest” (OWV 903–904).[2] Not content with an emotional response alone, he alleviates the work required of the young aspirants on his behalf, making sure that they do not do any menial labour for him (OWV 906–907). There is not much more he can do without creating too much upset, but the gentle efforts he makes are in fact accepted by the parish priest and any superiors. Perhaps it does not enact immediate change, but it throws a small spanner into the complicated machine. Meanwhile, Marcel, having done the most that he can, turns matters over to Jesus:

I still hope that later the little pupils in the presbytery will be liberated from this unjustified servitude. But, alas! Who will liberate then them? I am putting my hope in Jesus alone. Yes, I hope that Jesus himself will free these little ones of this yoke which weighs on them. I hope, what is more, I am certain that my hope will be realised. I am going to ask this favour for as long as it is not granted to me. (OWV 905)

We might also learn something from Văn’s devotion to the souls in purgatory. To be sure, the situation of a soul in purgatory differs quite a bit from a soul in the tormenting aftereffects of abuse. But Marcel’s attitude in the one case can inform our understanding of the other:

If I compare my lot to that of the souls kept in purgatory, I see very little difference. Also, to better understand their suffering, I have only to consider the days of aridity, that I live myself to have some idea.

The more I understand the lot of the souls in purgatory, the more I feel myself compelled strongly to come to their aid. I do so by offering little actions, as so many petals of flowers, which rejoice the heart of God, or as so many drops of dew, which will alleviate the heat which torments souls, for the glory of God in the Church militant. That is the teaching of my sister Thérèse, that I usually put into practice in silence. (OWN9.19–20)

Thus, we see that Marcel’s identification with the souls in purgatory is what draws himself to them, to intercede, and to offer little sacrifices à la sainte Thérèse. How much more does Marcel understand abuse victims and survivors! Surely he will intercede for them as well, if he is consistent. And we have observed that he does—first for his friend Bái, then for the little ones he meets in his hometown of Ngăm Giáo.

From all this, we can be sure of Văn’s concern. It is clear that, if he interceded for priests while on this earth, he did likewise for abuse victims and survivors—in a much more physical, tangible way in this case. There is less written about this by Marcel. But is that really surprising? As we saw in Part 7, Marcel needed a lot of reminding about praying for priests. The readiness that he demonstrates to help Bái and the aspirants at Ngăm Giáo is completely the opposite. He needs no prompting. He requires no reminder. Bequeathing a special mission would be unnecessary. He’s already and everywhere ready to put into practice intercession for abuse victims and survivors.

Intercession for abuse survivors of all kinds

Văn’s concern, though, isn’t limited to what he could do while he himself remained in this world, nor to survivors of clerical abuse alone. He intercedes—at least, we believe if we believe that he is among the Communion of Saints—for people now, and he is concerned about survivors of other kinds of abuse, too.

One of the most striking testimonies that I’ve heard in this regard can be found in the 2009 film Marcel Van, Hidden Apostle of Love, by Vu Dinh Khôi. This film is in French, but there is a version on YouTube that has English subtitles, thanks to the translation of Văn’s complete works himself, Jack Keogan. Just before five minutes into the film, there is a boy who narrates his own story:

I was born in Thailand. My mom in Thailand, she placed me in an orphanage. But I looked at the sky, I thought of my mom. It was like a kind of prayer, but I didn’t realize it. I tried to run away from the orphanage several times to go find my mom.

Then I was accepted into a family, but things didn’t go well. I was beaten. After that, I changed families. I was really adopted by these parents.

I got to know Marcel Van at my parents’. I met him thanks to a BD [bande dessinée, a general term for comics of any kind, including comic strips, comic books, and manga]. This was when I was small, when I was six years old, and it struck me and stuck with me. He had been beaten a lot, and I’d experienced that, too. Well, and things like that. So, after that, I wanted to know more about Van.

In my room, I made a prayer corner. The first image that I put in it was the photo of Van. And since he made me come to know Jesus, I also put an image of Jesus.

I really like serving [at the Mass]. When I am at the altar, I think of him, and that helps me a lot.

Van can help everyone. He can help young people, children, anyone who is sad.[3]

I think we can pick up quite a bit from this short declaration of the work of Văn in this boy’s life.

Văn appeals to someone who, despite not being a Christian, is attracted to his life and message. If you think about that, it’s pretty remarkable. Văn’s story is an extraordinary one, but it is definitely a Christian one. Yet it has the power to attract other hurting people as well. It can bring them comfort, strength, and a sense of being understood.

Văn appears as someone who evangelizes. Once the boy becomes his friend, he brings the boy to Jesus. He introduces one friend to another. This is just the diffusive, spreading capacity of love—no hint of proselytism.

All this happens because of Văn’s story. The boy meets him in an illustrated narrative of some sort. Of course, behind the scenes, we know that things are working the other way, too. The boy says that Văn can help everyone. He intercedes. He has eyes for us. It’s not a one-way street.

Something personal

If you have found this series on Marcel Văn and clerical abuse to be insightful, there is a chance that you have asked yourself why. I can tell you that, if anything profitable has emerged here, it’s not because of any professional background in psychology or theology. It’s simply what Thomas Aquinas would call knowledge by connaturality—understanding because it’s familiarized to you as second nature, because it’s filtered into your bones.

That’s not to say I know all the same kinds of clerical abuse as Văn. I don’t. I’ve been spared the worst, and as an adult convert, I certainly was spared the experience of clerical abuse of any kind in childhood. But I also expect that the majority who have lived their life in the Western world have no idea of just how much of a torture chamber is possible in the hands of priests when the developments of non-Christian secularism aren’t there to prevent the commission of certain crimes in broad daylight and with total impunity.

My experience of abuse, though, isn’t the point. This is not and never will be an autobiographical blog.

The point is the intercession of Văn. He took good care of me. His writings taught me in the year before I’d need to know him. Immediately before it all started to fall apart and the prison doors came clanking shut, I got a strong reminder of the love of Jesus in exactly the way I needed to hold onto—or rather be held—for the next months. It happened in a chapel of Our Lady of Perpetual Help at a seminary-like location on a date that I can’t remember exactly, but which was definitely in October 2013—which basically, but without my awareness at the time, echoed the conditions of the October 1941 grace Văn received (A 460–464).[4] These and so many other little details are enough to convince me that Văn has been looking after me. He’s sly about it. But he’s not as hidden as he’d like! I’m onto him.

How could it not be Văn? Evidently, I didn’t pray for the particular helps I received. I didn’t know to read Marcel because I’d become like him in many ways. Even a month before things got bad, I didn’t know I’d need that strength of purpose I got in that chapel. I didn’t yet know that I would need it. It’s all a mystery. It was preemptive. It fortified right before battle. But obviously, if I connect all the dots and many more besides together, I’m convinced Văn has been at my side. I really dislike focusing attention on myself, but I also can’t leave this unsaid. My suggestion of taking Marcel as an intercessor for abuse victims and survivors is a lot less credible if I don’t at least cough up to the smallest drop of my own testimony. May it please God that that’s all I need to give to assure you of my sincerity and that I can remain hidden enough.

Confidence

I think the only way to end an article on Marcel Văn’s intercession for abuse victims and survivors is to confide you, whoever you are and whatever your troubles may be, whether about abuse or not, to Văn. Confidence is his attitude towards God. Have confidence towards the infinite compassion and mercy of God and towards Văn.

Marcel, like his spiritual big sister, wanted to spend his heaven doing good on earth (CJ 17.7).[5] In the Conversations, it is said that he will have a similar mission to Thérèse, supporting souls on earth to know and spread God’s love (Conv. 251–252-1, 253).[6] In a notebook, he wrote, “My death will be life for a great number of souls” (OWN2.54). Marcel’s concluding words in the Autobiography paint a story of who he wants to be now and in the next life:

And now here is the last word that I am leaving to the souls of whom you are the representative, as the Blessed Virgin stands near her son Jesus in his agony: I leave to them my love; with this love, small as it is, I hope to satisfy the souls who wish to make themselves very small to come to Jesus. That is something I would wish to describe but, with my little talent, I do not have the words to do so… (A 882)

I can only say: Get to know Văn. Talk to him. He loves little souls. He understands. He will take care of you. He is, in my estimation, the greatest saint of postmodern times.

[1] To = Marcel Van, Correspondence, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 3; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018).

[2] OW = Marcel Van, Other Writings, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 4; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2018). Additional system for abbreviations explained on page 14, e.g., OWN = notebooks; OWV = various writings.

[3] My own translation from the French.

[4] A = Marcel Van, Autobiography, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 1; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2019).

[5] All references to Saint Thérèse of Lisieux using the system in Œuvres complètes (Paris: Cerf / Desclée de Brouwer, 2023), with translations my own.

[6] Conv. = Marcel Van, Conversations, trans. Jack Keogan (Complete Works 2; Versailles: Amis de Van Éditions, 2017).