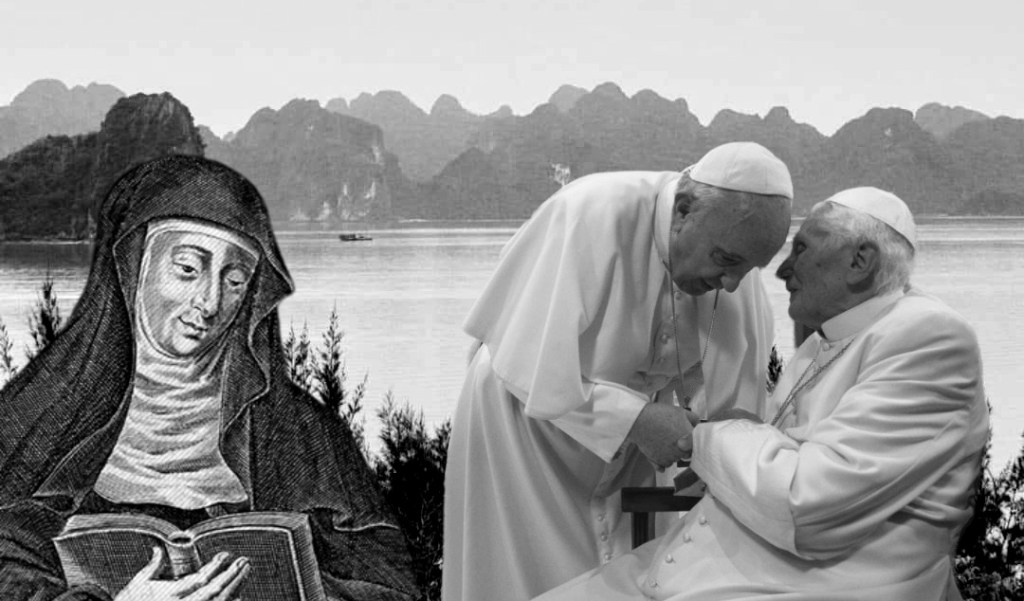

The feast of Saint Hildegard of Bingen is a new one for the universal Church. Only declared a saint by Pope Benedict XVI using the process of equivalent canonization at Pentecost 2012,[1] Hildegard was quickly declared a Doctor of the Church in October of the same year.[2] Her feast was left unpromulgated, however, until Pope Francis inscribed it in the General Roman Calendar in January 2021.[3] Her feast day remained steady on September 17, from what it had been as a blessed. It is only appropriate that her feast day be found in the month of September, after all. This is the Season of Creation, and Hildegard certainly had a lot to say about her beloved viriditas, green vigour.

In this short post, I’ll look at the relationships which both Popes Benedict and Francis have had to the saint.

Pope Benedict XVI

The former pope was, let’s say, a big fan. In fact, as he noted in his apostolic letter proclaiming Hildegard a Doctor of the Church, he was part of the team of bishops petitioning for her to be declared such as far back as the ’70s:

By virtue of her reputation for holiness and her eminent teaching, on 6 March 1979 Cardinal Joseph Höffner, Archbishop of Cologne and President of the German Bishops’ Conference, together with the Cardinals, Archbishops and Bishops of the same Conference, including myself as Cardinal Archbishop of Munich and Freising, submitted to Blessed John Paul II the request that Hildegard of Bingen be declared a Doctor of the Universal Church.[4]

Note that at this time, there were only two female Doctors of the Church (both declared such by Pope Saint Paul VI), Teresa of Avila and Catherine of Siena, and Hildegard had not even been recognized as a saint in the universal Church. Certainly, she was regarded as a saint locally and a blessed universally. But devotion to her as canonized had not spread to the entire world. Yet Joseph Ratzinger was asking, along with some fellow German bishops, for her to be declared by the newly elected pontiff, not just a saint, but a universal teaching saint. This is dedication. He was a fan.

In that same letter, Pope Benedict highlighted the place of created nature in Hildegard’s writings and teaching, which are situated within an integral grasp of everything the Church believes and teaches:

The texts she produced are refreshing in their authentic “intellectual charity” and emphasize the power of penetration and comprehensiveness of her contemplation of the mystery of the Blessed Trinity, the Incarnation, the Church, humanity and nature as God’s creation, to be appreciated and respected.[5]

He stressed that “[h]er message appears extraordinarily timely in today’s world, which is especially sensitive to the values that she proposed and lived,” in part because of “her sensitivity to nature, whose laws are to be safeguarded and not violated.”[6]

This is a reference to viriditas. A term frequent in the writings of Hildegard, viriditas is essentially the innate quality of nature to “green” itself, to grow from within, to generate and regenerate, within the limits of that nature itself. It is something to be respected, not overstepped. To overstep it results in damage. The vision hits a mark not too far from Francis of Assisi, but the way it gets there is less lyrical (though Hildegard can certainly be lyrical) and more conceptual and methodical. Acts of honouring viriditas include exercise of certain virtues, like justice, humility, gentleness, and temperance, and gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as knowledge, which inspires our relationships with created beings. Respect for this “green vigour” has a place in a contemplative and Christian life.

In short, Benedict found a lot to like in Hildegard of Bingen. He liked it early. He worked for it as cardinal, then as pope. One can probably attribute a lot of his concern for ecology—be it natural, human, or social—to this saint.

Pope Francis

For the current pope, Hildegard of Bingen is less of a significant figure, even though he is evidently very much concerned with some of her main messages.

One area in which Hildegard matters for Francis is the Church—and the sins of her ministers and members, as well as the reform of the Church itself. But here, in fact, the present pope is relying on his predecessor. As Pope Francis notes,

Benedict XVI, addressing the Curia on 20 December 2010 and drawing inspiration from a vision of Saint Hildegard of Bingen, recalled that the very face of the Church can be “stained with dust” and “her garment torn”. I too have noted that healing “comes about through an awareness of our sickness and of a personal and communal decision to be cured by patiently and perseveringly accepting the remedy” (Address to the Roman Curia, 22 December 2014).[7]

Likewise, he considers Hildegard an exceptional example of a woman of faith (Gaudete et Exsultate 17), mentioned first, alongside Saint Bridget, Saint Catherine of Siena, Saint Teresa of Avila, and Saint Thérèse of Lisieux. Our saint’s contribution, again, pertains to making the Church more of what she truly is and should be. The pope specifies her contribution to “new spiritual vigour and important reforms in the Church.” We can note a bit of a theme here. When he does refer to her, Pope Francis sees Hildegard more as a figure for reform of the Church, rather than “greening” it or focusing on her ideas about created nature.

That said, it is clear that what Hildegard cared for matters a lot to Pope Francis, even if she appears hardly at all in his papal writings. The need to protect and renew the environment—“our common home,” as the Holy Father calls it—has found great articulation in the encyclical letter Laudato Si’, the apostolic exhortation Querida Amazonia, and (I assume) the forthcoming apostolic exhortation that is a sequel to these documents, to be published at the close of this Season of Creation, the feast of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Pope Francis does not cite Hildegard’s notion of viriditas, or even allude to it, like his predecessor. But the reason for that is, I think, threefold. First, the more apparent influence for Francis is, well, Francis—of Assisi. Second, this medieval mystic is more well known and easily approachable than is Hildegard the medieval intellectual; people respond to him more readily. Third, viriditas itself is just an idea. Ideas are fine. Notions can focus us. But they can also be bypassed, when we have other ways to get to where we need to go. As such, the Holy Father prefers realities themselves. “Realities are more important than ideas” (Evangelii Gaudium 231–233)—a principle cited in Laudato Si’ (LS 110, 201).

Pope Francis prefers the leap to the mental scaffolding that facilitates it. If he communicates the substance without the words, the message without the ideas, that is just his way. He wants everyone to listen. No need to use the theological vocabulary from a thousand years ago—even if many people today are coming to appreciate the woman who gave it to us. We can shoot to the reality today in different ways. If that means speaking less about some of the great messengers of old, particularly the thinkers like Hildegard of Bingen, then that’s the way it is.

The messenger still matters, and to an extent, it’s hard to imagine that we’d be where we are in this Season of Creation, with the developing social teaching of the Church on our common home, without this wonderful contemplative Benedictine nun from medieval Germany, an inspiration to the “green pope” before Francis, Benedict XVI.

[1] Pope Benedict XVI, “Regina Caeli” (May 27, 2012), which can be read here.

[2] Pope Benedict XVI, apostolic letter “Proclaiming Saint Hildegard of Bingen, professed nun of the Order of Saint Benedict, a Doctor of the Universal Church” (October 7, 2012), which can be read here.

[3] Pope Francis, “Decree on the Inscription of the Celebrations of Saint Gregory of Narek, Abbot and Doctor of the Church, Saint John De Avila, Priest and Doctor of the Church and Saint Hildegard of Bingen, Virgin and Doctor of the Church, in the General Roman Calendar” (January 25, 2021), which can be read here.

[4] Pope Benedict XVI, apostolic letter “Proclaiming Saint Hildegard of Bingen, professed nun of the Order of Saint Benedict, a Doctor of the Universal Church,” art. cit., 7.

[5] Ibid., 3.

[6] Ibid., 7.

[7] Pope Francis, “Presentation of the Christmas Greetings to the Roman Curia” (December 22, 2016), fn 16, which can be read here.