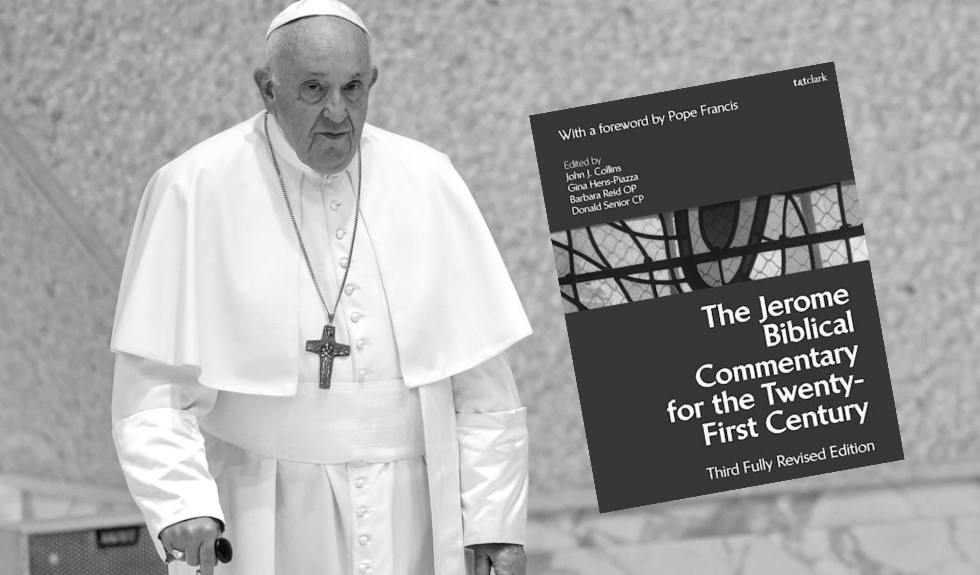

I’ve mentioned before that I often make use of the Jerome Biblical Commentary for the Twenty-First Century (a mouthful of a title for a book if ever there were one). What I haven’t said is that part of the reason I buckled down and purchased it was the foreword it boasts by Pope Francis. Now, that’s not to say I bought a book as expensive as this only for its foreword. That would be absurd. I had the older, New Jerome Biblical Commentary, so I knew the pedigree. I wanted an up-to-date Bible commentary that had some useful discussion. The factors stacked up.

In his two-page foreword[1] the Holy Father runs through a variety of issues. Starting with the Road to Emmaus and the opening of the Scriptures in light of the Risen Christ, Pope Francis moves through initiatives of local churches to make the Bible more accessible in our time, to the teachings of Vatican II, to the existential need to pray the Scriptures together with our Jewish brothers and sisters and our non-Catholic Christian brothers and sisters. He then gives a little exegesis on the importance of the written word of God in the aftermath of the exile of the Jewish people in the Old Testament. The final paragraph then turns to the mission of biblical scholarship. It helps a lot. It leads us, says the pope, to “serious study, deep love, and openness to the beauty and power of the Scriptures.”[2]

What happens next caught me off-guard—me, someone who has dedicated immense time and resources to identifying, connecting together, and illuminating the teaching of Pope Francis on Christian contemplative prayer. Yet it caught me off-guard anyway. The Holy Father says that he spoke about this already in his exhortation The Joy of the Gospel:

The best incentive for sharing the Gospel comes from contemplating it with love, lingering over its pages and reading it with the heart. If we approach it in this way, its beauty will amaze and constantly excite us. But if this is to come about, we need to recover a contemplative spirit which can help us to realize ever anew that we have been entrusted with a treasure which makes us more human and helps us to lead a new life. There is nothing more precious which we can give to others (Evangelii Gaudium 264).[3]

This is a direct quote from the apostolic exhortation. It is also how the foreword ends. There isn’t a single word after this. That’s it. Pope Francis talks about the character of the Bible and the People of God reading it. Then, he ends with an appeal to the spirit of contemplation.

And that short little quote says a lot. Note the connection between beauty and contemplation that is characteristic of Pope Francis. Note the need for love to be combined with knowledge, here book knowledge, to add up to an experience of beauty, here beauty of God and thus contemplation—also characteristic of Pope Francis. Note the idea of being entrusted or gifted with something to contemplate—again characteristic of Pope Francis. Finally, of course, there is the connection between contemplation and resulting action—which is characteristic too of Pope Francis.

I’ve found all these things in Pope Francis before. It took a foreword to a biblical commentary for me to realize that he had sown the seeds for it all in one of his first papal teaching documents a decade ago.

Even when you already know his game, he’s full of surprises.

Kind of like his Father upstairs.

[1] Pope Francis, “Foreword,” in John J. Collins, Gina Hens-Piazza, Barabara Reid, and Donald Senior (eds.), The Jerome Biblical Commentary for the Twenty-First Century, third fully revised edition (London: T&T Clark, 2020), vii–viii.

[2] Ibid., viii.

[3] Ibid.