Love isn’t a mental phenomenon. It involves the whole person. That’s what most people believe. Fortunately, too, it’s what Christianity teaches, and the great advantage in credibility here is the fact that God became human, and then, to do one better, descended on other humans to knit them into a great body. The fire of the Holy Spirit is grace, and grace brings divine light.

This participation in illumination allows the being to become what it ought to be. There is a transfiguration of the entire being, intelligence, body, sensitive nature. The flesh itself, the human being in its corporality, in its senses, is wholly recreated by charity. Charity has to pass all the way to our fingertips. If that doesn’t happen, something is awry![1]

The book that I’ve just quoted from, by Marie-Joseph Le Guillou, is one devoted to this “theme that we have forgotten too much.”[2] Love changes us down to our fingertips. The parts of our body, our features, and our comportment that alter depend greatly on the individual person. The time that it takes is a great mystery. Everything is in the hands of God—except for when we take it away. But still, “transfiguration” happens.

Over the years, I’ve pointed out some astounding examples of this, and perhaps the favourite of Father Le Guillou himself was Charles de Foucauld. Whereas Thérèse seems transfigured on one side of her face, but not yet the other, Brother Charles of Jesus seems to be done over altogether.[3] In fact, you can point out—as an Eastern Christian did to Le Guillou, and as Le Guillou ends his wonderful book recounting—that when it comes to Charles de Foucauld, “this face is an icon.”[4]

One transfiguration that I’ve never drawn attention to is that of one of the most astounding followers and interpreters, if not the most astounding follower and interpreter, of Charles de Foucauld himself: Little Sister Magdeleine of Jesus, founder of the Little Sisters of Jesus.

Something about her face

Many of the testimonies about how love had taken hold of Little Sister Magdeleine’s body rest on the features of her face.

For example, in the mid-1950s she was being guided around the site at Tre Fontane that was being donated by the Trappists for use as a house in Rome for the Little Sisters. The Trappist brother who was guiding her remarked on the fact that she seemed to live in a spiritual atmosphere of Providence, as if all that was happening in her life, no matter how off-the-wall and original, was just normal. He also could not forget her gaze: “He had been struck, too, by the fact that she looked as if she had suffered. Her face was thin, her look was penetrating and her features drawn.”[5] It was all part of “a poverty that was total.”[6]

That may be true. But with the Little Sisters, the ideal of poverty was always to be made subservient to the needs of love. It would do little to be properly poor, if we didn’t also organize everything for the sake of permeating realities first with loving presence.

Then again, the love that Madgeleine knew was the love of Jesus, and as much as she emphasized the Jesus of the manger, and the little Jesus in Mary’s arms, reaching out to the whole world, still Bethlehem had foreshadowing of Calvary. So did her love have suffering? Oh yes, of course.

While this Trappist monk was struck by poverty and suffering in her visage, the Orthodox Patriarch Athenagoras was drawn to another Christian virtue or value: “When I look at you, I find in your face the reflection of my own. We have the same desire for unity.”[7] Unquestionably, unity was dear to Little Sister Magdeleine. In the trial days, her order found its happiest home among the Congregation for Eastern Churches, rather than the usual Propaganda Fide. She tried out professing non-Catholic Christian sisters. The consecration of her entire effort to a special relationship with Muslim people was the starting point that never disappeared. Little Sisters were to go everywhere and be with everyone, particularly the excluded. What Athenagoras found in her face, too, was real.

The dimensions of her face seem to have attracted people who knew her a bit better, too. Athman, a Muslim man who had known her at her very first foundation at Sidi Boujnan in the North African desert, recounted how, when he knew her decades previously, “her face was never severe.”[8]

Just those eyes

While these people who knew her only briefly, or who saw her from outside in some way, due to their own religious adherence, spoke of her face, still others, many of whom knew her longer and from within the same perspective, had a much narrower focus. Little Sister Magdeleine’s face, rooted in her character, transformed by Christ, while remarkable, was more or less overtaken by one feature of it: her eyes.

For example, if we jump to the end of her life (1989):

Little Sister Magdeleine had a beautiful profile, but her sisters acknowledged that in life they had scarcely noticed it because of the striking quality of her eyes. In 1992 one who had been a Little Sister for eight years but who subsequently left and married, wrote of how Little Sister Magdeleine’s whole being was consumed with love and of how ‘Her face had become quite small but her eyes transmitted such a force of love which was no longer hers: Jesus was speaking through her.’[9]

Little Sister Magdeleine might have been beautiful, but it would do her a disservice to confine that beauty to a narrow consideration of physical features in themselves, as if life could be compartmentalized like that and still contain its vitality. Her beauty was primarily something other. At least, the beautiful attractiveness of her was something else. It was the beauty of the love of Christ. And that love shone through her eyes. It rose out of her otherwise beautiful face and made it into something new, radiating not a limited, physical beauty, but one that is knowledge of God and love of him.

This is a constant theme. Moving from her deathbed all the way back to her first foundation in North Africa (late 1930s), we have similar testimonies about her ability to communicate with her eyes:

Among the accounts of the many that would follow are frequent references rather to a certain look of which she was capable. The dark eyes that could communicate love to her Arab friends without resorting to words appeared also to be endowed with a capacity for penetration, even when her attention was diverted only fleetingly to an individual from a multitude of practical concerns. Memories of even those who were closest to her were imprecise as to the actual colour of her eyes ‘neither blue nor brown, hazel perhaps with green tints’. More memorable was the way in which they were transparent with goodness and with energy and when she smiled it was ‘as if they were lit by some inner light’. There was great depth in her look and it could, according to the circumstances, reflect joy, sorrow or concern, both hers and other people’s. The woman who spoke with fervour of the message of Charles de Foucauld and of her beloved Algerian friends manifestly had charisma.[10]

Her eyes “penetrate” and “communicate” love. The actual physical features are difficult to pin down. But they express human emotions, whether hers or others—as if her body were made for communion itself, for being part of that Body of Christ wherein if one member suffers, so do the others, and if one member rejoices, then so do the others (1 Cor 12:26). What Kathryn Spink, her biographer, calls “charisma” is hardly what that word means in normal, human terms. It’s charity, love, transfiguration of the whole person, from the point where grace enters, down to our fingertips—or eyelids.

Little Sister Magdeleine herself knew it. She testified to it:

She spoke little Arabic but she had a gift of communication which did not require many words. It was a gift of which she was aware: ‘I love them’, she once wrote, ‘and my eyes tell them so.’ Because of this love she could go off into the desert confident of her safety, knowing that the local people had already begun to see her as one of them and that even in her absence the process of construction would continue. It did not matter that she was Christian and they were Muslims. She wanted to live among Muslims as a witness of Christ’s love for all, but this did not detract in any way from her sincere regard for their commitment to their own religion.[11]

Not only did she know that she had this ability to communicate her love with her face—with her eyes. She knew that it was a manifestation of her particular way of loving in the world, not withdrawn like a contemplative of old, but immersed in the hustle and bustle of everyone else’s life, like the contemplatives she had an intuition for the birth of in the new world that was emerging. This was a feature of Christian contemplation, and it was one that she knew needed to instantiate and make real the implications of the Incarnation for people today. Love must become visible, down to our gestures, even our features as they are worn over, in time, by our repeated bodily comportment.

This ability to communicate with her eyes did not diminish with the years. Time did not strip her of it, even as time tends to weaken or remove certain physical abilities of us all:

In the last weeks of her life when she was able to speak only with difficulty it was remarkable to some how everything she could not actually say passed through her eyes.[12]

Giving and receiving

Little Sister Magdeleine, was, then, in a sense more literal than usual, a human realization of Jesus’ words: “The eye is the lamp of the body. So if your eye is healthy, your whole body will be full of light” (Mt 6:22 NRSV). But she was also a living witness to the words spoken right before that in the Sermon on the Mount: “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also” (Mt 6:21 NRSV). What others found in her, she too found in others.

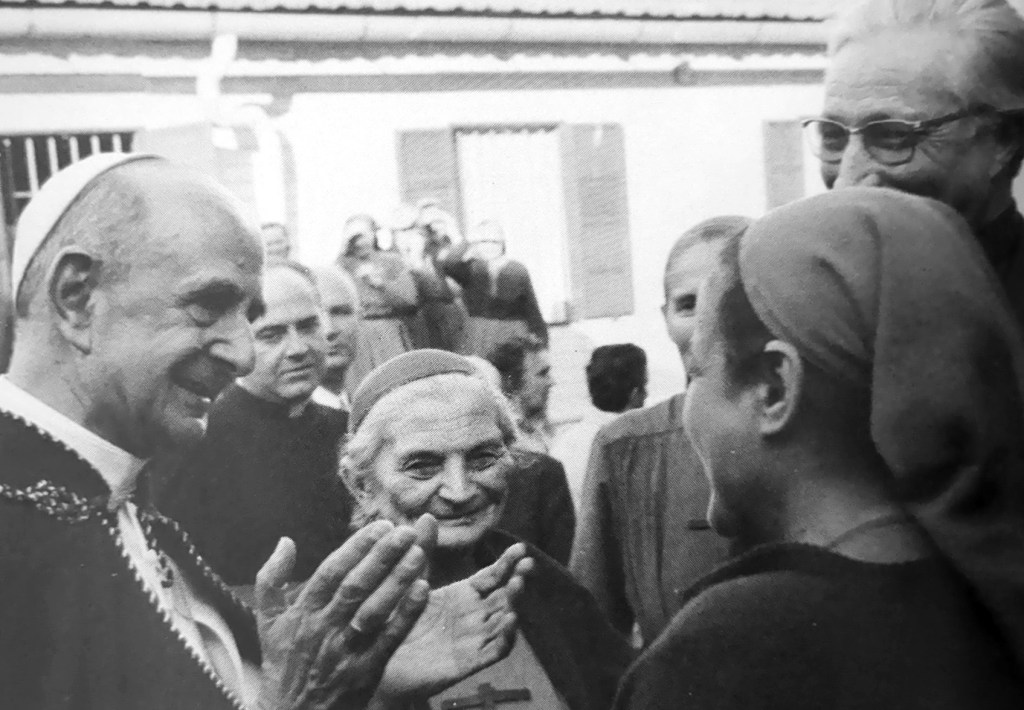

Little Sister Magdeleine had an astonishing, simple, clear relationship with Pope Pius XII.[13] In time, he came to know her business and kept close tabs, in an entirely paternal and friendly way, on her comings and goings, her foundations, her plans, her new ways. But even at the beginning, Little Sister Magdeleine detected something. And according to her, that something manifested itself in his eyes: “As she spoke the Pope smiled and looked at her with eyes which, she afterwards reported, made her feel at once accepted and understood.”[14] His eyes communicated acceptance and understanding to her. She received what she gave.

Not only in the positive register, but in the negative, the look of one’s eyes could preoccupy her. Criticism of her Sisters could focus on this point:

For her pride was the ultimate sin and one she would not tolerate under any circumstances. ‘Disdainful, proud eyes are painful to me,’ she once acknowledged, and in her determination to stamp out pride when she came across it in her sisters, she knew she could be excessively severe.[15]

She probably saw this, because it was a dimension of human existence that mattered to her, whether consciously and worked out in detail, or without detailed thought and intuitively. Something was either right or wrong. We either communicate contemplation—knowledge and love of God—with our demeanor, or we don’t. If we don’t, what is wrong? What needs to be placed more at the feet of the Spirit who will metamorphose us? What do we hold back, and whose intercession might we turn to for help?

As Marie-Joseph Le Guillou insisted: “Charity has to pass all the way to our fingertips”—and the well-worn lines of, and the light behind, our eyes. “If that doesn’t happen, something is awry!”[16]

[1] Marie-Joseph Le Guillou, Des êtres sont transfigurés. Pourquoi pas nous? (Paris: Parole et Silence, 2001), 17.

[2] Ibid., 18.

[3] Ibid., 26.

[4] Ibid., 164.

[5] Kathryn Spink, The Call of the Desert: A Biography of Little Sister Magdeleine of Jesus (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1993), 153.

[6] Ibid., 154.

[7] Ibid., 201.

[8] Ibid., 199.

[9] Ibid., 251.

[10] Ibid., 49.

[11] Ibid., 46.

[12] Ibid., 251.

[13] It was, surprisingly, under Saint John XXIII that the Little Sisters encountered their greatest ecclesiastical trials; the previous pope had followed them attentively, and Saints Paul VI and John Paul II were basically personal friends of Magdeleine even before their elections.

[14] Ibid., 69.

[15] Ibid., 144.

[16] Le Guillou, Des êtres sont transfigurés, 17.